Dinosaurs Without Bones (75 page)

Read Dinosaurs Without Bones Online

Authors: Anthony J. Martin

FIGURE12. Field photograph documenting the discovery of the first known dinosaur burrow and the ornithopod dinosaur that made it,

Oryctodromeus cubicularis

. The sandstone spiraling down from the reddish mudstone outlines the burrow, and the plaster jacket surrounding the dinosaur bones also shows the approximate location of the burrow chamber. (

Photograph by David Varricchio.

) Brush (upper left) = 2.5 cm (1 in) wide.

FIGURE 13. Field perspectives of excavated dinosaur burrow attributed to

Oryctodromeus

,

preserved as a sandstone cast of the original burrow: overhead view (top) and side view (bottom). The burrow chamber was cut off from the main “tunnel” when the plaster-jacketed bones were recovered from the site. Notice also the small burrows coming off the right-hand corner and left-hand corners of the main burrow, interpreted as coming from commensal animals. Scale = 15 cm (6 in).

FIGURE 14. Comparison between Late Cretaceous dinosaur burrow from Montana (left)

and purported Early Cretaceous dinosaur burrow from Victoria, Australia (right). Each had a coarser sediment fill (pebbles), although only the Montana one contained bones and had commensal burrows. Both burrows at the same scale, scale bar = 50 cm (20 in).

FIGURE 15. Borings in Late Jurassic dinosaur bones, attributed to bone-boring termites. Obviously, these trace fossils were made after the dinosaur was already dead. Specimen is about 15 cm (6 in) wide, and is on display at Dinosaur National Monument (Utah).

FIGURE 16. Toothmarks in an

Apatosaurus

ischium, which, based on their sizes and spacings,

were probably made by the large theropod

Allosaurus

. Specimen is on display at Dinosaur Journey Museum (Museum of Western Colorado), Fruita, Colorado; scale in centimeters.

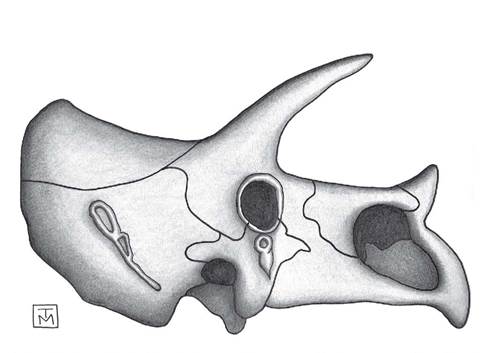

FIGURE 17. Right side of a

Triceratops

skull with wounds on its squamosal (left) and jugal (center) bones, a trace fossil of where another

Triceratops

collided with it. Sketch informed by figures and descriptions by Farke

et al.

(2009).

FIGURE 18. The Late Cretaceous hadrosaur

Edmontosaurus

(top), with a

Triceratops

skull

for scale, and a close-up of its tail bones (bottom) with a healed bite mark. The latter is a trace fossil of a theropod attack that the hadrosaur escaped (lucky for it, unlucky for the theropod).

FIGURE 19. Possible dinosaur gastroliths, or just rocks? A dilemma posed by smooth,

rounded, and polished stones in many Mesozoic sedimentary formations made while dinosaurs were alive. Specimens are on display at the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum in Price, Utah.

FIGURE 20. Gastroliths that were formerly in the abdominal cavity of an Early Cretaceous marine reptile, with a partial rib included. Specimen at Kronosaurus Korner in Richmond, Queensland, Australia.

F

igure

FIGURE 21. A mass of small gastroliths in the abdominal cavity of the Early Cretaceous

theropod

Caudipteryx

from China. Specimen is a replica (cast) of the original and is on display in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.