Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (30 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

7.24Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Then it all came crashing down. On one of his forays east, Bayazid ran into a warrior tougher than himself—the dreaded Timur-i-lang. Bayazid’

s own feudal lieges had called Timur into Anatolia. They resented having lost sovereignty to the Ottomans, and so they sent a message to Timur, complaining that Bayazid was spending so much time in Europe, he was turning into a Christian. Well, Timur-i-lang would have none of that, for along with being a ruthless savage of unparalleled cruelty, Timur was also a Muslim who fancied himself a patron of the high arts, a scholar in his own right, and a devout defender of Islam.

s own feudal lieges had called Timur into Anatolia. They resented having lost sovereignty to the Ottomans, and so they sent a message to Timur, complaining that Bayazid was spending so much time in Europe, he was turning into a Christian. Well, Timur-i-lang would have none of that, for along with being a ruthless savage of unparalleled cruelty, Timur was also a Muslim who fancied himself a patron of the high arts, a scholar in his own right, and a devout defender of Islam.

In 1402, near the city of Ankara, these two civilized patrons of the arts set niceties aside and went at each other blade to axe, and may the worst man win. Timur-i-lang proved himself the more brutal of the two. He crushed the Ottoman army, took Emperor Bayazid himself prisoner, clapped him in a cage like some zoo animal, and hauled him back to his jewel-encrusted lair in Central Asia, the city of Samarqand. Despair and humiliation so overwhelmed Bayazid that he committed suicide. Out west, Bayazid’s sons began to war with each other over the truncated remains of his one-time empire.

It looked like the end of the Ottomans. It looked like they would end up having been just another of the many meteoric Turkish kingdoms that flashed and fizzled. But in fact, this kingdom was different. From Othman to Bayazid, the Ottomans had not just conquered; they had woven a new social order (which I will describe a few pages further on). For now, suffice to say that in the aftermath of Timur’s depredations, they had deep social resources to draw upon. Timur died within decades, his empire tattered quickly down to a small (but culturally brilliant) kingdom in western Afg

hanistan. The Ottoman Empire, by contrast, not only recovered, it began to rise.

hanistan. The Ottoman Empire, by contrast, not only recovered, it began to rise.

In 1452 it jumped to a higher level, a stage that began when a new emperor named Sultan Mehmet took the throne. Mehmet inherited an empire in good shape, but he brought one problem to the throne. He was only twenty-one and tougher, older men circled him hungrily, each one thinking that an older, tougher, hungrier man (like himself) might make a better sultan. Mehmet knew he had do something spectacular to back down potential rivals and cement his grip on power.

So he decided to conquer Constantinople.

Constantinople no longer represented a really important military prize. The Ottomans had already skirted it, pushing into east

ern Europe. Constantinople was more of a psychological prize: the city had immense symbolic significance for both east and west.

ern Europe. Constantinople was more of a psychological prize: the city had immense symbolic significance for both east and west.

To the west, an unbroken line ran from Constantinople back to the Rome of Augustus and Julius Caesar. To Christians, this was still the capital of the Roman Empire, which Constantine had infused with Christianity. It was only later historians who looked at this eastern phase of Roman history and called it by a new name. The Byzantines themselves called themselves Romans, and thought of their city as the new Rome.

As for Muslims, Prophet Mohammed himself had once said that the final victory of Islam would be at hand when Muslims took Constantinople. In the third century of Islam, the Arab philosopher al-Kindi had speculated that the Muslim who took Constantinople would renew Islam and go on to rule the world. Many scholars said the conqueror of Constantinople would be the Mahdi, “the Expected One,” the mystical figure whom many Muslims expected to see when history approached its endpoint. Mehmet therefore had good reason to believe that taking Constantinople would be a public relations coup that would ma

ke the whole world look at him differently.

ke the whole world look at him differently.

The many technical experts now working for the Ottomans included a Hungarian engineer named Urban, who specialized in building cannons, still a relatively new type of weapon. Sultan Mehmet asked Urban to build him something special along these lines. Urban set up a foundry about 150 miles from Constantinople and poured out artillery. His masterpiece was a cannon twenty-seven feet long and so big around that a man could crawl down inside it. The so-called Basilic could fire a twelve-hundred-pound granite stone a mile.

It took ninety oxen and about four hundred men to transport this monstrous gun to the battlefield. As it turned out, the Basilic was

too

big: it took more than three hours to load, and each time it fired it recoiled so hard it tended to kill more people behind it than in front of it. Besides, at a distance of a mile, it was so inaccurate it actually missed the whole city of Constantinople; but this didn’t matter. The big gun wasn’t an important military asset so much as an important symbolic asset—announcing to the world that

this

was the sort of weapon the Ottomans brought to the field. In a

ddition to the Basilic they had, of course, many smaller cannons. They were the best armed and most technologically advanced army of their time.

too

big: it took more than three hours to load, and each time it fired it recoiled so hard it tended to kill more people behind it than in front of it. Besides, at a distance of a mile, it was so inaccurate it actually missed the whole city of Constantinople; but this didn’t matter. The big gun wasn’t an important military asset so much as an important symbolic asset—announcing to the world that

this

was the sort of weapon the Ottomans brought to the field. In a

ddition to the Basilic they had, of course, many smaller cannons. They were the best armed and most technologically advanced army of their time.

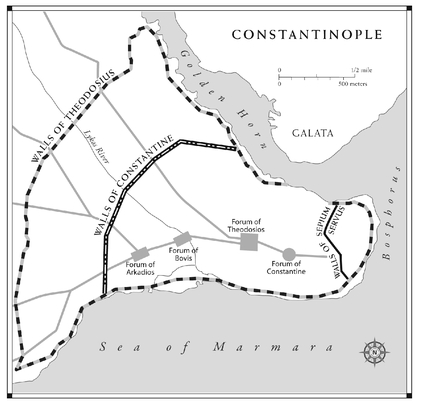

CONSTANTINOPLE: THE WORLD’S MOST IMPREGNABLE CITY

The siege of Constantinople lasted fifty-four days, the city being all but impregnable. Located on a triangular spit of land shaped like a rhinoceros horn, it faced the Bosporus Straits on one side and the Sea of Marmara on another. On these sides it had high sea walls and promontories commanding the narrow straits, from which the Byzantines could bombard any ships approaching the city. On the land side, it had a series of stone walls that stretched across the whole peninsula from sea to sea, each wall with its own moat. Each moat was broad

er and deeper and each wall thicker and taller than the one before. The innermost wall stood ninety feet high and was more than thirty feet thick; no one could get past that barrier, especially since the Byzantines had a secret weapon called Byzantine fire, a glutinous burning substance that was launched from catapults and splashed when it landed, sticking to flesh. It could not be doused with water—in fact, it was probably some primitive form of napalm.

er and deeper and each wall thicker and taller than the one before. The innermost wall stood ninety feet high and was more than thirty feet thick; no one could get past that barrier, especially since the Byzantines had a secret weapon called Byzantine fire, a glutinous burning substance that was launched from catapults and splashed when it landed, sticking to flesh. It could not be doused with water—in fact, it was probably some primitive form of napalm.

The Ottomans persisted, however. The cannons kept booming, the janissaries kept charging, the immense besieging army made up of recruits from many different tribes and populations including Arabs, Persians, and even European Christians kept storming the ramparts, but in the end, the battle turned on the fact that someone forgot to close one small door in one corner of the third and most impregnable wall. A few Turks forced their way in through there, secured the sector, opened a larger gate to their compatriots, and suddenly the most enduring capital of the western world’s lo

ngest lasting empire was going down in flames.

ngest lasting empire was going down in flames.

Mehmet gave his troops permission to loot Constantinople for three days but not one minute longer. He wanted his troops to preserve the city, not destroy it, because he meant to use it as his own capital. From this time on, the city came to be known informally as Istanbul (the formal name change would not occur until centuries later) and the victorious sultan was henceforth called Mehmet the Conqueror.

Imagine for a moment what might have happened if Muslims had taken Constantinople during the prime of Islam’s expansion, if Constantinople rather than Baghdad had been the capital of the Abbasids: straddling the waters linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, possessing all the ports they needed to launch navies across the Aegean and Mediterranean to Greece and Italy and on to Spain and the French Coast and through the Straits of Gibraltar up the Atlantic coast to England and Scandinavia, combined with their proven prowess in land warfare—all of Europe might well have been absorbed into

the Islamic empire.

the Islamic empire.

But seven hundred years had passed since the prime of the khalifate. Europe was no longer a wretched continent eking out a meager existence in squalid poverty. It was a continent on the rise. On the Iberian peninsula, Catholic monarchs were busy driving the last embattled Muslims back to Africa and funding sailors like Columbus to go explore the world. Belgium had developed into a banking capital, the Dutch were busy cooking up an awesome business expertise, the continent of Italy was muscling up into the Renaissance, and England and France were coalescing into nation-states. Const

antinople (Istanbul) gave the Ottomans a peerless base of operations, but Christian Europe was no longer any pushover. At the time, however, no one knew who was on the rise and who on the decline, and with the Ottoman triumph, Islam certainly looked resurgent to the Muslim world at large.

antinople (Istanbul) gave the Ottomans a peerless base of operations, but Christian Europe was no longer any pushover. At the time, however, no one knew who was on the rise and who on the decline, and with the Ottoman triumph, Islam certainly looked resurgent to the Muslim world at large.

Istanbul had only about seventy thousand people at the time of the conquest, so Mehmet the Conqueror launched a set of policies such as tax concessions and property giveaways to repopulate his new capital. Mehmet also reestablished the classical Islamic principles of conquest: non-Muslims were accorded religious freedom and left in possession of their land and property but had to pay the

jizya.

People of every religion and ethnicity came flowing in, making Istanbul a microcosm of an empire pulsing with diversity.

6

jizya.

People of every religion and ethnicity came flowing in, making Istanbul a microcosm of an empire pulsing with diversity.

6

Now the Ottomans ruled an empire that straddled Europe and Asia with substantial territory in both continents. The greatest city in the world was theirs. Their greatest achievement, however, wasn’t conquest. Somehow, in the course of their fifteen decades of rule, they had brought a unique new social order into being. Somehow, that anarchic soup of nomads, peasants, tribal warriors, mystics, knights, artisans, merchants, and miscellaneous others popula

ting Anatolia had coalesced into a society of clockwork complexity full of interlocking parts that balanced one another, each acting as a spur and check on the others. Nothing like it had been seen before, and nothing like it has been seen again. Only contemporary American society offers an adequate analogy to the complexity of Ottoman society—but only to the complexity. The devil is in the details, and our world differs from that of the Ottomans in just about every detail.

ting Anatolia had coalesced into a society of clockwork complexity full of interlocking parts that balanced one another, each acting as a spur and check on the others. Nothing like it had been seen before, and nothing like it has been seen again. Only contemporary American society offers an adequate analogy to the complexity of Ottoman society—but only to the complexity. The devil is in the details, and our world differs from that of the Ottomans in just about every detail.

Broadly speaking, the Ottoman world was divided horizontally between a ruling class that taxed, organized, issued orders, and fought, and a subject class that produced and paid taxes. But it was also organized vertically by Sufi orders and brotherhoods. So people separated by their classes might find themselves united in reverence to the same sheikh.

On the other hand, Ottoman society as a whole was compartmentalized into the major religious communities, each with its own vertical and horizontal divisions, and each a semi-autonomous nation or

millet,

in charge of its own religious rites, education, justice, charities, and social services.

millet,

in charge of its own religious rites, education, justice, charities, and social services.

The Jews, for example, were one millet, headed by the grand rabbi in Istanbul, a considerable community because Jews came flocking into the Ottoman world throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, fleeing from persecution in western Europe—England had expelled them during the Crusades, they had endured pogroms in eastern E

urope, they were facing the Spanish Inquisition in Iberia, and discrimination hounded them just about everywhere.

urope, they were facing the Spanish Inquisition in Iberia, and discrimination hounded them just about everywhere.

The Eastern Orthodox community was another millet, headed by the patriarch of Constantinople (as Christians still called it), and he had authority over all Slavic Christians in the empire, a number that kept increasing as the Ottomans extended their conquests in Europe.

Then there was the Armenian millet, another Christian community but separate from the Greeks because the Greek and Armenian churches considered one another’s doctrines heretical.

The leader of each millet represented his people at court and answered directly to the sultan. In a sense, the Muslims were just another of these millets, and they too had a top leader, the Sheikh al-Islam, or “Old Man of Islam,” a position created by Bayazid shortly before he was crushed by Timur-i-lang. The Sheikh al-Islam legislated according to the shari’a and presided over an army of muftis who interpreted the law, judges who applied the law, and mullahs who inducted youngsters into the religion, provided basic religious education, and administrated rites in local neighborhoods an

d villages.

d villages.

The shari’a, however, was not the only law in the land. There was also the sultan’s code, a parallel legal system that dealt with administrative matters, taxation, interaction between millets, and relationships among the various classes, especially the subject class and the ruling class.

Don’t try to follow this complexity: the complexity of the Ottoman system defies a quick description. I just want to give you a flavor of it. This whole parallel legal system, including the lawyers, bureaucrats, and judges who shaped and applied it, was under the authority of the grand vizier, who headed up the palace bureaucracy (another whole world in itself). This vizier was the empire’s second most powerful figure, after the sultan.

Or was he third? After all, the Sheikh al-Islam had the right to review every piece of secular legislation and veto it if he thought it conflicted with the shari’a, or send it back for modification.

On the other hand, the Sheikh al-Islam served at the pleasure of the sultan, and it was the sultan’s code the grand vizier was administering. So if the grand vizier and the Sheikh al-Islam came into conflict . . . guess who backed down. Or did he?

You see how it was: check, balance, check, balance. . . .

Other books

Center Field by Robert Lipsyte

Tristan (The Kendall Family #1) by Randi Everheart

License to Quill by Jacopo della Quercia

The Little Death by PJ Parrish

Almost an Angel by Katherine Greyle

The Triple Agent by Joby Warrick

All Grown Up by Janice Maynard

Her Heart's Captain by Elizabeth Mansfield

Storm and Stone by Joss Stirling

The Death of Nnanji by Dave Duncan