Dinosaurs Without Bones (74 page)

Read Dinosaurs Without Bones Online

Authors: Anthony J. Martin

viviparity (live birth),

91

W

wide gauge trackways,

29

wood-boring insects,

254–55

,

322

Wyoming Dinosaur Center,

50

Y

Yellowstone National Park (Wyoming),

357–58

Z

zygodactyl,

307–9

FIGURE 1. An imagined Cretaceous landscape devoid of dinosaurs, but filled with their traces, some of which later became trace fossils.

FIGURE 2. Known trackway patterns of some dinosaurs, including (top, left to right) theropods, ornithopods, sauropods, ankylosaurs, and ceratopsians; examples of trackway patterns (bottom, left to right) made by a Middle Jurassic theropod (Wyoming), an Early Cretaceous sauropod (Texas), and Late Cretaceous ornithopods (Colorado). The ornithopod tracks show both bipedal and quadrupedal movement by their makers.

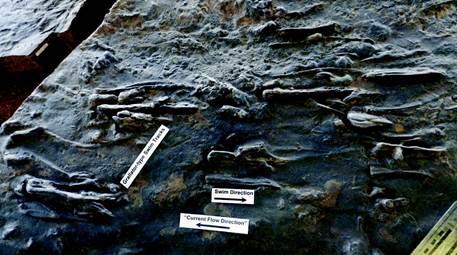

FIGURE 3. Swimming dinosaur tracks from the Early Jurassic of Utah. These were probably

made by theropods that swam from left to right against the current flow, with their claws digging into the bottom. The tracks were later filled in with sand, which made natural casts of the tracks. Tracks on display at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, St. George, Utah. Scale (lower right) in centimeters.

FIGURE 4. Parallel and evenly spaced Late Jurassic sauropod trackways, showing probable herding, at the Purgatoire River tracksite near La Junta, Colorado. (Notice how the people seeing these tracks can’t help but walk along them, stand and stare at them, or simply sit in them.)

FIGURE 5. Panorama of the Lark Quarry tracksite in Queensland, Australia. Nearly every

dent on the rock surface is a dinosaur track, a small sample of the nearly 3,000 Late Cretaceous footprints preserved there.

FIGURE 6. Close-ups of the three-toed dinosaur tracks at Lark Quarry, with the largest one (top) from a large theropod or ornithopod, and the smaller ones also either from theropods or ornithopods. Note how most of the small ones are pointing the opposite direction of the big one. Why?

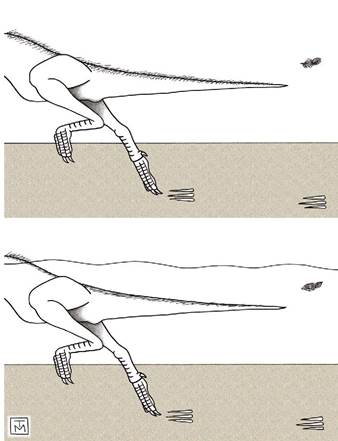

FIGURE 7. How a running theropod (top) and swimming theropod (bottom) of the same

size could have made tracks looking like those in Lark Quarry.

FIGURE 8. Hypothetical dinosaur trackway patterns associated with sex, such as from bipedal theropods (left) and quadrupedal sauropods (right).

FIGURE 9. Late Cretaceous insect cocoons in rock (center, lower right) that was part of a

Troodon

nest (Montana). The cocoons likely belonged to burrowing wasps that lived in the soils on and around the dinosaur nests.

FIGURE 10. Late Cretaceous

Troodon

nest structure (Montana), artistically reconstructed and with egg clutch in center (left), and Late Cretaceous titanosaur nest structure from Argentina with only part of its original egg clutch (right). Both nests at the same scale, scale bar = 50 cm (20 in).

FIGURE 11. Right rear-foot anatomy of a sauropod suspended above a track, showing how

its anatomy corresponds with the track below it (left); digging motion needed by rear foot to make nest (right). Foot and track part of a display at Dinosaur Valley State Park (Texas), and diagram informed by Vila

et al.

(2010) and Fowler and Lee (2011). Scale bar (left) = 10 cm (4 in).