Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (34 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

2.26Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In 1600, in fact, ordinary folks anywhere in this world would have assumed that the Muslim empires and their adjacent frontier territories were in fact “the world.” Or, to quote University of Chicago historian Marshall Hodgson, “In the sixteenth century of our era, a visitor from Mars might well have supposed that the human world was on the verge of becoming Muslim.”

9

9

The Martian would have been mistaken, of course; the course of history had already tipped, because of developments in Europe since the Crusades.

11

Meanwhile in Europe

689-1008 AH

1291-1600 CE

1291-1600 CE

T

HE LAST CRUSADERS fled the Islamic world in 1291, driven out by Egypt’s mamluks, but in Europe residues of the Crusades persisted for years to come. Some of the blowback came from those military religious orders spawned by the Church of Rome. The Templars, for example, became influential international bankers. The Knights Hospitaller took over the island of Rhodes, then moved their headquarters to Malta, from which place they operated more or less as pirates, looting Muslim shipping in the Mediterranean. The Teutonic Knights actually conquered enough of Prussia to establish a

state that lasted into the fifteenth century.

HE LAST CRUSADERS fled the Islamic world in 1291, driven out by Egypt’s mamluks, but in Europe residues of the Crusades persisted for years to come. Some of the blowback came from those military religious orders spawned by the Church of Rome. The Templars, for example, became influential international bankers. The Knights Hospitaller took over the island of Rhodes, then moved their headquarters to Malta, from which place they operated more or less as pirates, looting Muslim shipping in the Mediterranean. The Teutonic Knights actually conquered enough of Prussia to establish a

state that lasted into the fifteenth century.

Meanwhile, Europeans kept trying to launch new campaigns into the Muslim world too, but these were ever more feeble, and some dissipated along the way, while others veered off on tangents. The so-called Northern Crusade ended up targeting the pagan Slavs of the Baltic region. Many little wars against “heretical” sects within Europe, whipped up by the pope and conducted by this or that monarch, were also labeled “crusades.” In France, for example, there was a long “crusade” against a Christian sect called the Albigensians. Then there was Iberia, where Christians kept on crusading until 14

92, when they overran Granada finally and drove the last of the Muslims out of the peninsula.

92, when they overran Granada finally and drove the last of the Muslims out of the peninsula.

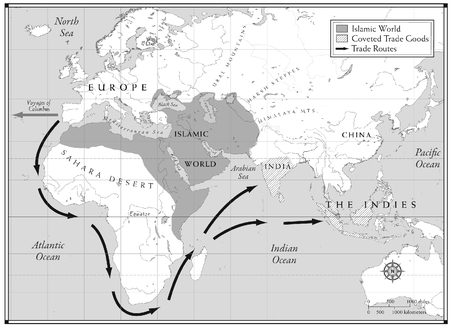

The crusading spirit persisted in part because over the course of the real crusades, a new motivation had entered the drive to the east: an appetite for trade goods coming from places like India and the islands beyond them, which Europeans called the Indies. One of many desirable goods to be found in India was an amazing product called sugar. From Malaysia and Indonesia came pepper, nutmeg, and many other spices. Chefs of the High Middle Ages put spices in everything they cooked—often the same spices in savories and desserts; they just liked spices!

1

1

The trouble was, the Crusades stoked an appetite for the goods but also separated European merchants from those goods by creating a belt of anti-Christian hostility that stretched from Egypt to Azerbaijan. European businessmen couldn’t get past that wall to trade directly with the source: they had to deal with Muslim middleman. It’s true that Marco Polo traveled to China in this period, but he and his group were just one anomalous band, and Europeans were amazed that they had made it all the way there and back. Most, in fact, didn’t believe he had really done it: they called Marco Pol

o’s book about his adventures “The Millions,” referring to the number of lies they thought he had packed into it. Muslims owned the eastern shores of the Black Sea, they owned the Caucasus mountains, they owned the Caspian coastline. They possessed the Red Sea and all approaches to it. Europeans were forced to get the products of India and the Indies from Muslim merchants in Syria and Egypt, who no doubt jacked the prices up as high as the market would bear, especially for their European Christian customers, given the ill will from all that happened during the Crusades, not to mention

the fact that the Farangi Christians had aligned themselves with the Mongols.

o’s book about his adventures “The Millions,” referring to the number of lies they thought he had packed into it. Muslims owned the eastern shores of the Black Sea, they owned the Caucasus mountains, they owned the Caspian coastline. They possessed the Red Sea and all approaches to it. Europeans were forced to get the products of India and the Indies from Muslim merchants in Syria and Egypt, who no doubt jacked the prices up as high as the market would bear, especially for their European Christian customers, given the ill will from all that happened during the Crusades, not to mention

the fact that the Farangi Christians had aligned themselves with the Mongols.

What were western Europeans traders to do?

This is where the crusading spirit bled into the exploring impulse. Muslims straddled the tangle of the land routes that connected the world’s important ancient markets, but over the centuries, unnoticed by Muslim potentates and peoples, western Europeans had been developing tremendous seafaring prowess. For one thing, Europeans of the post-Crusades era included Vikings, those invading mariners from the north who were so good at seafaring, they had even crossed the North Atlantic to Greenland in their dragon boats. One wave invaded England where the word

North-men

slurred into

Norman.

A few of these then moved to the coast of France, where the region they inhabited came to be known as Normandy.

North-men

slurred into

Norman.

A few of these then moved to the coast of France, where the region they inhabited came to be known as Normandy.

THE EUROPEAN QUEST FOR A SEA ROUTE TO THE INDIES

But it wasn’t just the Vikings. Everyone who sailed regularly between Scandinavia and southern Europe had to develop rugged ships and learn how to manage them in the big storms and high seas of the North Atlantic; western Europeans, therefore, ended up very much at home on the water. With such accomplished mariners amongst their subjects, some ambitious monarchs began to dream of finding a way to skirt the whole land mass between Europe and east Asia and with it the whole Muslim problem: in short, they got interested in finding a way to get to India and the islands further east entirely by sea.

One aristocrat who poured serious support into this enterprise was Prince Henry of Portugal (called “Henry the Navigator” even though he never went on any of the expeditions he sponsored). Prince Henry was closely connected to the king of Portugal, but more important, he was one of the richest men in western Europe. He funded sea captains to sail south along the coast of Africa looking for a way around it. Henry’s letters and proclamations show that he originally saw himself as a crusader, out to prove himself a great Christian monarch by scoring victories against the Moors and finding new s

ouls to save for the one true faith.

2

ouls to save for the one true faith.

2

Many of the new souls his sailors found were living in black-skinned bodies and had commercial value as slaves, it turned out, and Prince Henry the Navigator morphed into Prince Henry the Slave Trader. In addition to slaves, as the Portuguese made their way south, they found all sorts of other marketable commodities such as gold dust, salt, ostrich eggs, fish oil—the list goes on and on. The constant discovery of new trade goods infused the crusader’s dream with an economic motive, and the Crusades gave way to what Europeans call the Age of Discovery. Perhaps the most dramatic discovery occurre

d in 1492, when Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic, looking for a route to India, and stumbled across the Americas. His voyage was funded by Ferdinand and Isabella, the Christian monarchs who completed the Crusade against the Muslims of Iberia and founded a single, unified, Christian kingdom of Spain.

d in 1492, when Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic, looking for a route to India, and stumbled across the Americas. His voyage was funded by Ferdinand and Isabella, the Christian monarchs who completed the Crusade against the Muslims of Iberia and founded a single, unified, Christian kingdom of Spain.

When Columbus landed on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, he famously believed he had reached the Indies. After his mistake became known, the islands east of India were called the East Indies, and these islands in the Caribbean the West Indies. Most Muslims were only vaguely aware of this momentous discovery. Ottoman sources mention Columbus’s voyage in passing, although by the 1570s, a few Ottoman cartographers were creating fairly accurate maps of the world showing the two Americas right where they are in fact located. By then, Spain had built the rudiments of a new empir

e in Mexico and the English, French, and others had planted settlements further north.

e in Mexico and the English, French, and others had planted settlements further north.

Meanwhile, at the eastern end of the Middle World, Muslims had already discovered what the Europeans were originally seeking: Muslim traders had been sailing to Malaysia and Indonesia for centuries. Many Muslim traders who plied these waters belonged to Sufi orders, and through them Islam had taken root in the (east) Indies long before the first Europeans arrived.

Even before the Portuguese, Spaniards, English, Dutch, and other northern Europeans caught the exploring fever, southern Europeans were already making their clout known at sea, for their civilization had emerged out of seafaring, and their sailing prowess went back to the Romans, the Greeks, the Mycenaeans before them, and the Cretans and Phoenicians before that.

By the fourteenth century CE, the Genovese and the Venetians were competing for the Mediterranean trade in some of the biggest, sturdiest fleets around, and on the water, these Italians could fight. Venetians did vigorous business in Constantinople, and after the Ottomans took over they boldly opened commercial offices at Istanbul.

The Mediterranean trade drew tremendous wealth into Italy and spawned booming city-states, not just Venice and Genoa, but also Florence, Milan, and others. Here in Italy, money supplanted land as the chief marker of wealth and status. Merchants became the new power elite; families like the Medicis of Florence and the Sforzas of Milan supplanted the old military aristocracy of feudal landowners. All the money, all that entrepreneurial energy, all that urban diversity, all those sovereign entities in such close proximity competing for grandeur, eminence, and reputation generated a dy

namism unprecedented in history. Any talented artist or craftsman with a skill to sell could have a field day in the Italy of this era because he could get so many patrons bidding against one another for his services. Dukes and cardinals and even the pope competed to lure artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci to their courts because their works were not only beautiful but represented great status symbols. Italy began to overflow with the art, invention, creativity, and achievement that was later labeled “the Italian Renaissance.”

namism unprecedented in history. Any talented artist or craftsman with a skill to sell could have a field day in the Italy of this era because he could get so many patrons bidding against one another for his services. Dukes and cardinals and even the pope competed to lure artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci to their courts because their works were not only beautiful but represented great status symbols. Italy began to overflow with the art, invention, creativity, and achievement that was later labeled “the Italian Renaissance.”

Books, meanwhile, were coming back into fashion. During the Dark Ages, hardly anyone in Europe knew how to read except clerics, and clerics learned the skill just to read the Bible and conduct services. Among Germanic Christians, in Charlemagne’s time for example, clerics revered Latin, the language in which Christian services were performed, because they thought of it as the language God spoke. They worried that if their Latin deteriorated, God would not understand their prayers, so they preserved and studied a few ancient books written by pagans such as Cicero purely as an

aid to mastering the grammar and structure and pronunciation of the old tongue. They wanted to ensure that they would be able to continue sounding out syllables that would reach God. When reading writers such as Cicero, they tried assiduously to ignore what they were saying and focus only on their style so as not to be contaminated by their pagan sensibilities. Their efforts to preserve Latin petrified it into a dead language suitable only for ritual and incantatory purposes, in

capable of serving as a vehicle for discussion and thought.

3

Nonetheless, their reverence for books as artifacts meant that some churches and monasteries kept books tucked away in basements and back rooms.

aid to mastering the grammar and structure and pronunciation of the old tongue. They wanted to ensure that they would be able to continue sounding out syllables that would reach God. When reading writers such as Cicero, they tried assiduously to ignore what they were saying and focus only on their style so as not to be contaminated by their pagan sensibilities. Their efforts to preserve Latin petrified it into a dead language suitable only for ritual and incantatory purposes, in

capable of serving as a vehicle for discussion and thought.

3

Nonetheless, their reverence for books as artifacts meant that some churches and monasteries kept books tucked away in basements and back rooms.

Then, in the twelfth century, Christian scholars visiting Muslim Andalusia stumbled across Latin translations of Arabic translations of Greek texts by thinkers such as Aristotle and Plato. Most of these works were generated in Toledo, where a bustling translation industry had developed. From Toledo, the books filtered into western Europe proper, finding their way at last into church and monastery libraries.

The Arabic works found in Andalusia included a great deal of commentary by Muslim philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna to the Europeans) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). Their writings focused on reconciling Greek philosophy with Muslim revelations. Christians took no interest in that achievement, so they stripped away whatever Muslims had added to Aristotle and the others and set to work exploring how Greek philosophy could be reconciled with

Christian

revelations. Out of this struggle came the epic “scholastic” philosophies of thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and others.

The Muslim connection to the ancient Greek works was erased from European cultural memory.

Christian

revelations. Out of this struggle came the epic “scholastic” philosophies of thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and others.

The Muslim connection to the ancient Greek works was erased from European cultural memory.

European scholars began gravitating to monasteries that had libraries because the books were there. Then, would-be students began gravitating to monasteries with libraries because the scholars were there. While pursuing their studies, penniless scholars eked out a living teaching classes. Learning communities formed around the monasteries and these ripened into Europe’s first universities. One of the earliest emerged around Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Another very early learning community became the University of Naples. Then a university developed at Oxford, England. When

a fight broke out among the scholars there, the dissident group migrated to Cambridge in a huff and started a learning community of its own.

a fight broke out among the scholars there, the dissident group migrated to Cambridge in a huff and started a learning community of its own.

Other books

Just Shy of Harmony by Philip Gulley

Program 12 by Nicole Sobon

The Christmas Inn by Stella MacLean

The French War Bride by Robin Wells

Associates by S. W. Frank

Saint Francis by Nikos Kazantzakis

Black Moonlight by Amy Patricia Meade

Discovering Dalton (Manchester Menage Collection #2) by Nicole Colville

The Ajax Protocol-7 by Alex Lukeman

The Redeemed by M.R. Hall