Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (15 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

Mutual animosity is a necessary part of a band’s chemistry. It’s all egos in a band, anyway. Would you want to be in a group who were all clones of yourself? Pretty much anyone who wants to be a rock star is by definition a raging narcissist—then just add drugs! It may be one for all and all for one, but each one of us is an egomaniac, we’re all in it for gain and glory and showing the world how fucking great we are. It’s

me

! And when you have five me’s . . .

They say, “As long as you can keep that competition healthy, it’s all good, dog. . . .” But just try to be that reasonable when you’re eighteen or even twenty-six. The only way this actually works in a positive way is also out of ego, when, say, Joe or Brad comes up with a riff and I think, fuck, that’s great, and I want to try and top it by reversing the melody or writing a lyric that will blow everybody away.

Joe and I are opposites in many ways . . . and that’s what fueled our creativity. So I knew if we were going to run like that, it would inevitably cause a lot of tension. The friction between us started almost immediately—when Aerosmith played their first gig, at Boston’s Nipmuc Regional High School, on November 6, 1970. We’d barely gotten through the first number when I began shouting at him. “Turn your fucking amp the fuck down! You don’t need to be so fuckin’ loud!” I couldn’t hear myself singing. I can’t sing in the key of the band if I can’t hear my voice. I need to hear my voice over the music to know if I’m in tune. Truth is, the energy was so

there

with the band, it didn’t matter whether I heard myself or not. That was a private inside joke between me, myself, and I. I came from the club days before monitors and held my finger in my ear so I could hear myself. Like my dad says: “If you have bad ears . . . I sound pretty good.”

I’ve had constant blowups with Joe about how loud his amp is. Remember in

Spinal Tap

when Nigel Tufnel shows the rockumentary director the

11

setting on his amp? Well, my guitar player definitely had his amp turned up to 12! I tuned Joe’s guitar for him way back then because his ears were already damaged by the volume. They’re still shot. Joe’s had tinnitus for years. What he hears most of the time is a high-pitched whine.

You want opposites in a band, that’s what makes the big wheel turn and the sparks fly . . . but when you have such widely differing personalities there are going to be some upsetting exchanges. Joey told me about the time we were on Newbury Street at Intermedia Studio. Joey was on one side of the street and Joe was walking on the other side. Joey crossed the street to be next to Joe and said, “Hey, Joe, how ya doin’? Can I walk with ya?” He was full of that

wow and wonder

of recording our first album and just plain being Joey Kramer, who happens to have the biggest heart in the band. And Joe says, “Yeah, sure.” Pause. “So, Joe,” Joey asks him, “why can’t we be friends?” And Joe doesn’t even pause before he fires back, “Why? Just because we’re in a band, we gotta be friends?” Which was pretty harsh. Now, Joe may say today, “Well, I was just fuckin’ with him!” Really? Well, there was a lot of wounded silence hanging there as Joey walked away. He never forgot it.

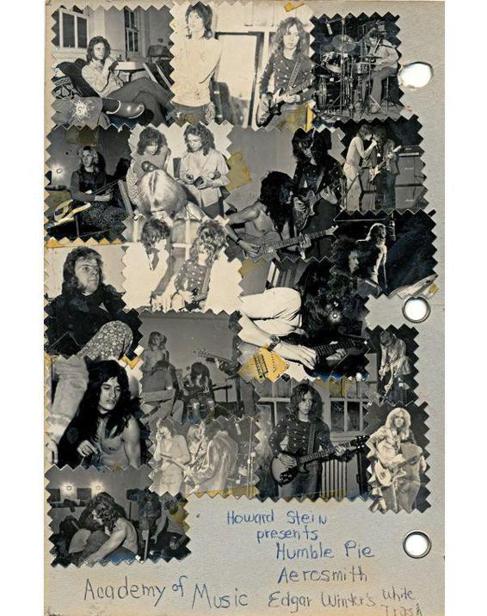

O

ur first tour book. . . . I put this together from this show in 1972. (Ernie Tallarico)

In a group it’s always about “who the fuck

you

think I am” because it’s all mental, it’s all

attitude.

If you’re scared of the dark, then the devil’s going to come out of that blackness. If you’re afraid of the ocean, you’re going to feel like something bit you on the toe. That isn’t to say that if you’re

not

afraid of the ocean, you won’t get eaten by a shark.

A

t the beginning of December 1971 we got booked into the Academy of Music on Fourteenth Street in New York, third on the bill with Humble Pie and Edgar Winter’s band. We packed all our gear in a bus and headed down there. We had no bass amps—we borrowed some to get on that stage and play. Steve Paul was the promoter. He managed the Winter Brothers, the two albino blues musicians from Texas, Johnny and Edgar. Johnny had just got out of rehab that night, but at that time Edgar was the bigger Winter. The Academy of Music was the biggest gig we’d had, where I’d seen the Stones some years before.

Right before the Stones came onstage, I could see Keith’s boots and the high heels and I knew it was them and I just about fucking wet my pants. I was freaking, the audience was screaming, the lights were down, but you could see those boots. Then, years later, I’m sitting with Keith, shortly after his father died, at Dick Friedman’s house (he owns the Charles Hotel on Martha’s Vineyard) and we’re smoking cigars, discussing life and shit. Talk about surreal, I felt my mind going back to that very Stones show and the image of those boots.

Anyway, I’m backstage at the Academy going, “Oh, my god!” On top of which Steve Paul was considering managing us. I knew Steve from his club, the Scene, on Forty-sixth Street. I played at the Scene with the McCoys, Rick Derringer’s band. Derringer was backstage at the Academy of Music tuning his own guitar by doing a method called “Octaves.” You hit an E octave up and you get a harmonic, and when it stops

waving,

then you’re in tune. I called the guys over. “Joe, Brad—you gotta see this! It’s a way of tuning without me using the harmonica.” I’d spent the last two years tuning the guys onstage with an E harmonica in my mouth. I would tune Joe’s E string and they’d try and take it from there. Now the guys could tune their own guitars. Bloody hell! Genius. I saw Derringer play live at Klein’s department store in Yonkers in like ’67 or ’68 doing “Hang On Sloopy.” He had to have been sixteen years old. I was dazzled to death.

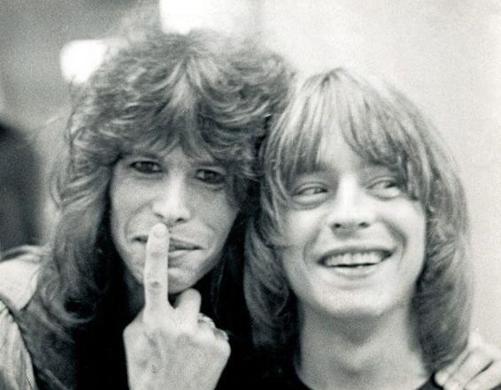

M

e and Rick Derringer backstage at the Academy of Music, 1973. “Hang on, Sloopy.” (Joe Perry)

That night we were an opening act. We were meant to play three songs and get off. We did all originals: “Make It,” “One Way Street,” and “Major Barbara.” For whatever reason, on “Major Barbara” Joe and I decided to sit down and play.

We weren’t sure of really anything except making an impression and getting our songs right. The audience started chanting, “We want Edgar!” so I butted the songs up so close together; that way the crowd didn’t have time to heckle us. We shouldered on and jammed. If we stopped playing for twenty seconds, we’d get a loud “BOOO” from the crowd. It didn’t feel good. “Major Barbara,” a song we’ve never released, had gone over quite well—no boos, just a couple of shouts. Under that kind of pressure you don’t know what you’re doing . . . you just go with whatever you have and try not to give a shit, which we did. So we just launched into “Walkin’ the Dog.”

We could see Steve Paul in the wings getting apoplectic. “Get them off!” But we continued on and finished our set. As we got off the stage, Steve Paul pulled me to the side of the stage and gave me a lobe full. “Don’t you

ever

sit down at a show that I book!”

Years later I was out at Steve Paul’s house with my first wife, Cyrinda. “I have to tell you something, Steven,” he said. “If it hadn’t been for that stupid stunt where you and Joe sat down on the stage during ‘Major Barbara,’ I’d have become your manager.” Joke’s on you, Steve! Looking back, it was a ballsy thing to do . . . sitting down. Nowadays, you call that an acoustic set. Unplugged. We just sat down so Joe could play slide on his guitar. It was very ahead of its time. And Joe played a great slide.

The apartment at 1325 was on the second floor, so when we came back from a gig we’d hump all our shit up the stairs. One night as we were unloading, I spotted a small suitcase lying against a telephone pole. I looked around, no one was there, so I snuck it upstairs real quick. Inside was a lot of dirty laundry, an ounce of pot, and eighteen hundred dollars. Wow! I grabbed the pot and the cash and took the suitcase back down and put it back in the spot where I found it. “No one will

ever

think I took it,” I told myself. There was no one else around, but obviously someone was going to come looking for this stuff. And they weren’t going to think it was the little old lady on the fifth floor who took it. Had to be the guys in Aerosmith unloading their van.

I took the cash, bought an RMI (Rocky Mountain Instruments) keyboard, and took it out on the road. I worked up “Dream On” on it and played it at our next gig. You know, the Sheboo Inn or whatever it was—the Fish Kettle Inn or the Fish Kitten Inn.

Eventually two thuggish guys showed up and demanded the suitcase, the money, and the pot. They had guns. Fuck! What now?! Out of the basement comes our biker super (and first security guy), Gary Cabozzi . . . who was something of a maniac, not to mention HUGE. Toothless, bald, 350 pounds of fucking flaming angry I-talian quivering flesh who would be delighted to kick the shit out of anyone who came near the band for whatever reason, waving a Civil War saber. “I’ve already called the cops,” he says to the thugs. “So get out of here. The cops will be here any minute.” And the guys put their guns down and ran . . . never to be seen again.

We were going to follow our quest to the bitter end, but by December of 1971 we were pretty much at the end of our tether and of everything else, too. No money, no food, no gigs, nowhere to rehearse, and nineteen dollars in the bank. I’m always one for taking things to the wall, but occasionally you actually

hit

the wall. We were at a dead end, our last gasp—and then we got an eviction notice. And just at that moment an angel appeared unto us in the form of a well-connected Irish promoter named Frank Connally.

O

ur first billboard, Kenmore Square, Boston, 1972. (Steven Tallarico)

Through a guy who played in a local band, we heard about a rehearsal space at Fenway Theater on Massachusetts Avenue. John O’Toole was the manager there and gave us our first big break when the hard rock group Cactus canceled because of a snowstorm, and we filled in for them. John O’Toole put us in touch with Frank Connally, who had brought the Beatles, Hendrix, and Led Zeppelin to Boston. Frank was connected to the movers and shakers of Boston, and he believed in us in an epic way—in the same way we believed in ourselves. To wit that, as unlikely as it seemed at the time, we would become the greatest rock ’n’ roll band in the world. And, as future superstars, he gave us a salary—a hundred a week each.

Frank wanted us to do it all over again. At first I was a little pissed off because I’d spent the last five years playing every club in New York and Long Island. But Frank knew that this new band was going somewhere, so he got us to play this new club in Massachusetts for a month to hone our chops and build a buzz.