Drama (24 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

In my Act II scene, stage manager Annie Keefe had to calculate exactly how much time it would require for me to take an actual bath. Hence, when the moment came, I staggered offstage in my uniform, hastily cast it off, jumped down into the empty tub and began a bizarre bath-pantomime. Except for the absence of water, it was accurate in every detail. I crouched stark naked in the tub, pretending to scrub myself clean. I dipped my head under invisible water, ran my fingers through my dry hair, and frenetically rubbed imaginary mud and sweat off every inch of my body. Three or four fully clothed crew members stood above me in the semidarkness, watching indifferently. One of them was Annie Keefe, holding a stopwatch and timing me. I was a naked man in an empty plywood box in an empty theater on an October afternoon in New Haven, Connecticut. I was the main character in a strange, surrealistic dream. For a fleeting moment, my brain departed my body. It floated above me and looked down at this naked, ludicrously contorted young man. A conscious thought formed itself, one that has passed through my mind a hundred times since:

What am I doing with my life?

I was acting, of course.

A

nd not just acting. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was also preparing for my first major breakthrough in show business. And by glorious good fortune, that breakthrough was linked to a stunning work of dramatic art.

The Changing Room

fulfilled the promise of theater like nothing that I’d ever been in. It had an overwhelming impact on our audiences. On several occasions, spectators needed to be literally helped out of their seats. As emotional exercise, it was visceral and cathartic. The show was an instant success at Long Wharf and the subject of glowing national press. Lavish praise was heaped on the play, the production, and the entire company. I was one of the few actors singled out. For the first time I was mentioned in the pages of

Time

magazine, where I chose to ignore the fact that I was referred to as “George Lithgow.”

We began our run at Long Wharf with the sense that, for nearly all of us, this was the finest piece of theater we had ever been a part of. But the best was still to come. After one of our last performances, we were summoned into the empty theater. An elegant, expansive man named Charles Bowden introduced himself to us. He grandly announced that he had assembled a team of producers to transfer the show, exactly as we were performing it, to the Morosco Theatre on Forty-fifth Street in New York for the following March.

We were going to Broadway!

The notion of acting on Broadway had been almost as foreign to me as acting in movies. Years before, I’d filled out my application for a Fulbright grant. One of the questions on the form asked how I would apply my experience if I were to study abroad. I had written three words: “American repertory theater.” This was the world I’d come from and where I intended to return. At the time it represented the extent of my ambitions. My one vainglorious flirtation with the movies had done little to broaden those ambitions. My career at Long Wharf was only a couple of months old, but I’d felt no need to seek a better setting elsewhere. It felt like home. And now one of my very first Long Wharf productions was propelling me to another level of the business, one that I had thought I would never attain. I was astonished and I was elated, in equal measure.

The next few months passed quickly. The timing of our projected Broadway opening allowed me to perform in two more Long Wharf shows. Several actors from

The Changing Room

acted in those shows as well, so for all of us the air was charged with electric anticipation. Jean and I retooled for another big move. Most of the company showed up at our Branford apartment for a pre-matinee brunch celebrating Ian’s first birthday. In February the

Changing Room

cast regrouped in a New Haven rehearsal studio. It was Valentine’s Day and, by chance, Michael Rudman’s birthday. Charles Bowden and his producing team were on hand with an enormous birthday cake. Bowden had secretly slipped the actors sheet music for “My Funny Valentine” and we surprised Michael with a hearty rendition of the song. Spirits were soaring as we set about putting the show back together for New York.

Jean, Ian, and I took up temporary residence in the Upper West Side apartment of a touring actress friend. Under Michael Rudman’s stewardship, the company installed the show in the venerable Morosco Theatre, where it looked better than ever. The Morosco has long since disappeared, making way for an enormous Marriott Hotel on Times Square, but back then it was a prime legit house in the heart of the midtown theater district. The old building resonated with American theater lore, having been the site of the first runs of such classics as

Our Town

,

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

, and

Death of a Salesman

. That season our show was within shouting distance of

Pippin

,

That Championship Season

, and

A Little Night Music

. Heady with excitement, we moved into our dressing rooms, linked up with working pals in adjoining theaters, and staked out our favorite restaurants and bars. We previewed. We opened. That night we gathered at Sardi’s after the show to celebrate. The

New York Times

review was read out loud. We were a smash.

Opening night was March 7, 1973. Less than three weeks later, on March 25, in what was surely the shortest period of time between a Broadway debut and a Tony victory, I won that year’s Tony Award for Outstanding Featured Actor in a play.

S

ure. Acting awards are trumped-up, corrupting, meaningless, and unjust. They are anti-art. In a profession that relies on a collaborative spirit, they pit artists against one another. They are the wellspring of more envy, anger, resentment, and covetousness than anything else in show business. Awards turn us into appalling hypocrites. We airily dismiss their importance but we secretly long for them. When we win them, we are often at our very worst. Our acceptance speeches are generally a graceless cavalcade of pomposity, crocodile tears, and egregious false modesty. An award winner is usually the only person in the room who is genuinely pleased by his prize. By varying degrees, everyone else is bitter, begrudging, and judgmental. Often this even includes the cast of a winner’s very own show. All things considered, it is far better to never win an award for acting.

That said . . .

Winning a Tony Award was the happiest moment I’d ever experienced in a theater. Nanette Fabray opened an envelope and read my name. Applause exploded all around me. I lurched up the steps to the Imperial Theatre’s stage in my rented tuxedo, my ruffled shirt, and my black velvet bowtie. I stared out at the brightly lit mass of beaming faces, my heart racing like a hummingbird’s wings. By some miracle I managed to recite every word of my carefully wrought speech. Seeing a grainy tape of that moment a couple of years ago, I saw none of the elation I remember feeling. I looked like a tremulous, stammering schoolboy. And with the lingering traces of my unwitting British accent, I sounded like a pretentious fop.

Oh, but it was wonderful. All actors strive for that elusive moment when the quality of their work is matched by the measure of its success. Such an occurrence is all too rare. Many of us go through our entire careers without it happening once. And here it was, on my very first outing. Between a Broadway debut and a Tony Award, I barely slept for the entire month of March.

The twin events ushered in a springtime full of sparkly new pleasures. The city, so recently an impregnable fortress of rejection and failure, suddenly flung open its doors. I and my

Changing Room

cast mates became fixtures at Downey’s, Lüchow’s, Jimmy Ray’s, and Joe Allen. The play won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award and we hobnobbed with the likes of Clive Barnes, John Simon, and Walter Kerr. We formed an unbeatable softball team for the Broadway Show League in Central Park. Our press agent cooked up a publicity stunt pitting us against a squad from the star-studded all-female cast of

The Women

(Alexis Smith! Rhonda Fleming!

Myrna Loy!

). I was sprung loose from our show for three days for my network TV debut, appearing in a tiny role with the great Jason Robards in a Hallmark Hall of Fame production of

The Country Girl

. Blessings rained down on me.

One day halfway through our time at the Morosco, an envelope arrived for me at the stage door. It contained a kindly note from John Stix, from Baltimore Center Stage. Without a trace of sour grapes he congratulated me on

The Changing Room

. In particular, he complimented me for having made such a wise decision in choosing to accept an offer from the Long Wharf Theatre.

O

nce I settled into the run of the show, Jean and I sought out another temporary housing situation. Back in New Jersey, my parents were now living outside of Princeton, renting a farmhouse surrounded by soybean fields near the village of Plainsboro. There was plenty of room for my family of three, so we moved in. I commuted daily to New York for my shows. Every night I sat on the train and read the next morning’s edition of the

New York

Times.

It was filled with coverage of the Watergate hearings and of the epic downfall of Richard Nixon. The extended Lithgow family, like the rest of liberal America, basked in the warm glow of political schadenfreude

.

My parents loved our company. In the sunny New Jersey countryside, Ian was in toddler heaven. My father and I replayed every game of the historic chess face-off in Iceland between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky. On a day off from the show, the cast of

The Changing Room

traveled down en masse for a picnic in the expansive yard of the Plainsboro house. For Jean and me, it was the happiest time in our marriage.

But there was something seriously wrong with this picture. My mother, my father, and my little sister, Sarah Jane, had moved out of Princeton, having lost their university-owned apartment. My father was no longer employed by Princeton University. He was out of a job. During a sabbatical from his duties as artistic director of McCarter Theatre, the Princeton administration had seized the moment to unceremoniously fire him. While my parents’ pride might have spurred them to move far away from the source of such an indignity, they had a compelling reason to stay in the area. Having lived in Princeton for eleven years, Sarah Jane was the only one of their children to spend all of her childhood in the same school system, the only one who had never suffered the trauma of being the new kid in town. Mom and Dad wanted to spare her that. They wanted her to finish up at Princeton High School before they left. So they had rented the Plainsboro farmhouse, doing their best to put on a brave face, enjoy a far less stressful life, and avoid all thoughts, as they surveyed the vast fields surrounding them, of being put out to pasture.

When my father was let go from Princeton, the rationale handed down from above was that the quality of the company’s work had slipped. Arthur Lithgow, they declared, was no longer achieving a sufficiently “exciting” level of theatrical fare. This explanation enraged me, especially as it was couched in the fatuous phrases of Ivy League doublespeak. What did a bunch of stuffy, hidebound academics know about professional theater? Who did they think they were? And what the hell did they mean by “exciting”?! But beneath my indignation there was a hidden strain of guilt. My father had lost his job for many of the very reasons that I had chosen to stop working for him. Like his Princeton employers, I had wanted something better. I had left his company at the very moment when he most needed my support. And now my career had taken off like a rocket just as his had suffered a devastating setback. He was fifty-seven years old, eight years younger than I am as I write these words, and he had no idea where he was going next.

For both my father and me, it was a season of deep conflict and painful contradiction. Success was countered by failure, pride by guilt, soaring confidence by gnawing doubt. I suppose that my dad’s circumspect nature stood him in good stead during that time. It was certainly a boon to me. I can only imagine his hidden feelings of injury and humiliation caused by his treatment at the hands of Princeton University. He must certainly have succumbed to occasional spasms of envy directed at Arvin Brown, and personal hurt that I had chosen Arvin’s theater over his. But outwardly he remained his sweet and genial self. To my eyes his delight in the success of

The Changing Room

was warm and genuine. He welcomed the cast to his home with effusive good will. If the events of the preceding year had taken their toll on him, he never showed it. He never betrayed a hint of self-pity nor made the slightest bid for sympathy. He may have revealed his bitterness and disappointment to my mother, but none of us saw a glimpse of it. Only in retrospect have I come to see what a Herculean effort that must have been for him. By keeping his pain to himself, he allowed me my first undiluted taste of success in a profession that had treated him shabbily and without mercy. It was a father’s selfless gift to a son. I love him for it.

Mr. Pleasant

I

t is not for nothing that an actor is said to “give a performance.” At its essence, acting is a gift to an audience, whether that gift is delivered from a stage or a screen. An actor gives something to an audience and, with any luck, the audience gives him something in return. When this curious transaction is successful, everybody is happy. The audience is elated and the actor is fulfilled. Things get a little warped when the actor loses sight of his mission, when he forgets its essential generosity, when he feels that he is not getting his due, that his audience is not sufficiently responsive, grateful, adulatory. At such moments, another diva is born and unleashed on the world. All actors are susceptible to this syndrome. Every single one of us. Applause is a narcotic, and we’re all prone to addiction. The great challenge is to always remember a simple truth: that acting is not about

us

, it’s about

them.

I once worked with an actor who had forgotten that truth long before, if indeed he had ever known it at all.

I’m disinclined to defame this man, so I’ll call him Rock. Rock Masters. I acted with him in a movie. I’ll return to him in a moment.

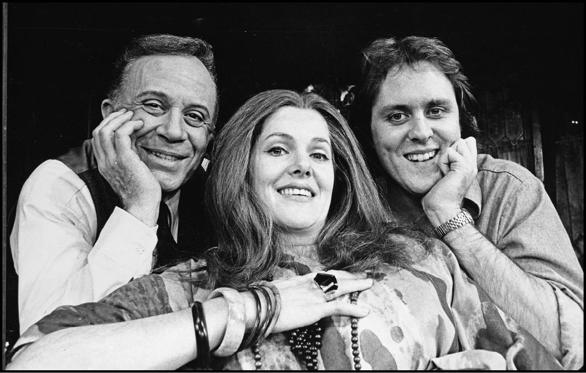

Photograph by Martha Swope. Courtesy Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

After the heady success of

The Changing Room

, I spent an entire year on Broadway performing in a dopey play called

My Fat Friend

. This was a campy four-character British farce whose main plot line concerned the drastic weight loss of its portly young leading lady. The play was a forgettable trifle, considerably elevated by the blithe performances of two terrific actors, Lynn Redgrave and George Rose. In the role of their dour, young Scottish flatmate, I had a great time playing second banana to these two expert comedians. I admired them both deeply and loved their bubbly comradeship. Besides, a year’s salary on Broadway was an unaccustomed luxury. It allowed Jean, Ian, and me to set up New York housekeeping again, in a bigger apartment with a comfortable, predictable daily life. But due to an insecurity born of my earlier hard times in the city, I clung to the show for far too long. After an entire year on Broadway, I joined Lynn and George on tour to Detroit and Toronto. When that was over, I still couldn’t let go. I soldiered on without them in a slapdash New Jersey stock production of the play at the Paramus Playhouse on the Mall. A year of weekly paychecks had created a severe dependency in me, and I desperately needed to break it. A change was long overdue.

Happily, a filmmaker friend of mine came calling. Him I will call Paolo. Paolo had dreamed up a deliciously lurid suspense film set in Europe. I’ll call it

Interdit

. Shooting was all set to start and he wanted me to be in it.

Interdit

was second-generation Alfred Hitchcock. The leading role in the film is a man who falls in love with a much younger woman. This infatuation pulls him out of a long period of his life during which he has grimly buried himself in his work. The man has a longtime best friend who appears to have grave doubts about the disturbing intensity of his old friend’s love for the young girl. But true to the film’s Hitchcockian antecedents, the friend’s kind-hearted concern is not all that it appears to be. I played the devious best friend. The starring role was played by Rock Masters. Working with him would prove to be more than just a job. It was an education.

By this time in his career, Rock Masters was running on fumes. He was navigating the rough waters of a middle-aged leading man’s faltering career. His genial manner was tinged with desperation. For him, starring in

Interdit

was a chance to regain some lost credibility in the movie business. The plot of the film paired the two of us in a complex psychological chess game, full of mystery, duplicity, and shocking revelations. It was a meaty on-screen relationship, the kind most actors would kill for. I had practically salivated when I first read the script. I suspect that Rock was pretty excited, too. But he could have been forgiven for feeling a little concerned when he learned that he would be partnered with an unknown, untested New York theater actor half his age.

When the film’s cast and crew assembled on location in Europe, things started off promisingly enough. As so often happens in the odd world of filmmaking, I met Rock for the first time at a tedious afternoon-long session of makeup tests. That very morning I had stepped off a plane after a red-eye flight from New York, having delivered my last performance of

My Fat Friend

back in Paramus only twenty hours before. I was stupefied with jet lag but I managed to strike up the beginnings of a friendly working relationship with both Rock and his young costar, a Gallic beauty whom I’ll call Julianne Clement. The makeup tests were conducted under the watchful eyes of director Paolo and his cinematographer (call him “Laszlo”).

A lot was at stake. The plot of the film cuts back and forth between two time periods. Rock was fifty and I was just shy of thirty, but we had to look the same age in every scene. Hence half the time I needed to look twenty years older than my actual years and the other half Rock needed to look twenty years younger. This is what made the makeup tests so tricky and time-consuming. Through the fog of my jet lag I heard long, urgent discussions among Paolo, Laszlo, and Rock. Appearances, it seemed, were going to be a big issue on this film.

Not just a big issue. A big problem. Appearances were at the heart of a fading film acting tradition to which Rock Masters still fiercely adhered. According to this tradition, good looks were everything. Years before, Rock had carefully constructed a distinctive screen persona. He wasn’t about to diverge from it. Thus he had devised several strategies to ward off incremental signs of change. His hair had begun to turn gray and thin out. He dyed it jet-black and battled hair loss with implants. These were several-inch-long strands of hair. He wrapped them around his scalp like a turban, massaged them into a sculpted helmet, and instructed the film’s hairdresser to stipple the underlying patches of bare scalp with inky black stain. To Laszlo’s dismay, Rock had schooled himself in the art of movie lighting. Whenever the crew had finished lighting a scene, Rock would stride onto the set with a tiny mirror, hold it eight inches from his eyes, and instruct the gaffer to add a tiny spotlight, called an “inky,” to lend an extra sparkle to his eyes. He was also inordinately concerned with appearing too short on film. Hence he wore inch-high lifts inside his shoes, insisted on standing on an apple box in every two-shot, and lagged back a step or two whenever he walked down a flight of steps with another actor.

And then there was that contentious issue of makeup. For years Rock had used the exact same bronzer to give him the manly face of a rugged, leathery cowboy. On every film he brought along his own supply. This had been the subject of the muttered conversations on the day of those makeup tests: Paolo wanted Rock to dispense with his beloved bronzer. The character had led a sequestered, office-bound life for twenty years, Paolo argued. It didn’t make sense for him to look like The Marlboro Man. In test after test, Paolo coaxed Rock to use less and less makeup. Finally Rock relented and Paolo was satisfied. But a week later, on the first day of shooting, Rock showed up on the set having already done his own makeup back at his hotel. He’d used the same old bronzer, slathered on thicker than ever. He was as ruddy as Sitting Bull, as if all those makeup tests had never happened. Paolo fumed. Laszlo despaired. Rock won.

This was only our first day of shooting. There was much more to come. Day by day I began to perceive Rock’s priorities. It seemed that film acting to him was not about building a character, shaping scenes, or relating to other actors, and it certainly wasn’t about “giving to the audience.” It appeared to be about the everlasting pursuit of his own close-ups. To this end he had invented a system of doling out his energies. In the coverage of any given scene, his acting would be wooden and monotone all through the masters and two-shots. Only when he was being filmed in close-up did his performance come alive. By this means Rock calculated that the director and editor would be forced to heavily favor his close-ups when it came time to cut the scene together. And it wasn’t enough for him to supercharge his own close shots. When it was time for his fellow actors’ close-ups, he would lifelessly mumble his lines off camera, giving them almost nothing to play off.

Sometimes Rock would go even farther. In one scene halfway through the script, he and Julianne were locked in a passionate embrace. It was first shot from an angle that favored Rock. His face was nicely framed as he embraced and kissed her. Next the camera and lights were reset for an angle that favored Julianne. As Rock embraced her with his back to the camera, he lifted his shoulder, covering half her face. Paolo cut the take and mentioned to Rock the little problem with the shoulder. Rock assured him that he would make an adjustment on the next take. The camera rolled again. Once again his shoulder rose up, and once again Julianne was blocked, tilting her face backwards as she struggled to be seen. Paolo repeated the same note. Rock cheerfully acknowledged it. Take three. Up went the shoulder. Another note, another nod, another take, and once again the shoulder went up. The three of them danced this little minuet five or six more times. The tension on the set approached the boiling point. Everyone felt it but Rock, who remained relaxed, affable, and eager to help out. At last Paolo gave up and moved on to the next setup. Another round had gone to Rock.

A year later when the film was released, there was that embrace up on the screen. It plays in only one angle, with Rock’s ardent face nicely on display and Julianne seen from behind. You can see the editor’s dilemma. Why feature a shot in which a beautiful young starlet looks like a drowning woman, struggling to come up for air?

As the shooting went on, I watched all of Rock’s moves with a kind of queasy wonderment. I was a starry-eyed innocent with the scales falling from my eyes. Confronted with all of these elaborate mind-games I began to self-protectively develop a few of my own. I made myself into Rock’s guileless disciple, peppering him with questions about his technique as if I had never set foot on a film set. I figured the more I was attentive to him, the less he would ambush me. For his part, Rock relished the role of crusty mentor. He would take me into his confidence and share with me his crafty wiles.

One day on a city street, Rock and I were shooting a scene where we simply walked out of a building and climbed into a car. Paolo was covering the two of us in a broad master shot, followed by a closer shot of Rock as he got behind the wheel. Rock wanted to be sure that the closer shot would end up in the final edit.

“Watch this,” he told me.

As we shot the master, he would do something slightly wrong on every take. He would trip on the curb, drop his briefcase, bump the fender of the car, or fail on his first attempt to open the car door.

“You see?” he said.

“See what?”

“Now they’ll have to use the closer shot.”

“That’s incredible, Rock!” I said. “What do you call this?”

Rock grinned and winked at me.

“Trickery,” he growled.

Despite all of this on-set gamesmanship, Rock’s demeanor was amiable, courteous, and masterfully disingenuous. Anyone visiting the set of

Interdit

would have envied us the privilege of working with such a gracious, considerate star. But movie crews are a cynical bunch. They’ve seen it all and they catch on fast. In no time they became aware of every hoary trick Rock was playing. He was fooling no one, least of all Paolo and his editor. By the end of the shoot, everyone on the set was referring to him behind his back by the pet name they had coined for him. They called him “Mr. Pleasant.”

Interdit

was released in the U.S. under another name. Its French title had not survived the rigorous market testing of its American distributor. It had a middling success in the States but did little to revive Rock Masters’ career. It was the last substantial leading role he ever played in films. But I took no pleasure in his decline. I’d actually liked the man. In fact, I was pleased for him when he recently scored a modest triumph in his late seventies, playing a small role in a Hollywood sci-fi blockbuster. In retrospect, his strenuous self-aggrandizement during the filming of

Interdit

strikes me as sad, self-deluding, and almost poignant. He was clinging to a Hollywood that no longer existed. He was playing by rules that no longer applied. Teaching me those rules was his version of an actor’s generosity. Working with him had been an education all right. But it was an in-depth tutorial in how not to act in a movie.