Drama (6 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

The Good Boy

A

fter Oak Bluffs and Waterville, the world of The Stockbridge School was distinctly exotic. This was not your typical New England prep school, full of children of great wealth and patrician breeding. Oh no. With its renegade faculty and its raffish student body, The Stockbridge School was just the opposite. Its kids were roughly divided into two groups. Half were lefty New Yorkers, many of them Jewish and many of them children of divorce. The other half was a polyglot mix of foreign students, in keeping with Hans Maeder’s internationalist mission (the United Nations flag flew alongside Old Glory at the school’s entrance). An ultra-liberal, ultra-casual atmosphere prevailed. Dress codes were nonexistent. Every teacher was called by his or her first name. Folk ballads and union songs filled the air. The eighty-plus students were made to feel a part of a huge, mutually supportive family, in many cases replacing the fractured families they had left behind. The school shut down many years ago, unable to survive after the messianic Hans departed the scene. But while it lasted, it was an artsy, outdoorsy, gloriously anarchic mess of a place. In all of its years of existence, its most notable alumnus by far was Arlo Guthrie.

Although nestled in the Berkshire Hills in a splendid New England setting, the school was far from lavish. Serviceable cinderblock classroom buildings and dorms surrounded the large, white-shingled “Main House.” The Lithgow family was housed in a tiny converted icehouse, painted gray with blue trim. This time, there were only four of us—my mother, father, three-year-old Sarah Jane, and me. David was at college now and Robin was enrolled, tuition-free, in the school’s tenth grade, a boarding-school student a hundred yards from home. Hans wanted me to enroll, too. The school started in ninth grade, so he insisted that I skip a year and join the incoming ninth-graders. I demurred. I was worried about being a year younger than the rest of my class, and my parents shared my misgivings. Besides, I wanted to reconnect with my old gang at the public school in town, a half hour away by school bus. Hans was a hard man to refuse, but I managed somehow.

Though merely a faculty brat, I immersed myself in the quotidian life of the campus. The family ate most of our meals in the community dining hall in the Main House; I knew every student by name and befriended several of them; on Saturdays I tagged along on the students’ “free days,” traveling by bus to Pittsfield for burgers and movies; I rooted for the school soccer team, at matches played amidst the dazzling autumn foliage; I painted scenery for my father’s wildly ambitious school production of

Peer Gynt

; and on Wednesday nights I attended an extracurricular crafts class run by a genius teacher named Bill Copperthwaite. From Bill I learned how to stitch leather bags, carve wooden bowls, and build furniture, skills which, though they lie dormant, I have retained ever since. All of this made me a de facto student of The Stockbridge School, even though most of its genuine students regarded me as little more than an eager, omnipresent mascot.

But all of this activity and bonhomie constituted only one-half of my schizophrenic Stockbridge existence. The other half was that of a Stockbridge townie. After the tearful transitions of the preceding year, starting eighth grade at my former school was a cakewalk. Everything was familiar. No real adjustment was necessary. And, as spotty as my education had been until then, I was a perfectly good student. Three years before, as a cowering fifth-grader, I had been terrified of the burly, glowering, red-faced eighth-grade teacher, Mr. Blair. But having become his student, I now found him colorful, crusty, and endearing. Despite his gruff demeanor, I won him over in no time and swiftly assumed the status of teacher’s pet.

That first day, when I strode into class, my old friends were surprised and delighted, welcoming me back into the fold like the Prodigal Son. They were great guys—Vincent Flynn, Billy Sheridan, Peter Van Lund—and we picked up exactly where we had left off. In a replay of my fifth-grade year, the quaint town and its surroundings provided the setting for all kinds of adventures. In the autumn we climbed to the top of Laurel Mountain and explored the caves of the mysterious “Icy Glen”; when winter descended, we hiked in deep snow and skated on remote lakes and ponds; and in the spring, on the first day of fishing season, we rose before dawn and staked out a perfect spot on the banks of the Stockbridge Bowl, an impossibly picturesque lake in the heart of the Berkshires. The girls were pretty great, too. And although in matters of the heart I was still hopelessly shy, my fantasy life was vivid and feverish. A sweet girl named Carol Lowe, the object of an ardent fifth-grade infatuation, was still there, as dewy as ever.

A

problem was emerging, but I didn’t recognize it at the time. I had been forced to quickly adapt, three or four times, over the course of some crucially formative years. And here in Stockbridge I was leading a spirited social life with two separate and completely different crowds. I was developing Zelig-like skills to manage this odd dual identity. At first blush, this seems like an entirely good thing. After all, I had progressed far beyond the puling insecurity of my Waterville days. I was active, genial, and well liked in both of my social spheres. But in retrospect I have come to see a troubling side to this rapid-response adaptability. In my struggle to fit in, appearances had become everything. I was consumed by an eagerness to please, to cause no offense, to make no waves, to stir up no trouble for my stressed-out parents (however deftly they had hidden their stress from me). I was becoming a good boy, an utterly, unimpeachably

good boy

, and not necessarily in a good way. For when appearances are everything, the trade-offs can be poisonous. A good boy can be capable of appalling secret cruelties.

There was a girl in the freshman class at The Stockbridge School whom I shall call Esther Furman. Nobody liked her. From her first day at the school, she had been a social pariah. At supper one evening, as I sat with a group of older boys in the Main House dining room, one of them offhandedly mentioned someone named “Fau.”

“Fau?” I said. “Who’s Fau?”

“Esther Furman,” he answered drily. “It stands for ‘fat and ugly.’ ”

The boys cackled with laughter, and to my shame I laughed along with them. “Fau,” it turned out, had become Esther’s commonly used nickname around the school. In the next few weeks, I heard it dropped so often that I felt sure that Esther herself must have heard it too. And, most painfully, she must have heard what it stood for.

Starved for companionship, Esther turned to me. She had been ostracized by her fellow students, but since I was not one of her fellow students, she sought me out. In the dining hall, I would typically sit with the freshman boys, eager to be included. Esther would plop down next to me and chatter away happily. True to my carefully cultivated good-boy nature, I was pleasant and receptive (and, in fact, there was nothing about Esther to particularly dislike). But I was cringing inside. I feared that this hungry, hapless girl was ruining my bid for acceptance among the sophisticated young cynics of The Stockbridge School.

Everywhere I turned, there was Esther. She even took to waiting for me on spring afternoons, at the spot on the country road where the school bus discharged me. She began to fix on the idea of going fishing with me at the Stockbridge Bowl, off the school’s private dock. I was mortified at the thought of being seen with her by any of my older friends, at being lumped with Esther as the object of their ridicule. To put her off, I made up all manner of bogus excuses. Weeks passed but Esther was cheerily persistent. At one point I claimed that I couldn’t fish because my reel was jammed and I didn’t have the proper tools to fix it. She said she would help. She would find some needle-nose pliers and meet me at my house at four. If we managed to repair the reel with the pliers, we could go fishing at last.

At the appointed hour, I was alone in the little icehouse, crouched in my bedroom. I heard Esther’s footsteps along the wooden boards of the porch. She knocked at the door. I said nothing and sat perfectly still, hoping she would think I wasn’t home. She knocked again.

“John?”

I stayed mum.

“Are you there?”

Still mum.

“I have the pliers.”

A long pause. My heart was pounding.

“I know you’re in there. I have the pliers. John?”

And I finally answered, with the three most hateful words I’d ever spoken.

“Forget it, Fau!”

After a moment, I heard footsteps again as Esther walked away. I never spoke to her again. I could barely even look in her direction. Everyone I knew continued to think of me as John, the good boy. But not Esther. Not anymore. And not I.

Someday I would be an actor. One of the most basic things an actor must learn is that human beings are capable of anything. Each and every one of us can be noble, courageous, and kind. But we can also be cowardly, cruel, and contemptible. And all of these qualities, good and bad, can often erupt from nowhere, when you least expect them, in the least likely people. Good people can do terrible things, bad people can astonish us with their goodness. This is one reason why life constantly surprises us. It is also, incidentally, at the heart of the best comedy and the best drama. We are capable of anything. A caustic three-word phrase barked out in an empty icehouse on the campus of The Stockbridge School was my first and most startling demonstration of that truth.

Enter Messenger

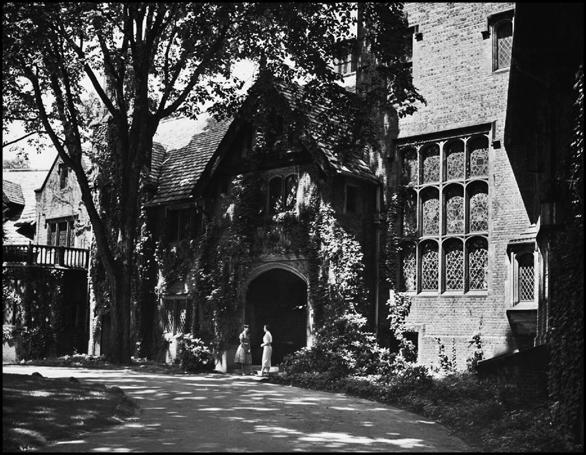

Courtesy Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens.

F

or two years of my life, I lived on a fifteenth-century English estate. My backyard stretched out across a hundred acres. A vast greensward led up to a stately manor house graced with gables, parapets, Tudor beams, and hundreds of leaded-glass windows. The house had sixty rooms, including a great hall, a music room, a library, a billiard room, and a solarium. On the walls hung Old Master paintings, tapestries, armor, weaponry, and the stuffed heads of a dozen wild animals. A sycamore allée extended from the house in one direction, with seven-foot rhododendron bushes growing at the foot of the massive trees. In the other direction, a delicate birch allée led to twin gazebos overlooking meandering lagoons. There was a sunken English garden, a Japanese garden, a tennis court, and a croquet lawn. Fountains splashed in the middle of a reflecting pool below a broad back terrace. An old Scottish couple named Sandy and Annie were the deferential retainers of the household. Rangy, red-cheeked Wilbur Turberville was the affable chief groundskeeper, tending to the lawns and flower beds. Flowers were everywhere.

Despite its grandeur, the estate had fallen prey to neglect and disrepair. Less than half of its formal gardens were maintained. Scrubby trees had long since sprouted through the crumbling asphalt of the tennis court. Overgrown reeds suffocated the abandoned lagoons where two feral swans fiercely guarded their swampy domain. A couple of bedraggled peacocks occasionally strutted out into the open and pierced the air with mournful screeches. Sandy, Annie, and Wilbur were themselves ghostly holdovers from a lost era, their prosperous employers long departed.

Besides the gabled manor house, there was a gatehouse, a gardener’s cottage, and a carriage house. On the second floor of the carriage house, just above the empty stables and the porte cochère, lived the Lithgow family.

Where the hell were we now?

We were in Akron, Ohio. It was 1959. I was fourteen years old.

The estate was Stan Hywet Hall, the dream house of the early-twentieth-century rubber magnate F. A. Seiberling. Seiberling died in the mid-1950s, having long since lost the bulk of his fortune. As a tax dodge to benefit his offspring, he bequeathed his decaying Xanadu to the city of Akron, providing the town with a splendid site for a new civic cultural center. Noting his history of cultural midwifery, the board of directors of the fledgling center contacted my father. They invited him back to Ohio to become the center’s first executive director. With dreams of a new incarnation of his beloved Shakespeare festival, performed on the back terrace of a Tudor manor house, he jumped at the offer. After a single year on the faculty of The Stockbridge School, he was on the move again. Like a tennis ball thwacked back over the net, the family once again trekked out to Ohio, the old Studebaker groaning under the weight of our worldly possessions.

One evening, back at The Stockbridge School, my parents had sat me down in the living room of the icehouse and revealed to me their latest plans. This time I remember my response. I burst into tears, stormed out of the house, and ran off into the night. Alone in the middle of a field, surrounded by the Berkshire Hills and lit up by moonlight, I cried out at the top of my lungs, “WHY ME?! WHY AKRON?!” Looking back, I have to admit that this was all a bit theatrical. There was nobody watching, but I was acting my head off. Perhaps this was only fitting. In my next two years in Akron, events would begin to propel me, without my even knowing it, toward a career in the theater.

O

ver the course of those two years, I was a ninth-grader at Simon Perkins Junior High School and a tenth-grader at John R. Buchtel High (without ever learning who those two estimable Akronites actually were). These were my first big-city schools. With the onset of classes, I was confronted by throngs of students, multiple classrooms, thousands of lockers lining the halls, crowded assemblies, and clamorous pep rallies. I’d never seen anything like it. But this time the newness of the experience proved more exciting than overwhelming. And this time my skin was a little tougher. In an atmosphere of such energy and happy chaos, being a new student was far less of a trial than it had been in our preceding moves. Besides, I was welcomed into my new community in a surprising way. In those days, the curriculum of the Akron public schools was amazingly sophisticated. It accommodated and encouraged my most abiding, passionate interest. For two years, I was given the extraordinary luxury of starting every single school day with two elective periods of art.

And such wonderful classes! Every morning I would eagerly anticipate those early hours of school. Without fail, art class would launch me into the rest of my day with a heady creative rush. I did drawings in charcoal and ink, paintings with watercolors and acrylics, woodcuts, linoleum prints, silk screens, ceramics and mosaics. In those two years, my two teachers were twinkly older women, determined to unleash the creative juices of every one of their students. The second of them was named Fran Robinson. “Miss Robinson” was one of the best teachers I ever had. A distinguished craftswoman in her own right, she had invented her own highly individual medium. Using her Singer sewing machine, she embroidered fanciful tapestries in brightly colored thread. Occasionally her work would appear in the pages of

Art News

, and we would all feel the frisson of our teacher’s fame. Pricked on by her encouragement and inspired by her ingenuity and flair, I grew more determined than ever to pursue the visual arts.

After only one year, my older sister Robin had left The Stockbridge School and had joined the family on our return trip to Ohio. So once again she and I were two grades apart in the same school system. I loved having her back in the household. She had absorbed the urbane tastes and left-wing politics of her Stockbridge schoolmates, and she now set out to find like-minded friends in her new Akron crowd. She found them all right. There were about five of them, all smart, vital young women. But the tone of Buchtel High School was fiercely conservative (its affluent students were known around town as “The Cake Eaters”), so Robin’s new set of girlfriends was a tiny, heretical cabal. They reveled in their rebel status. They went to subtitled European films at Akron’s lone art house; they attended concerts of Glenn Gould and Andrés Segovia at the cavernous Akron Armory; they collected the records of Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and Theodore Bikel; they met early on Friday mornings before school to listen to entire Italian operas, following along in the scores. They even consorted with gaunt, long-haired college boys who drove them to nighttime meetings of the Young People’s Socialist League.

I watched all of this hard-core beatnik activity with a mixture of curiosity, timidity, and longing. In the school classrooms, athletic fields, cafeteria, and gym, I had quickly formed my own circle of Akron mates, stolid crew-cut white boys with whom I shared the reliable common language of pro sports and dirty jokes. But my attentions were divided. Just as I had in Stockbridge, I found myself conducting a two-tiered social life. I liked my gang just fine, but I was crazy about my sister and her older, hipper friends. Outside of school, I cultivated their bohemian tastes, tagged along on their esoteric outings, and clung to them like a burr.

From day one in Akron, my artwork was my highest priority. My natural facility made me the top student artist in my class. My paintings, drawings, and prints hung in the school hallways and won “Gold Keys” in citywide scholastic art competitions. In the midst of such feverish artistic activity, I never imagined for a moment that I would end up an actor. But in a couple of instances, the catnip of theatrical performance began to assert itself for the first time since those early years in Yellow Springs.

In the middle of ninth grade, I initiated a school project as far-fetched as it was ambitious. I set out to produce and stage a fifteen-minute piece of theater, unconnected to schoolwork and unsupervised by any teacher. The piece was the “gulling scene” from Shakespeare’s

Twelfth Night

. This is the scene in which the loathsome, puritanical Malvolio is tricked by four other gleefully vengeful characters in the play. I took the plum role of Malvolio and recruited schoolmates to play Sir Toby Belch, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, Fabian, and Maria. I gave everyone a little rudimentary direction and designed a simple set, consisting of a “boxtree,” which I fashioned out of painted masonite and lime-green crepe paper. After a few weeks of after-school rehearsal, we presented the results at a school assembly. The audience of ninth-graders were attentive, if slightly bewildered. There were no gales of laughter, and at the end they applauded with a kind of grave, respectful admiration. But the tepid reception didn’t bother me. For me, the show was fifteen minutes of undiluted triumph.

I remember almost none of the circumstances surrounding this bizarre event. Looking back, the whole thing completely astonishes me. How did it ever happen? When did I come up with such an idea? Shakespeare, performed by and for ninth-graders? Whatever possessed me? Was I crazy? Who did I think I was? Why, my father, of course. In hindsight, it seems quite clear that I was unconsciously aping him and his audacious schemes. Just like him, I was hurling Shakespeare at an unlikely, unpromising audience, and somehow making a success of it.

In tenth grade, the following year, I dusted off

Twelfth Night

once again. I reprised the entire gulling scene, this time playing all five parts. I performed it as a monologue in the category of “Humorous Declamation,” for Buchtel High’s National Forensic League team. On Saturdays, I would travel with a busload of brainy debaters to tournaments held in empty high schools all over north-central Ohio. The others would debate and I would perform, competing with teams from all over the region. I never did as well in my category as the debaters did in theirs.

Twelfth Night

, after all, was pretty heady stuff for a tenth-grader. In competition, I scored far fewer laughs than the students who recited the comic prose of Mark Twain and Robert Benchley, and I never won a thing. But watching my rivals in all those echoing auditoriums, I began to sense the beginnings of a smug certainty: I was the best actor in the house.

B

ut it was during my Akron summers that theater began to truly take hold of me. This was when my father produced the Akron Shakespeare Festival. This festival was only to last two summers, but in both of those summers, I immersed myself in the pungent world of yet another of Arthur Lithgow’s theatrical ventures.

For reasons that will shortly be revealed, the two seasons of the Akron Shakespeare Festival were presented in two completely different settings. The first was the terrace of Stan Hywet Hall, with the rear façade of the Tudor manor house providing a backdrop. For the festival’s inaugural season, my father chose a repertory of four plays that echoed the start of his triumphant Antioch run. These were the first four history plays from Shakespeare’s retelling of the War of the Roses—

Richard II

;

Henry IV

, parts 1 and 2; and

Henry V

. In keeping with his trademark style, the plays were staged simply, on a symmetrical arrangement of bare platforms, and performed by a small troupe of accomplished young actors imported from New York. But though the productions were straightforward and unadorned, the setting made them glorious. It is hard to imagine a more appropriate and more beautiful spot in America for this most English of historical pageants. The leaded-glass windows glinted behind Falstaff in his scenes inside the Boar’s Head Tavern; Richard II cried out in defeat, “Down, down I come!” from a crenellated parapet high above the audience; and when Henry V declaimed “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more!” the looming, starlit manor house stood in for Harfleur Castle.

Initially, I just hung around rehearsals, much as I had done years before during those happy summers in Yellow Springs. But by now I was a gangly fourteen-year-old. I had arrived at the age when, to the forgiving eyes of an audience, I could pass for an adult. By the time the company began rehearsing the two parts of

Henry IV

, the play’s big battle scenes forced the director, Edward Payson Call, to look for spear carriers anywhere he could find them. Inevitably, I was conscripted, and soon I was rehearsing five or six scenes in each of the last three plays. My first assignment was the only part I was remotely right for: I was one of Falstaff’s wretched platoon of army recruits, old men and young boys whom Falstaff dismisses as “food for powder.” I had a comic crossover with four other raggd peasants. For a weapon, I carried a rake.