Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (526 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Turning to Mr. Jerome the Mayor said: “The town is proud of your literary and dramatic achievements, and of your unconquerable spirit, but, above all, it is proud of you as a man. Your pen has never been used unworthily, your humour has always been clean and refreshing, your serious work uplifting and your influence wielded for the betterment of mankind and the world.”

In his reply Mr. Jerome said: “Many of my literary friends are knights and baronets, others have received degrees of honour from the hands of Chancellors of Universities, and heads of Royal Societies. But I am the only literary man who has received his honour from the people. This Freedom of the Borough, it is the people’s knighthood. I take it you have conferred upon me the Knighthood of Walsall, and I shall always be proud of my spurs.”

Speaking of the town as represented to him by his father he said: “Behind your teeming streets and rearing factories I seem to see, like some faint ghost, that goodly town upon the hill, surrounded by its woods and heathland upon which the sun is shining.

“It may come again, the sunshine and the clean, bright streets, and the pleasant country round about. There is no reason why industrialism should not become civilized. There is no reason why factories should be ugly. There is no reason why men and women should live in sordid streets. Science holds out the hope that one day smoke and dirt will be banished from the land. Let us prepare for that time by keeping alive our love of beauty, by learning to value the finer things of life. You love music and art and poetry, I know. All wise men do. They are the food and drink of the soul. You have built yourselves noble buildings, you have made yourselves leafy roads and gardens. It was in a garden that man first talked with God. We banish God when we turn the country into slums. It is these things — religion, art, learning, music, literature — that are the important things. Business is very necessary. It is the bread of life. But a community does not thrive on business alone. It is by taking thought for the things of the spirit that a city shall prosper. Let us all work together for the prosperity of our good old town of Walsall.”

The Complimentary Dinner

Under the chairmanship of the Mayor, Councillor J. A. Leckie, there was a large and representative gathering at the complimentary dinner to Mr. Jerome in the evening. The ex-Mayor, Councillor Parry, proposed the health of the new Freeman. In the course of his remarks he said that when the resolution was before the Council the question was asked: “What would Stratford-on-Avon be without its Shakespeare? What would Lichfield be without Dr. Johnson? What would Stafford be without Isaac Walton? In the future men would ask, What would Walsall be without its Jerome K. Jerome? There is so much that is dull and drab in life that the humorist becomes a benefactor to the race. But it is when I turn to almost the last page of his last book that I find the real man. The humorist and the play-right become the prophet and the preacher. This is the man Walsall delights to honour. We hope he will carry away with him from Walsall pleasant memories of to-day.”

Mr. Jerome, replying, spoke under great emotion. He said: “Do you think you have gone the right way to get a speech out of me this evening?” He had made a few casual notes, he said, but he had hardly the heart to go on with them. After a while his humour gained the mastery, and he told an amusing incident concerning the production of

The Passing of the Third Floor Back

at Harrogate. The audience had expected something different from the author of “Three Men in a Boat”. He himself walked out of the theatre behind two old ladies. One, wiping her eyes, said: “Well, my dear, I did not think it was at all funny.”

“Never mind,” said the other, also wiping her eyes, “it does not do to be too critical. No doubt he was doing his best.” The next morning he read in the paper a criticism that “the play began all right, but towards the end the fun collapsed.” (Laughter.)

“Perhaps,” he continued, “it is as well that this very delightful day in my existence did not come too soon. It might have sent me down with a swelled head, perhaps; now it does not so much matter. I shall always remember this day, ladies and gentlemen, and it will be pleasant to think of one little place in England where one is thought about as a child of that town.”

Dr. Layton proposed the toast of “Literature and the Drama”. This was responded to by Mr. W. W. Jacobs, who kept the company in a state of continual merriment. He indulged in some delightful raillery at Mr. Jerome’s expense.

“The rewards of literature,” he said, “were very unequal. One man gets a tablet stuck on a house in which he says he was born, the freedom of a famous town is conferred upon him in a beautiful casket I should like to have stolen, and a public dinner given in his honour. Another man has to act as a sort of best man, carrying his train, so to speak, and whispering in his ear not to look quite so self-conscious and try to appear as though freedoms and public dinners in his honour were matters of every-day occurrence. (Laughter.) The rewards are unequal. As I say, one man writes about ‘Three Men in a Boat’ and lives in affluence; another man writes about boats of all sorts, and crews consisting of hundreds of people, and has to borrow money to pay his super-tax.

“I am very pleased to come to take part in this honour to Jerome K. Jerome, who is a clever man. I have always had a great respect for his intelligence since he took my stories thirty years ago, and asked for more. He is one of the best men I know. A lot of people say so, and he himself has never denied it. (Laughter.) He has never tried to. (Laughter.) I know a great deal in favour of him, but have never heard anything against him. Whether that is due to my carelessness or to his carefulness I will not say.”

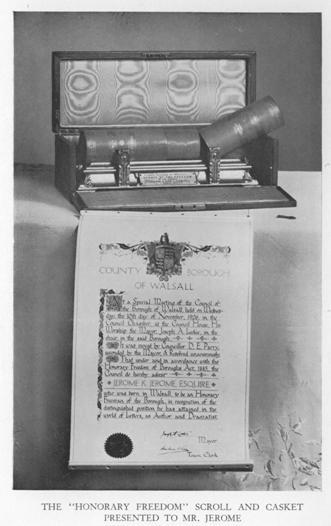

The Freedom Scroll

The Scroll conveying the Freedom of the Borough to Mr. Jerome is of the finest vellum inscribed by hand and tastefully illuminated in gold and colours. It is authenticated by the Borough Seal and signed by the Mayor and Town Clerk. Overleaf is a photograph showing the inscription.

During their stay in Walsall Mr., Mrs and Miss Jerome were entertained by Alderman and Mrs. Smith, J.P., is a Freeman of the County Borough of Walsall.

On returning to London after the “Freedom” ceremony Jerome expressed through

The Walsall Observer

his thanks to his fellow-citizens as follows:

Dear Walsall, Though I said all I could think of at the time, I feel I must write and thank you again for your wonderful hospitality and kindness to me when I was with you last week. You were there waiting for me in your streets — on your doorsteps, so to speak — with hands outstretched. There was more than welcome in your eyes. You gave me the feeling that behind your formal greetings there was genuine affection for me — that all these years you had remembered me, had been looking forward to my coming back.

It made me think of that dear Walsall nurse of mine that I mention in my memoirs who always thought of me as her boy.

I felt I was the guest of all of you. There were no class distinctions; your quiet, undemonstrative men; your placid, smiling women; your grave-faced little children who clamoured to be lifted up that they might wave their hands to me — you were, all of you, so evidently pleased to have me among you; you gave me the freedom of your hearts.

There were so many things I forgot to say when I was with you.

As a child in London I heard no music that I can remember; if I had remained with you I should have come to love it earlier. It must be that all children have music in them, and yours have been taught how to express it.

That children’s choir of yours that I heard in the Town Hall; it was wonderful! How I enjoyed it!

And the beautiful casket you gave me, of Walsall work, in which to keep the record of the honour you have done me — it will always be a joy for me to look at.

I shall always think of your music and your art. And, above all, of your sincerity and largeheartedness, and be proud of my relationship to you.

Yours affectionately,

JEROME K. JEROME.

Illness and Death

In May, 1927, Mr. Jerome, his wife and daughter visited Devonshire. They telephoned to Mrs. Kernahan Harris, at Ashburton, that they would call the next day. For a number of years Mrs. Jerome and Mrs. Kernahan Harris had been close and intimate friends; they were indeed as sisters to each other. After the message had been telephoned Jerome had a sudden but brief seizure. With medical assistance he recovered in a few hours.

The next day they decided to go to Ashburton as arranged. They could not go by car, as the doctor had told Jerome that he must not drive, so they went in the “Devon” ‘bus. Arriving at their friend’s house they had to climb a little hill to reach the plateau on which the house stands. Owing to his illness the day before he walked very slowly, but in a short time, after resting and breathing the clear fragrant air of the moorland, he became himself again.

When leaving, Mrs. Kernahan Harris accompanied them down to the gate opening on the road to wait for the “Devon” ‘bus to take them back. They all said “Good-bye”. But some presentiment must have been in Jerome’s mind, for as he was about to step in the ‘bus he looked back, and returning, took his friend’s hands again and said “Goodbye, Mary!” There was something in his face and voice so strangely impressive that, although Mrs. Kernahan Harris had not been told of the grim warning of the previous day, she afterwards wrote:

I knew, as I stood there, that I should never see my friend again. But the old, cheerful smile, the courage that made light of a physical weakness, was the last thing I saw — once more — before they were all lost to sight. And so, looking back — so smiling — I shall remember him.

On May 30th they all started by car on their homeward journey, Mr. Jerome declining his wife’s offer to drive and, contrary to medical advice, drove through Cheltenham to Northampton, where they put up at the Angel Hotel. He appeared in his usual health, but in the night he had another seizure which paralysed his right side. Miss Jerome immediately telephoned to London for the family doctor and it was found he was suffering from cerebral haemorrhage. The private nursing-homes being all full, he was removed to a private ward in the Northampton Hospital.

He never spoke after the seizure, but was conscious and able to recognize his dear ones and appreciate their loving ministrations until nearly the end. He passed peacefully away on June 14th at the age of sixty-eight.

It is pleasing to know that he suffered but very little after he was stricken down.

The funeral took place at Golders Green Crematorium on Friday, June 17th, the Rev. Herbert Trundle, Vicar of St. Alban’s, Golders Green, officiating. The principal mourners were Mrs. Jerome, Miss Jerome, Mr. Harry Shorland, Mr. Frank Shorland and Mr. Frank Bannister (nephews) and Mrs. Harry Shorland. Among those present were Councillor J. A. Leckie (Mayor of Walsall), Mr. George Wingrave, Mr. Carl Hentschel, Dr. Woodley Stocker, Mr. W. Walsh, Mr. G. B. Burgin, Mr. Will Owen, and Mr. P. H. King.

At the time of the funeral a memorial service was held at Walsall in the church which Jerome’s father, in his prosperous days, was instrumental in building.

In the course of his address the Rev. J. W. James said: “Jerome K. Jerome spent his life in climbing Mount Parnassus; most of us live on the plains of life. The ideal life seems remote, and at times, sick at heart, we turn to the books and painting and music of men who have struggled upwards, and live the glorious life of the spirit on the mountains whose very slopes are often hidden from our view. In the future days many of us will turn in an hour of weariness and sickness towards Mount Parnassus, and in our delight we shall find that the voice of Jerome K. Jerome can still come with power to gladden and inspire. ‘He being dead yet speaketh’.”

His last resting-place is the beautiful churchyard at Ewelm, Oxfordshire.

One autumn day in 1928 three friends, Mr. Frank Shorland, Mr. George Wingrave and the present writer, visited the historic church at Ewelm. In the chancel of this church Chaucer’s son lies buried. Jerome K. Jerome and his family worshipped there when they lived at Wallingford, and now in its picturesque churchyard his ashes sleep in silence. The three friends each placed flowers upon his grave, which is side by side with that of his sister Blandina and his stepdaughter.

Archbishop Trenche’s lines came to mind as a fitting and almost literal description of the scene:

“And formed from out that very mould

In which the dead did lie

The daisy, with the eye of gold,

Looked up into the sky.

The rook was wheeling overhead,

Nor hastened to be gone;

The small bird did its glad notes shed,

Perched on a grey headstone.”

The text of Scripture on his gravestone is “For we are labourers together with God” — I Cor iii, 9.

This was a striking reminder of his self-imposed mission — to take happiness into the homes of the poor and help to bring back to God His unhappy world.