Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (14 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

No one had ever played like that. No one. So imagine being in his band and saying, “We just

played

that.” Or the Stones creating that raunchy spooky blues vibe, that

energy,

that

tangible

force that could

not

be denied, it had to be reckoned with. A sound that would be the mouthpiece for a whole generation. When you think about rock bands that made it, why did they make it,

how

did they make it, what did they make it

for—

I can get really emotional about this stuff. Because the

music

that they made was so strong, so overwhelming that it was a prayer and an answer all at once.

The Beatles, come on, and what the fuck! It wasn’t because they were all such great musicians. They knew. They knew. They were English and they had long hair when nobody else did and they said funny things, but it wasn’t that, either. It was the alchemy they cooked up—Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry—and music hall numbers.

And they evolved, as did the Stones, the Who. Many groups came out, had a hit, and then took the ferry back across the Mersey. The Beatles went from “She Loves You” to “Help” within a year. In one year. Not ten. In two years they were at the trippy

Rubber Soul

. “Norwegian Wood,” how great is that? So you can say what you want, but in one year they started out recording in a room where Paul and John sang together on one mic, took that vocal and dumped it down to one track, and added it to the next vocals. You know what that means? It means you can’t go back. They had to be so sure of themselves. Plus, of course, they had George Martin as a producer.

W

e needed a name, so we all got together and tossed names around the table, like Stit Jane. I came up with the Hookers. No one liked that. “How about Arrowsmith,” Joey suggested. “

Arrowsmith?

You mean like the Sinclair Lewis novel we had to read in high school?” And then, a minute later, I went “Aero: a-e-r-o, right?” And he goes, “Yeah.” Now

that

was cool. The name evoked space—aerodynamics, supersonic thrust, Mach II, the sound barrier. I thought if we could stay together, that name would always work because we had nothing to look forward to except the future. I always imagined that when I was fifty, there’d be robots already, skateboards that floated and you could jump on. Everything that happened to me since I was ten came out of comic books anyway. All the superheroes had that shit. Every bit of it—lasers, light sabers, phones that you could talk into. Dick Tracy had that watch on his arm. He was talking to it all the time. Watching

Dick Tracy

I used to think, “What if we all had one of those watches?”—but it was just a crazy kid thought. Now everyone has one with all the apps—check your e-mail, blog, Twitter me . . . and please, sit on my Facebook.

I’d thought of calling us the Hookers because I considered playing clubs a form of prostitution—I’d spent six years playing clubs in New York and knew how exhausting and frustrating it was. So with Aerosmith we avoided the club scene like the plague. It’s a trap. The money’s okay—a thousand a week would be a nice payday—but doing four sets a night (for forty-five minutes each, even if the club was empty) for a two-week stretch playing other people’s material will grind you down. No time to rehearse, write, develop new material. People shouting “Play ‘Maggie May’!” “Hey, you fucks, know any Credence songs?” In any case we were too rowdy for most clubs and bars. We got kicked out of Bunratty’s Bar in Boston because we started to incorporate original material and the club owners didn’t like that.

Instead we focused on colleges, high school dances, ski lodges. We played around a lot, mostly weekends, rehearsing during the week. Playing high school dances out in the country, getting maybe three hundred dollars a night.

We played absolutely anywhere that fifty people would come see us. As the keeper of our gig calendar, I had to make sure we had at least three dates a month for around three hundred dollars to cover our rent and basic nut. We functioned like a guerrilla band: play a small town, establish a beachhead, develop a small fan base, next time through there’d be more kids and more and more enthusiastic fans.

Our set list was our Brit blues catechism. Real heavy metal to me is Led Zeppelin playing “Dazed and Confused.” We got our roots the same place Zeppelin got theirs—and I don’t mean from Jake Holmes, the guy who inspired Jimmy Page—I mean de blooze.

When we started out, there must have been five thousand rock ’n’ roll bands in the Boston area alone trying to make it. But if you are going to separate yourself from the pack you have to develop your own identity and you aren’t going to do that by playing other people’s songs. In the very beginning we, too, did cover versions (we only had a couple of our own songs).

We never played in our street clothes. We always dressed up . . . put on a show. You’re in a band, lads, we’ve got to get

flash

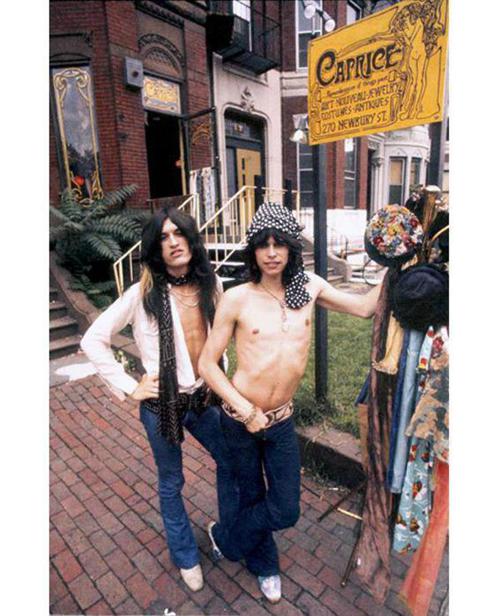

. The look is the hook. I got the band to strut their stuff, dress up, get their sartorial swagger on. I’d walk into Caprice, an antiques store on Newberry Street owned by my friend Barbara Brown. She said to come down to her store and she’d give us some clothes for our first album photo shoot. I had to ease the guys into the fashion thing. I was already having my leather pants done in flames from the girl who lived upstairs at Number 5, Kent Street. I brought the band to Caprice and told ’em to rummage around, pick their own stuff out. It was a free-for-all.

A

t Barbara Brown’s store with Joe Perry. . . . I brought the band here for clothes for the first album in 1972. (Robert Agriopoulos)

The store was opposite Intermedia Sound where we would record our first album. “Here, put this on!” I said. “Hell, no, I’m not gonna wear

that

.” “Aw, c’mon, man, just do it for the pictures! Look at the Brit art school flash! Look at Jimmy Page! Look at Mick! Look at Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck! Look at Pete Townshend! The Union Jack jacket is the shit. Are they wearing jeans and army surplus? I don’t think so.” After a lot of yacking they got into the clothes that made the picture on the first LP cover explode . . . and they looked fucking great.

That photo was taken on the stoop in front of Barbara’s store. Brad had one of her shirts on, Joey’s got her jacket, I wore the hat and the belt. That’s it, baby. We got the shot, and then some brain-dead police working at Columbia shrank it down and put clouds behind it—the beginning of my corporate hell.

We raided the closets of the hipoisie. A mad mix of King’s Road medieval motley, pimp swagger, Stones gypsy gear and Carnaby Street kitsch. Janis’s Haight-Ashbury scarf-draped bordello exotica (god, I’m getting off just saying this!) and a touch of titillating androgyny for shits and wiggles. Anything startling, garish, glam, and over-the-top: jewelry, earrings, black lace, feathers, metal flake, eyeliner. All the stuff we need to look cool and out there. Whatever it takes to spark that outlandish rock star impudence. Anything that denotes snotty, defiant arrogance and beyond-the-pale chic.

Let your freak flag fly!

And a few Aerosmith tattoos just to underline the outlaw element. Find out where they are, folks!

We were perfect for the dandified Brit look. We weren’t pumped . . . on the contrary, we were skinny and weedy, just like the English musicians. Anyway, our outfits paled beside those of the New York Dolls: hot pants, fake leopard skin, black nail polish, panty hose, bouffant hairdos, feather boas, and six-inch platforms.

Most of this band’s early career had been spent making fun of me for what I wore—clothes and shoes—and then they’d wind up wearing it themselves. I’d put jewelry on the guys in the band and there would be a comment. Joe has said to me more than once about my style or what I was wearing, “Wow, I love those pants. Do they make ’em for guys?” At first—and for a very long time thereafter—Joe was

aloof.

When I’d point out that this is the stuff Mick, Keith, and Jimmy Page wore, he’d say, “What do I want to look like him for? I’m

me.

” I just wanted to be a gypsy. Interestingly enough, whatever Joe’s own thing is, your thing, anyone’s thing, that’s it. That’s where the song “Make It” came from.

You know that history just repeats itself

Whatchoo just done so has somebody else

You know you do, you gotta think the past

You got to think of what’s it gonna take to make it last

I lifted those lyrics out of the creative ether . . . my inner voice. I live and stand by it. You’ve got to make up your own shit out of what’s already there. I always figured, “I don’t know what I’m doing, but I know I’m doing it!”

I kind of got offended when Madonna came out with her thrift shop chic like she’d invented it. That’s the way everyone dressed from 1966 to Woodstock. And then in the eighties, Madonna came out with “Material Girl” and her bangles and stuff and I went, “Yes!” Wow, what a fickle, fuckin’ mass media! Because nowadays, everything’s recycled. There’s nothing new. Everything’s in quotation marks. What

wasn’t

before? Gypsy Boots, he was the

first

nature boy, living in a tree and dressing like it’s 1969.

M

y dream had come true, but the second I said, “It’s so great that we’re all living together,” Joey moved in with his girlfriend, Nina Lausch, and Joe moved out with Elyssa. Was it my breath? We were a unit, watching the sparks fly, day or night. Didn’t they know that some of the best creative shit came in the midnight hour? In my other bands I’d seen how women led to a breakup—look at the Beatles—and I didn’t want that to happen to us. I pleaded with my

brother

. “Joe! You’re Joe

fuckin’

Perry . . . you’re the ultimate, the beyond-which-there-is-nothing—when I met you, I knew I’d found my guy. Come on now, man . . . you gotta stay. We gotta write together . . . that’s the whole reason I moved to Boston.” But to no avail.

I was angry at Elyssa because she stole my boyfriend, my significant other, my partner in crime! It was like losing a brother. So now there was jealousy, this dark undercurrent humming along. I felt that Joe abandoned me—that he cared more about Elyssa than he did about the band. After all these years, it’s okay to admit it. I was really hurt that he would rather be with Elyssa than be with me, especially after we started writing songs together. Like I said earlier with “Movin’ Out,” Joe’s sitting on the water bed and I hear him strumming this thing and I go, “Hold on . . . whoa, what’s that?” and a minute later, Joe’s riffing and I’m scribbling . . .

We all live on the edge of town

Where we all live there ain’t a soul around

And it was in the afternoon, and that song wouldn’t have happened unless we’d been living

together.

Writing songs

was

fucking. I took my anger and jealousy and eventually put it into “Sweet Emotion,” which I pointed at Elyssa directly . . .

You talk about things that nobody cares,

You’re wearing out things that nobody wears

Calling my name but I gotta make clear

I can’t tell ya honey where I’ll be in a year

I used my jealousy and anger for lyrical inspiration. Looking back, I’m actually grateful that Joe moved out with Elyssa. It gave me something to sing about, a bittersweet emotion. My relationship with Joe is fraught to say the least. Even in the best of times we sometimes don’t speak for months. On tour we’re brothers, soul mates, but there’s always an underlying tension broken up by moments of ecstasy and periods of pure rage.