Drama (11 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

As our plans fell into place, my mother nearly burst with pride. She saw the event as a radical social statement on my part, and it warmed the cockles of her lefty heart. When the evening arrived, I did my best to ignore the political baggage she had attached to it. The four of us gathered at the home of Art’s date and we ate supper together. The air was charged with nervous anxiety, but probably no more so than any of our classmates were feeling, in households all over town. We ate together in near-silence. The anarchic humor that Patty and I usually shared had disappeared. We were a perfectly typical quartet of shy, tentative teenagers heading to the prom.

But at the prom itself, we cut loose. The awkwardness of the early evening gave way to Patty’s usual high spirits. She revealed herself to be an electrifying dancer and I did my best to keep pace with her. At one point she kicked off her shoes and danced in her bare feet. A crowd gradually formed a circle around us and clapped in rhythm, urging us on. We were having a ball. As the two of us reached a fever pitch, I noticed Florence Burke elbowing her way into the circle. Miss Burke was the school’s assistant principal, a large, florid, middle-aged woman, full of sunny rectitude. Ordinarily she enforced school rules with her own brand of edgy good humor. But tonight she glowered. She brought Patty and me to a halt, declaring that dancing in bare feet was strictly prohibited at school dances. Patty was unfazed. She cheerfully put her shoes back on and we continued to dance, with only slightly less abandon. I barely gave it a thought when, in the last hour of the prom, I noticed several white girls dancing in bare feet.

When I walked into my homeroom on the following Monday morning, a letter was waiting for me. The letter was written in blue ink on pink stationery. It was short, to the point, and unsigned.

John,

You have desecrated the Junior Prom. We don’t want any nigger lovers at our school.

As I read the letter, my knees went weak. I was seized with a mix of shock, rage, and nausea. For the rest of that day, I stared balefully at the faces of my classmates in the halls and classrooms, suspecting every one of them of harboring secret poisonous prejudice. I was due to preside over an assembly that midday, and I spent the entire morning preparing to read the obscene letter out loud to the student population and declaim against hatred and racism. When the time came, my courage failed me and I conducted the assembly with sullen ill humor.

Instead of spewing my feelings in public, I unburdened myself to Henry Drewry, my revered African-American history teacher, in his office after school. I sat down at Mr. Drewry’s desk, handed him the letter, and watched him as he read it. The written words did not appear to surprise or distress him. He merely sighed with a kind of world-weary resignation. In the conversation that followed, he gave me the profound gift of his own experience of racism and instantly took his place in my pantheon of personal heroes. He said that he could list hundreds of examples of this kind of hatred and cowardice from his own experience, even within the leafy confines of liberal Princeton. He said that I was lucky to be made aware of this subterranean evil but that I should not allow it to turn me bitter or vengeful. He reassured me that I had been wise to stay mum on the subject in front of the gathered student body, but that I should find ways of judiciously fighting prejudice in my own life. Leaving his office, I felt that Henry Drewry, that amiable, mild-mannered man, was the strongest person I had ever met. The next day, I clung to his words when a car sped by as I walked home from school and a red-faced young bigot screeched out at me from the passenger-side window:

“Lithgow’s a nigger lover!”

But the Patty Brown episode was a dark moment in the midst of sunny times. For my entire family, things were looking up. That spring, my father was asked to put aside his high school hucksterism and take over as artistic director of the McCarter Theatre. This was far and away the most prestigious assignment he had ever been given. For the moment, he arranged to also continue as head of his summer Shakespeare festival in Cleveland, thus providing his core company of actors with year-round employment. The family packed up for another move to Ohio, but this time just for a summer gig. Dad hired me to work in the company as an apprentice and bit-part actor, and I embraced his nepotism with undiluted enthusiasm. It would be three months of exhausting work, but I also planned another project for my spare time. Typing, of all things, had been one casualty of my scattershot high school education. And so, armed with a graduation-gift used Remington and a how-to manual, I intended to teach myself to type. This was more a necessity than a whim: I’d been accepted to Harvard College on a full scholarship for the following fall.

O

ver the course of a freakishly hot month of May, I rang down the curtain on my grade school years. I marked all the sentimental rituals that bring high school to a close—Senior Prom, Commencement, and a series of desultory end-of-the-year parties. All through those weeks, I recall feeling an enormous sense of relief, as if I had reached the end of a marathon that I never thought I could complete. But the days were also suffused with a curious sensation of unease, if not guilt. I had made a great success of Princeton High School, but that success felt oddly similar to sneaking into a front-row seat during an intermission at McCarter Theatre. I couldn’t escape the sense that I had pulled the wool over everyone’s eyes, that I was leaving town just in time, before anyone found me out. All around me I saw classmates with a shared history, young adults who had lived their entire lives together, in the same small town. To them, saying goodbye at the end of high school was an agonizing rupture. Not to me. I had just been passing through, shuffling identities like a riverboat gambler. My genial self-assurance had been the performance of a lifetime. Although it never occurred to me at the time, the haphazard circumstances of my school years had prepared me, to an uncanny degree, for a life of acting.

Pinch Me

F

or someone with no intention of becoming an actor, things were getting pretty serious. In late June of 1963, days after my high school graduation, I arrived in the leafy confines of suburban Lakewood, Ohio, to join the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival for its second summer season. I was a bona fide member of a professional repertory company. My father had hired me as one of a team of five apprentices, with the usual long list of backstage duties, ranging from scene painting and prop making to mopping the stage. But along with all that drudgery, we five apprentices were expected to fill out the lower ranks of the acting company. All summer long I was going to

act

.

Like so many of my father’s early ventures, the festival took place in a bizarrely unlikely setting. The plays were mounted in the large, echoing auditorium of the Lakewood High School, twenty minutes from downtown Cleveland. At show time, theatergoers filed into the school building beneath an enormous polychrome sculpture of a blond, Nordic-looking young farmer, on his knees planting a sapling. Apparently the figure was originally intended to be Johnny Appleseed until some unsavory historical facts about Appleseed’s sex life had been uncovered by Lakewood’s prudish citizenry. Now the sculpture was simply called

The Early Settler

. This was the source of great amusement to the waggish New York actors who arrived at the start of the season. They decided that the Early Settler was actually Lemuel Gulliver, jerking off into the soil.

These were the years of the festival’s infancy, but it has survived to this day, nearly fifty years after my father launched it. Now known as the Great Lakes Theater Festival, it has long since expanded its repertory beyond the Shakespearean canon and has relocated to downtown Cleveland, where it is housed in the venerable Hanna Theatre (by coincidence, the site of Bert Lahr’s long-ago performance as Bottom the Weaver). Nowadays, the festival’s publicity materials tend to banner the names of two famous alumni. One is Tom Hanks, who played major roles in three seasons there early in his career. The other is John Lithgow, who was there for two seasons, several years earlier. No mention is ever made of how tiny his roles were.

But to me, size did not matter. I was giddy at the prospect of playing actual parts, no matter how small, in the summer’s entire repertory. On a large casting grid, my father had put my name down for roles in each of six plays. I was to be little more than a minor player—the roles averaged only about a dozen lines apiece. But each part was a big step up from spear carrier, and each character had a name. And though most of those names had only one syllable (the best parts were Nym, Froth, Pinch, and Le Fer), at least I would have a line to myself in every playbill. The following summer I would return to the festival and would take on larger roles with more syllables in their names (Hortensio, Guildenstern, Lucilius, Artemidorus), but for the moment, little monosyllabic parts suited me just fine.

The Comedy of Errors

was the first show that season. My father was set to direct it and I was to play the small but juicy role of Dr. Pinch. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, Dr. Pinch was by far my biggest challenge to date. On my first day, I put my head down and started to rehearse, blithely unaware of how carefully I was being scrutinized by the rest of the cast. Acting is a highly competitive game at every level, and if the boss’s son does not deliver the goods, the unspoken judgment of his onstage colleagues is instantaneous and withering. By the same token, a smashing Dr. Pinch would gain me acceptance from everyone for the rest of the summer. And as luck would have it, I was a smashing Dr. Pinch.

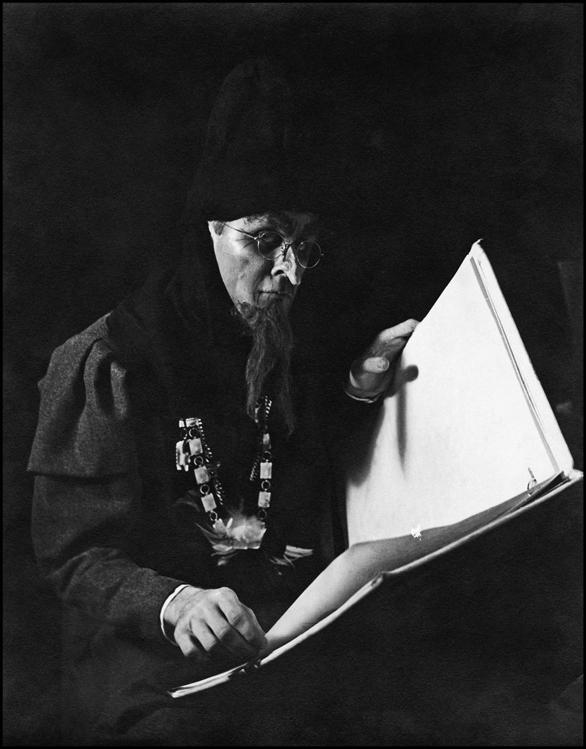

The play is Shakespeare’s most frivolous, his reworking of an ancient Roman farce by Plautus. The plot involves two sets of identical twins. One set are both named Antipholus and the other are their servants, both named Dromio. Each master-servant pair believes that the other was lost at sea. The fun begins when one Antipholus arrives in the other one’s city, accompanied by his rascally servant Dromio. Mistaken identities, cross-purposes, and romantic complications kick in and escalate. At the very height of the mayhem, Dr. Pinch has his one and only scene. He is a schoolmaster and mountebank conjuror, brought onstage to exorcize the demons that have supposedly possessed one of the mistaken Antipholi. It is a scene clearly calculated to be explosively over-the-top, and from day one of rehearsals, I set out to make a meal of it.

By that summer I was a few months shy of eighteen years old and thin as a rail. Although I towered over most of the company, I only weighed 175 pounds,

fifty pounds lighter

than I am today. As Dr. Pinch, I wore a form-fitting gray wool costume resembling the working clothes of a Victorian governess. Atop my head was a tall, sausage-shaped black hat with a flap covering my ears and the nape of my neck. For every performance I sculpted a pointy putty nose, I glued wispy strands of gray crepe hair to my eyebrows and chin, I sported round wire-rimmed glasses, and I painted my face with yellowish greasepaint and spidery wrinkles. I looked like a distant cousin of the Wicked Witch of the West, a pencil with jaundice. With my father’s prodding, I devised all sorts of frenetic comic business involving an outsized book of spells, magic potions in little bottles, and a bag of confetti, which I tossed around like fairy dust. The tech crew even concealed a flash pot on the stage so that when I screeched out my final, climactic imprecations, they were accompanied by an explosion and a six-foot-high mushroom cloud. All of this nonsense was greeted with gales of crippling laughter, and every night, when I skittered off stage, I heard the glorious sound of exit applause at my back.

I couldn’t see into the future, of course, so I had no way of knowing. But looking back, it is perfectly obvious: in that first show of the summer I had created the precursor to Dr. Emilio Lizardo in

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai

, far and away my most outrageous screen performance, and, secretly, one of my favorites.

In a larger sense, that summer I was creating a template for the wildly varied range of roles that would unfold over the next several decades in my checkerboard acting career. Every actor weaned on Shakespeare inevitably emerges as a character actor. Shakespeare’s plays shift briskly from one genre to the next. In

Hamlet

, when Polonius speaks of the arrival of traveling players and of the plays they perform—“tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral . . . tragical-comical-historical-pastoral”—he could be describing Shakespeare’s own output. Hence an actor in a Shakespearean troupe becomes accustomed to abrupt mood swings, night by night, between romance, heroism, horror, and lunatic farce. He develops a taste for this constant change of pace, and the more radical the changes the better. On any given night in my two seasons in Lakewood, I could be a crotchety uncle, a cowardly French soldier, a sadistic courtier, an Egyptian eunuch, a cockney thief, a foolish aristocrat arrested in a brothel, and, yes, a crackpot conjuror. I went through ten pounds of greasepaint, wore out a dozen costumes, and had the time of my life.

T

hese two summer seasons put me into a heightened new relationship with my father. The air was thick with Oedipal complexity. I was his employee now, one of a gang of working actors who were not always happy campers. Most were veterans of several seasons with my father. They liked and respected him, but they were far from reverential. Of the twelve plays that I appeared in, Dad directed half. For the first time, I watched him at work, up close and personal. I witnessed his interactions within his own company, I compared him with other directors, and I took his measure. The festival’s workaday routine and the actors’ occasional grumbling took their toll on my filial idolatry. My high estimation of him never flagged, but, in my eyes, his untarnished image gradually gave way to a much more realistic picture. I began to see his undeniable strengths counterbalanced by weaknesses that I’d never quite noticed.

In general, my father’s directorial modus operandi was to find the best actors he could get, put them together with a slate of Shakespeare’s plays, and just let ’er rip. Such an approach was daring but dodgy. By any rational standard, he scheduled too many productions in too little time, requiring plays as complex and demanding as

Hamlet

to be mounted in as few as eight days. Besides, the quality of acting in the ensemble was wildly inconsistent. As a consequence, it was almost impossible to achieve a consistent company style. By necessity, Dad’s direction tended toward the “louder/faster” school. A lot of attention was given to the breakneck pace of the dialogue and the running time of the entire play. He was even known to bring a kitchen timer to rehearsals and require that scenes finish before the timer went off. When he was directing, our workdays were supercharged with his genial, positive energy, but there was little time given to subtlety or detail. He was impatient with close textual analysis, nuances of character, emotional truth, or historical context. Indeed, his most frequent direction to his actors was to face the audience, fill up your lungs, and

“just speak the words!”

For him, Shakespeare carried a kind of biblical weight, an almost magical power. He fervently believed that if you just speak the words, everything else will fall into place.

If Dad’s “faith-based” approach was sometimes haphazard and off-key, it often paid miraculous dividends. His passion for Shakespeare’s work was infectious, and the youthful energy and raw talent of his actors often carried the day. And every once in a while, watching him at work like a bench player eyeing his coach from the sidelines, I would witness flashes of genuine brilliance.

In

Romeo and Juliet

I was cast in the trifling role of the Second Musician, so I had plenty of time to watch. A day before our first performance, the cast was plowing through a daytime dress rehearsal. Things were not going well, but my father, sitting in the dark at the back of the house, was letting the actors struggle through the play without stopping. I sat in the first row, watching the sodden production lurch from scene to scene. Chiefly responsible for the theatrical doldrums up onstage was the actor playing Romeo. He had a flowery name, six syllables long, but I’ll call him Devereaux. Devereaux was a vain, baby-faced pretty boy, consumed with narcissistic self-regard. His favorite pastime was sitting languorously at his makeup table for an hour before every show, staring at himself in the mirror, his face framed by a whole gallery of photographs of Elizabeth Taylor in

Cleopatra

. As Romeo, Devereaux’s coiffed blond hair, meticulous mascara, and fey, self-styled costume were far more important to him than his character’s impetuous flesh-and-blood passions. Romeo’s scalding love for Juliet was barely an afterthought.

As I sat and watched the dress rehearsal that day, Romeo and Juliet began their famous balcony scene. Five minutes into it, Dad broke his resolve to let the cast slog through to the end. He unfolded himself, stood up, and walked all the way down the aisle, bringing the two actors to a halt. He put aside his notes and began to speak, his demeanor exuding an eerie forced calm. With an almost canine sensitivity, I recognized that tone in his voice. I shifted in my seat, sensing a gathering storm. He directed all of his words toward Devereaux. They were carefully chosen and enunciated, as if he were composing an academic essay.

“The problem with the production as it now stands,” he began, “is that it has no Romeo.”

That quiet declaration hit Devereaux like a rifle shot. He lowered himself to the floor, carefully arranging his powder-blue cape with its dainty pink piping. His eyes were glassy and his body slumped as my father’s gentle critique slowly built in intensity. Peppering his speech with quotes from the text, he described Romeo’s renegade sexuality, his hotheaded irrationality, his feverish fixation on Juliet. With every sentence he grew louder, more passionate, almost angry. Within minutes, his helpful prodding had bloomed into a full-blown tirade.

“If

this

Romeo tried to vault Juliet’s fence,” he bellowed, “he’d break his stick! If he climbed in bed with her, he wouldn’t know what to

do

! That’s not Romeo! Love for Romeo is not flowers and perfume. It’s urgent, it’s sweaty. He’s an animal! He’s carnivorous! So is Juliet! If he doesn’t have fire in his loins, then neither does she! You’re giving the other actors onstage nothing! Romeo is not there! And without Romeo, the whole play is as limp as a limp

dick

!”