Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (12 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

We’re polar twins. We’re total opposites. Joe is cool, Freon runs in his veins; I’m hot, hot-blooded Calabrese, a sulphur sun beast, shooting my mouth off. JOE’S A CREEP . . . I’M AN ASSHOLE. He’s the cowboy with the brim of his ten-gallon hat pulled down, the

Hell-it-don’t-matter-none

dude. But goddammit, is he always going to win? Am I always going to be the one with egg on my face? Of course, contrariness is the way the great duos have always thrived. Mutt and Jeff, Lucy and Desi, Tom and Jerry, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Shem and Shaun, Batman and the Joker.

Right off, there was teeth-grinding competitive antagonism. The internal combustion engine that drives us. It’s in our DNA, part of our chemistry. The two-way thing going on . . . combination of the two. When I met Joe, I knew I’d found my other self, my demon brother . . . the schizo two-headed beast. Joe comes up with a great riff and immediately I think, “You fuck, I gotta top that motherfucker. I’m gonna write words that’ll burn up the page as soon as I lay them down!”

But you know what? Antagonism, pure nitro-charged agro, fuels inspiration. Do I have to explain these things to you? And you can’t control animosity, can you?

We’ve been chained together for almost forty years, on the lam, like Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis in

The Defiant Ones.

Writing songs together, living next door to each other, touring, sharing girls, taping, getting high together, cleaning up together, splitting up . . . getting back together. There

is

a love there, no matter what. As soon as the anger gets resolved, we’re bosom buddies, nothing can ever drive us apart, but something inevitably comes up and I say, “Whoa! Wait a fuckin’ minute!”

Nobody can make me as crazy as Joe. No one drove me to the coffin for a reminder of

the pied piper dream

more often than Joe. Not ex-wives, not ex-managers—and you

know

how mad they can make me. Joe Perry is fucking Joe Perry—nothing I can do about that. Nothing I want to do about it. If he walked out onstage covered with vomit and shit and a needle hanging out of his arm, people would still applaud him and scream because he does the guitar god better than anyone. He’s the real deal. Not that the real deal is always the best deal.

Also the doomed, self-destructive rock star thing . . . straight out of the old

Rock Star Handbook.

Which is why I’ve got to keep my eye on him. Someone has to! Women love him; they have to live with his shit, his sniveling, smoking, and doping too much. I see him from the outside. Joe fucking Perry is the ultimate . . . but I’m the one who can see the shadow over, under . . . and inside him.

And there

is

a fucking Cloud of Doom passing over his head. My relationship with Joe is complex, competitive, fraught, really sort of fascinating in a hair-raising kind of way. There’s always going to be an undercurrent, ongoing tension, periods of homicidal hostility, backstabbing jealousy, and resentment. But hey, that’s the way the big machine works.

We’d joined that illustrious company of brawling blues brothers: Mick and Keith! Ray and Dave Davies! The Everly Brothers! That’s us, the Siamese fighting fish of rock! Aw

right

! Bring it on.

But whatever happens, when we go on tour it fuses us together, we become the big two-headed beast. I

see

Joe every night and I go, fuck, that’s it, I get it! This is why we do it! And why I

love

it. Everything kind of washes away.

All

of that.

After that night, the Rattlesnake Shakedown, I was ready to make it happen. Tom and Joe were still in high school when I first met them, thinking about going to go to college. I had already burned my boats. I was never going back. I said to myself,

Fuck it, I’m going to take a chance and move in with everybody.

Now, I knew we could do it. I loved sixties music; Brit rock stars were the shit. I wanted that sound so bad. And almost as much as I wanted the band, I wanted that lifestyle. I wanted it more than anything.

I could taste it.

The band was going to be the sixties Mach II . . . the Yardbirds on liquid nitrogen.

We’d all move to Boston and get down to the serious business of becoming famous. We had everything else, now all we needed was the fame to go with it. And being that I’m a little more crazed than most people, once I saw the light, I went for it hell for leather. My bags packed, at the end of that summer I said good-bye to my mom and dad, going, “Okay, here we go, this is the shit.”

T

he day we drove down—and here you have to stretch out the syllables—

d-r-o-o-o-o-ve

down to Boston from New Hampshire, I remember looking out the window at the trees and hills rolling by. I was feeling a little pensive (for me). I was a bit anxious about moving in with everybody; but at the same time I was ecstatic. It was a

good

anxiety, nervous and excited at the same time. And just then, the highway opened up—right at the junction, right at that spot on the highway where you see the skyline of Boston, and you go, “

What!?

” Because it suddenly goes from trees, woods, and crickets to cars flashing by and skyscrapers and apartment buildings. . . . Just at that moment, I went, “Oh, shit,

the city

!” I was sitting in the backseat. I grabbed a box of tissues from the back window of the car and asked if anyone had a pen and started to write on the bottom of the Kleenex box.

I’m in my bubble in the car. It’s like a projection booth where I’m screening our future on the windshield, a wide-screen movie of coming attractions—I can see it! Joe’s Les Paul gnawing through reality like a sonic shark, little pop tarts throwing their panties onstage, the high of fusing twenty thousand people into your own fantasy. The car’s moving (it’s also in the movie) . . . images and words colliding, generating a kind of spell of what I wanted to happen.

At the moment that I saw the Boston skyline, words began flooding into my head:

Fuck, we gotta make it, no, break it, man, make it. We can’t break up, we gotta make it, break it, make it, you know, make it.

And I began writing:

“Make it, make it, make it, break it,

” saying the words over and over to myself as I wrote them, like a prospector panning sand in a stream, back and forth and back and forth—water and sand, water and sand—until a little nugget emerges out of the sand. And there in the back of the car I thought to myself,

What would I fuckin’ say to an audience? If we write songs, get up onstage, I’m gonna be looking the audience in the eye, and what am I gonna say? What would I want to say?

I’m starting to pan for the gold:

What do I say? What would I want to say? What’s cool to say?

All those ideas were beginning to gell into one fuckin’ phrase. . . . Whoops, here we go!

Um . . . good evening, people, welcome to the show . . .

[First-person, me singing to the audience . . . ]

I got something here I want you all to know . . .

[The collective we, the band . . . ]

We’re rockin’ out, check our cool . . .

[Um, no, no, that’s no good, uh, talk about my feelings . . . ]

When life and people bring on primal screams,

You got to think of what it’s gonna take to make your dreams,

Make it . . .

Oh, fuck yeah! Now I’m scribbling like crazy on the Kleenex box.

You know that history repeats itself

But you just learned so by somebody else

You know you do, you gotta think the past

You gotta think of what it’s gonna take to make it last;

Make it, don’t break it!

Make it, don’t break it! Make it!

And there it was, first song, first record. Put that in your pipe. . . .

My Red Parachute

(and Other Dreams)

I

’ve been. . .

New Orleaned, collard-greened, Peter Greened and tent-show queened; woke-up-this-mornin’ed and givin’ you a warnin’ed, Seventh Sealed, cotton field; holler-logged and Yeller Dawged; sanctified, skantified, shuck-and-jived, and chicken-fried; black-cat boned, rollin’ stoned, and cross-road moaned; freight-trained, achin-heart pained, gris-gris dusted, done got busted; bo-weeviled, woman eviled; mojoed, dobroed, crossroad, and mo’ fo’ed; share-cropped and diddley bopped, Risin’-Sunned and son-of-a-gunned; voodooed, hoodooed, and who do you’d; red-light-was-my-minded and baby why you so unkinded; Mississippi mudded and chicken-shack flooded; boogie-woogied, Stratocasted, blasted and outlasted; 61 Highwayed and I did it my wayed; Little-Willie-Johned and been-here-and-goned; million-dollar riffed and Jimmy Cliffed; cotton-picked and Stevie Nick’d. . . .

The blues, man, the blues . . . the

blooze!

That achin’ ol’ heart disease and joker in the heartbreak pack, demon engine of rock, matrix of über-amped Aerosmith, and the soul-sound of me, Steven Tyler, peripheral visionary of the tribe of

Oh Yeaah!

Now the blues is, was, and always has been the bitch’s brew of the tormented soul. The fifth gospel of grits and groan, it starts with the first moan when Adam and Eve did the nasty thing and got eighty-sixed from the Garden of Eden.

“Once upon a time . . .” “In the beginning was . . .” That’s the way it always starts off. Every story, gospel, history, chronicle, myth, legend, folktale, or old wives’ tale blues riff begins with “Woke up this mornin’. . . .” The blues is soiled with muddy water, funky with Storyville whorehouse sweat and jizz, smoky from juke-joint canned heat, stained with hundred-proof rotgut and cheap cologne. It’s so potent ’cause it’s been in every low-down, get-down joint the world has ever seen.

Everybody sucks on someone’s tit, and ours was the bitch’s brew of the blues.

M

y first sexual musical epiphanies came through the radio. They were all entangled together. I can’t remember how old I was when I first realized they were separate things—but

are

they? That’s the question. I used to listen to the radio as if these sounds and voices were coming from outer space. Deejays were magicians who talked to you through the air somehow and brought you these erotic sounds, songs about love, desire, jealousy, loss, and sex. Later on I’d listen to 1010 WINS, which was a New York rock station back then, and hear all these great crazy characters talking that buzzy deejay jive talk.

When I moved with the band at the end of 1970 to Boston, it had the greatest rock ’n’ roll stations of all time, and believe me I heard them all. Radio at its finest.

When Aerosmith was just starting out I began dating a very sexy deejay at one of those stations. I’d never known an actual disc jockey before, but I knew they were famous people who could get you famous—and thus get you laid. But until I met her I didn’t know you could do both . . . on the air.

Of course me being in a band and trying to make it in Boston, what better thing than to be over there on the air making out with her while she was doing the dog and cat reports—that’s when they announced the missing pups and pussies. She didn’t have prime-time spotage so she had to do a lot of public service spots: the community center is having a dance; the local synagogue is throwing a picnic.

It was hilarious the things I did to that woman while we were on the air just to see if I could rattle her cage. I never really did. It was funny, though; we did the most incredible things. I’d give her head while she was on the air, take off her panties and have her sit on my lap and fuck her.

Such outrageous stuff, and we got away with it! Nobody knew, but let me tell you what . . . she got rave reviews! Not only were we getting very, very high—I was shoveling spoonfuls of coke under her nose—but we were really climbing under the covers, so to speak. All this while she’s playing Led Zeppelin, Yardbirds, Animals, Guess Who, Montrose, Stones—tons of great shit. It was a graveyard shift, but regardless of what it was, big or small, we were still live on the air, and it makes you just want to test the water and see what you can get away with. I used to do shit like sing along with records—people didn’t know that I was doing it, they must have thought she was playing some outtake or live track. I’d tell jokes, recite limericks, make up bizarre news items. God, that was heaven!

I would be all over the place: early Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green, Blodwyn Pig, Taj Mahal, the Fugs. In those days deejays would play the whole side of an album. Nowadays some of your best XM/Sirius stations play deep tracks. We should all be proud that our music, what they were inventing back then, has lasted so long. Love—and the music of its time—is its own reward isn’t it? And having sex with the deejay while she’s playing “Whole Lotta Love” was the ultimate consummation of my radio sex music fantasy.

J

oe Perry, Joey Kramer (we went to the same high school in Yonkers), Tom Hamilton, and I arrived in Boston and got an apartment at 1325 Commonwealth Avenue in the fall of 1970, entering the city like spies, ready to conquer the world overnight. It took a little bit longer than we thought it would.

With any of the bands I’d been in I’d always wished we could live together. I’d been dreaming of that since I was twelve, and now we could. We could write together, go to bed at night with the lick we wrote that afternoon fresh on our minds. The Island of Lost Boys.

Day one, I said to the guys, “This is so great that we’re living together! I fuckin’ love that!” It started out blissfully but soon turned into little skirmishes over chewing gum and toothpaste and petty psychological feuds. But that’s what marriages are. And in the end the band really worked, and I think somewhere deep inside—and quite hidden even from themselves!—they really loved me for making them do that when we lived at 1325. Stealing the food and cooking! I would make breakfast; we’d learn those songs and really craft them, make them tight.

In his book,

Hit Hard: A Story of Hitting Rock Bottom at the Top,

Joey told the world that the reason he has a facial tic is that I abused him just like his father did. I used to yell at him. I’d say, “Don’t play it like that . . . play it like this!” I know good things don’t come without practice; if I was hard on him it was because we had to get it right. But because I had decided not to be the drummer in the band, I gained a right IN MY MIND to be able to live vicariously through Joey.

I had a dream. So in the beginning, Joey was my interpreter, and we sat and played together. I took my drum set and said, “Joey, today’s the day.” And he’d go, “What, man?” And I’d go, “Well, you set up your drums and I’ll set up mine . . . right in front of you! And we’re gonna play facing each other.” He never understood. Later on, with Aerosmith records, he always thought that if I did a snare hit with him—or if I played the high hat while he played the drums—people would notice that there was someone else playing the drums. And I’d say, “Listen to Greg Allman’s ‘I’m No Angel’ or the Grateful Dead stuff with two drummers. It’s a

sound.

The Beatles sang in a room that had a voice . . . which means the room had an echo. They didn’t have some ass fuck engineer try to get rid of it. They put it on the track like that. Once it’s a hit, that echo is on there forever.”

A room has its own sound and music. You can buy a machine and tune it to “ambience.” When we were making

Just Push Play,

we recorded our empty room. If you record that hall noise and sing over it, it’s like letting the hall embrace you. It has chairs and equipment and people. The room IS another instrument. The room is in the band.

So with Joey, we would play together, and in the beginning—what I’m getting at—is there’d be this Cheshire grin on both our faces. He loved me and I loved him. He couldn’t believe the tricks I knew. And to this day, he can play what I could never play. But back then, in ’71, it was all about “Hey, show me

that

again!”

Hence there was I, night after night, sitting near his drum riser, going, “Do a drum fill here,” ’cause he really didn’t know on his own that after the second verse—right after the prechorus, going into a chorus—one needs something exciting and . . . what would that be, Mr. Drummer?

A drum fill!

A prechorus means “Whoops, here it comes.” A verse should be the storytelling, and the prechorus is the “Whoops, here it comes.” And then a drum fill to go into it to show that it’s

important . . . to mark its importance!

End of the song, maybe a prechorus again, and a middle eight (recapitulation), a little “tip o’ the hat” to something you might have said in the beginning of the song to remind everybody what it was about . . . and WHAMMO, right into your chorus and you’re out. And during the chorus and the fade . . . come on, play the drums even more. These things I knew and learned and passed on to Joey. So he played, and for the last thirty-five years, I lived

through

him. I don’t know how

not

to.

You know what one of my favorite albums of all time is? Stevie Wonder’s

Songs in the Key of Life,

mainly because of what drummer Raymond Pounds decided to do, which was, in essence,

not

live up to his last name. There are very few drum fills on that amazing record. You can be good just holding down the fort. On Zeppelin’s “Kashmir,” listen to that drum beat. Simple. Straight. It gives the song legs—like the linemen who protect the quarterback.

Since I’m a drummer and a perfectionist, I rode Joey hard, admittedly. But in the process I made him a better musician. Like when we’re sound checking in Hawaii, I sat down at the drums and wrote the drum line for “Walk This Way.” You want the story now or when we get to

Toys in the Attic

? Hey, I never said this was gonna be a completely linear read. How could it be? (Ha!) But we’re on DRUMS so . . . what the fuck?

One of the things I’m most proud of is “Walk This Way,” and it’s very

EGO

and all, but even after you read the press about Run DMC and Rick Rubin, I still think the song was a HIT in and of itself. And the proof of the pudding . . . “

Backdoor lover always hiding ’neath the covers.

” You can’t SING that unless you’re a drummer or have some major sense of rhythm.

B

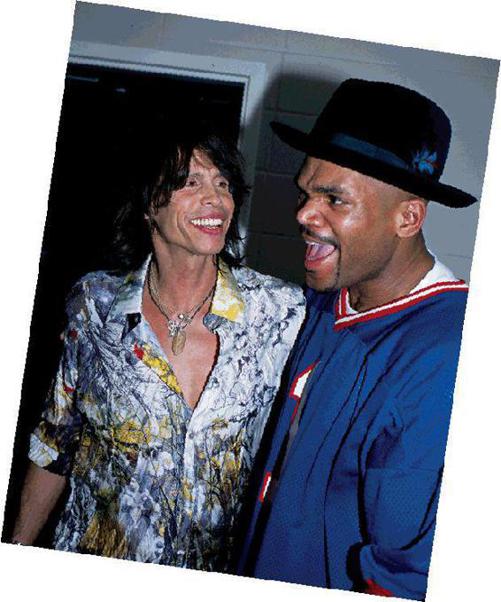

ackstage with Darryl (Run-D.M.C.) in 1982. (Ross Halfin)

So we’re at the HIC Arena in Honolulu, doin’ a sound check, and Joe was playing a riff and I went, “Whoa, whoa, whoa . . . STOP!” I ran over to the drums. Joey had not come out yet. He was backstage, and Joe and I just started jamming on the “Walk This Way” riff ’cause Joe’s rhythm was fucking “get it!”

Bada da dump, ba dada dump bump (air) . . . bada da dump, ba dada dump bump.

I got on the drums and played to

that,

and that’s where the “Walk This Way” drum beat came from.

Joey wasn’t the best drummer in the world when I joined the band, and I was a drummer, and it was my theory of how a real band rehearses that fused the band together—playing that line from “Route 66” over and over and over again—and because I wrote the song “Somebody.” Eventually Joey achieved his independence as a drummer. He always had a hard time playing the rhythm at the end of “Train Kept a-Rollin’,” but he worked on his independence—that’s your ability to move all four of your limbs independently—and in the end he’s turned into the greatest drummer in rock ’n’ roll. He now has a right ankle that’s like a bicep from playing the bass drum.

Joey says I drove him crazy, gave him a nervous breakdown. When we were in rehab together at Steps in Malibu in 1996, the class confronted me. “What’s the big idea of bringing someone here who’s an active addict?” I said, “What the fuck are you talking about?” “Your drummer, your drummer’s on cocaine, he’s got that tic addicts get from snorting coke.” Then I had to explain—but I had no idea

I

was the explanation.