Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (524 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Here Sir Charles Higham struck a deep note; the first necessity for man is to be human. Jerome knew the soul of the people, having spent his sad childhood and youth among them. He knew their hardships and sorrows, and was ever-ready to lend a helping hand to those in misfortune. A letter to Coulson Kernahan gives one example of this:

My dear Jack, May I ask your help for a wife and family (left utterly destitute) of a young brother writer? Poor fellow died last week after a long illness, which took all his resources and left his young wife and two babies to battle with the world by themselves. He was only a youngster (twenty-five), Herbert Adams — not a genius, but a humble, ready worker, journalist, essay-writer, poet, etc., etc. I shall do what I can among the societies, but their wants are pressing. I know your weak points, and take, I fear, a mean advantage....

Yours ever, JEROME.

Besides being in sympathy with his fellow men, Jerome believed that there is a kinship running through

all

living creatures. Indeed, his love for birds and dumb animals was part of his religion. During a hot, dry summer, he had coco-nut shells filled with water and placed on the trees in the woods around his house so that the birds could drink.

“On one occasion,” his secretary writes, “while writing to his dictation I was surprised to hear him break off in the middle of a sentence and say:

‘Well, what do you want?’ On looking round I saw a sparrow had entered the study and was hopping round his feet and not making the slightest attempt to fly away. It was typical of the man that he did not move until the little visitor hopped out of its own accord into the garden.

“He was merciless in his anger towards any person whom he found ill-treating a bird or animal.”

When the Great War was drawing to its close and peace celebrations were being talked about, a bird-lover suggested in the Press that one way of celebrating peace would be to liberate all caged birds. The following is an extract from a letter that Jerome wrote to the paper upon the suggestion:

From what I know of them, I do not believe we could give our boys at the Front any greater pleasure than this little gift of mercy to the sweet singers of our lanes and fields.

We hear how this war is to lift up and purify the nations. How we are to emerge from it braver, truer, kinder. God grant it may be so. Meanwhile, might we not begin with this little thing that to many of us means so much? We are fighting for liberty. Cannot our hearts be big enough that even our little fellow artists, the birds, shall have their liberty and share in our triumph?

JEROME K. JEROME.

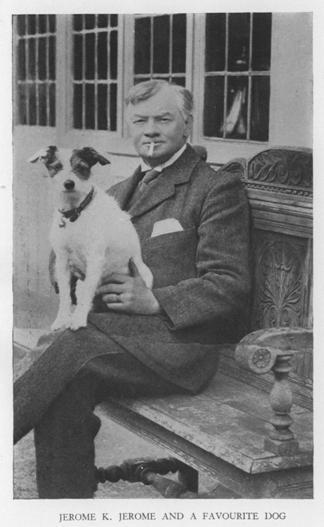

Jerome’s lady secretary also writes about his favourite dog, “Max”:

I shall always in my memory of him associate J. K. J. with Max. He was sitting in his study-chair at “Monks’ Corner” when I first saw him with his magnificent Great Dane lying at his feet. They made an imposing picture. The white-haired gentleman, with his quaintly humorous smile, and his grave-eyed canine companion seemed to my mind complemental to each other.

When we were at work Max would stroll quietly in, stand for a few moments looking round, and, when he found his master was busy, would come to each desk, give us a wet, doggy greeting with his tongue, and just as quietly amble out. He was a splendid creature, and it was a great grief to his master when he contracted cancer of the throat and had to be destroyed.

In Mr. Jerome’s garden was a pool of water into which frogs would sometimes jump, and if they were not taken out they would drown. Jerome made with his own hands some little steps to enable them to climb out.

To him there was a mysterious relationship between all living things, uniting them into one family, and there was an indefinable pleasure in rendering any little act of kindness to the humblest of living creatures.

Jerome’s Religion

Behind all his humour, the key to his character lay in his religion. He had a profound belief in the value of all sincere religious faith. To millions of people religion is the most important thing in life. He realized as Goethe did, that beyond the grandeur and elevation of Christianity the human mind need not advance.

To him religion was a very beautiful thing, broad-based upon the ineradicable principles of humanity, brotherhood and charity. It meant all men working together for the common good; “playing the game”, whether in sport, business, or politics — indeed in every walk of life. He believed that foundations of religion must be based upon truth, because the appeal of truth finds a point of contact in men and women generally. He was also convinced of the utter hopelessness and despair that comes with no faith.

It was characteristic of him that he could always see both sides of a religious question, but he once remarked to the present writer that he could not swallow everything that divines asked him to; saying in his humorous way that “he had not the stomach of an ostrich, and was unable to digest nails”.

Like most serious-minded people, Jerome wished to be orthodox, but he could only be orthodox by believing the dictates of his own conscience.

“In five hundred years from now,” he remarked, “the accepted dogmas of to-day will have changed, perhaps beyond recognition, but the voice of conscience, and the need of communion with the Unseen, will be then just as now.”

To him the unhappy divisions into which Christianity is rent was painful. He said the man in the street was bewildered and knew not which voice to believe. Christianity, as represented by its accredited teachers, had become a confusion of tongues, a never-ending disputation between pulpit and pulpit. The practice of elevating non-essentials into first principles had engendered much strife and bitterness. In theory Christian people love one another, in practice they often do exactly the opposite; the consequence is that the masses have little to guide them but their own consciences.

At the same time he believed that in the religious world men were groping after truth and reality. All that is wanted to produce order out of chaos is a great and inspired leader. When such a man arrives he will find that there burns in the heart of English people unmistakably and unshakably a deep and passionate religious conviction.

On December 16th, 1893, J

erome

wrote in

To-day

a remarkable article which at the time caused much discussion, entitled “Is Christianity Played Out?”

“I ask the question,” he said, “in no irreverent spirit; Christianity, although indirectly responsible for many dark pages in the world’s history, has been the most ennobling influence given to humanity, and I most earnestly desire to be classed amongst those who acknowledge the grandeur of its teaching and who pay reverence to its mighty founder.

“But a religion that has outgrown its strength to be up and doing, that sits inert, a voiceless mummy, bedizened with the trappings of mere word-worship, is a thing best buried and forgotten. In all seriousness I ask if Christianity has come to this pass amongst us. Is it a live force in our midst this day, or but a painted figure-head upon the ship of State? Have we become a Christian people, carrying out our Christianity by proxy, instead of being a people of Christians?

“The other week I briefly alluded to the case of a woman who died of starvation in Kensington, W. The woman’s sister, who was living with her — or, rather, dying with her — begged her to consent that they should go into ‘the house’, but the woman, who had earned her own bread for over half a century, shrank from the public shame. ‘The Lord will provide for us,’ she answered — and died. We read the report in the morning paper and pass it by with a sigh.

“But shift your vision for a moment. Be that other starving woman watching the only thing you have to love on earth slowly dying before your eyes. Think of the daily, hourly prayer for help; for a little bread, for a little coal; and the feeble voice grows feebler and feebler, drowned by the voices of the cheerful street and the joyous clanging of the church-bells of the Christians — until it ceases.

“Take another example. An old woman of seventy drowns herself in the Serpentine. ‘I have no home and no food,’ she writes, leaving the letter behind her for the living, ‘and so I have made up my mind to end it. I can’t get work because I am deaf and old. My hope is gone. May the Almighty forgive me!’ So the old soul, having finished her letter, totters through the long streets where dwell so many Christians to her comfort; and the muddy waters, closing over her, shut out from her ears the kindly voices urging on the hungry to have faith....

“Towards the end of the same week an old soldier, a man who had been through Alma, Inkerman, Balaclava and Sebastopol, died of want at Bromley. He, also, preferred death to ‘the house’.

“A Christian government, we say, provides ‘the house’. We subscribe to this charity, that society, the other organization. Let the officials look after our brothers.

“It can’t be done, my friends; we can’t do our duty in this world by deputy. This automatic machine of ours, into which we put our gold at one end and our brother draws his dole at the other, is clogged and will not work.... It is

you

he wants. Give him your help and sympathy as from human being to human being and he will thank you for it. Christ and His disciples did not go about collecting money for the poor; when their day’s work was done they went into the houses of the poor. Their friends were poor. It is human hands, human hearts that are wanted. God’s work can never be done by societies. It is done by men and women. If each man took his work in his own hands the world would be more what God meant it to be.”

Jerome certainly took his work into his own hands. He was the last man to advocate anything he could not live up to himself. His was a practical Christianity; but he carried out his acts of kindness so unobtrusively that the world knew little or nothing about them.

His religion was not of the seraphic kind that lives too much in the clouds to be any use in this plain, prosaic world of ours. Religion to him was a tremendous reality — something he could apply to his daily actions and to the common life to render it useful.

When living at Wallingford and Marlow Jerome took but little interest in the town’s affairs. He preferred devoting the time at his disposal to work in which he was profoundly happy, namely, with his devoted wife ministering to the wants of the poor. Theirs was not the generosity that headed subscription lists, as far as possible it was anonymous. The friend in trouble, the man “down on his luck”, the woman oppressed by family anxieties, the bread-winner lying ill — these loomed largest in his thoughts and were the duties that each day brought, that must in the natural order of things “come first”. These duties were performed with great-hearted human sympathy.

A friend with small means and but little time at her disposal had reason for anxiety about her young sister on the Continent. Jerome put down his work, closed the door of the room in which he worked, and, with his wife, put a few things together and started for the Continent that night. A guest was staying in the house, but their hurried departure was understood. Nobody else could go, and whatever the inconvenience, they must.

A charwoman at “Monk’s Corner” had a delicate child; without the slightest display the little one was sent for a change into the country.

A man was out of work. Jerome, anxious to interview an employer, called at his London office seven times in one day. This incident has been spoken of as a myth; but those who knew him best say it has an amazing resemblance to fact.

These are a few instances out of many that can never be recorded, which show how Jerome played his part on the stage of life, a part which he faithfully continued to play until the curtain dropped.

In view of the fact that Jerome wrote an autobiography, the question may be asked, “What need is there for another story of his life?” One answer to that question is that Jerome was not the man to place on record his own countless good deeds and acts of kindness to the poor. These were known only to those who were nearest to him. But it is right that they should be widely known. As Shakespeare finely says:

“One good deed, dying tongueless, Slaughters a thousand, waiting upon that.”

Jerome helped the poor without a thought that he was even doing right, and thereby gaining some credit to himself. He helped the poor because it made

them

happy. His own happiness was, no doubt, incidentally heightened, because good deeds such as Jerome delighted in can never be thrown away. They imperceptibly but unmistakably help to fashion a better and kindlier world.

Jerome’s Politics.

In his speech after being presented with the Freedom of the Borough of Walsall, Jerome said:

“Now that I am one of you, and that you may know all about me, and that nothing may be hid, I ought perhaps to confess to you my politics — not an unimportant matter in a fellow-citizen. I am happy to say that I have been at various times in complete agreement with the political opinions of every one of you. (Laughter.)