Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (523 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

He himself wrote in “They and I”:

Life is giving, not getting.... It is the work that is the joy, not the wages; the game, not the score. Life is doing, not having. It is to gain the peak the climber strives, not to possess.

With Jerome, every defeat was a step towards further victory. He may be likened to a famous Italian general, who, being asked in his old age why he was always victorious, replied that it was because he had been so often defeated in his youth.

Jerome’s Travels

It would be difficult to write about J. K. J. taking a journey without noting his propensity for packing. He prided himself upon his skill in packing hampers and trunks. It was almost an infatuation with him. At one period of his life, if he did not do the packing, he would not take the journey. His genius for packing, no doubt, led to that delightful humour in “Three Men on the Bummel”, called “The Wisdom of Uncle Podger”:

“Always before beginning to pack,” my uncle would say, “make a list.”

He was a methodical man.

“Take a piece of paper” — he always began at the beginning—” put down on it everything you can possibly require; then go over it and see that it contains nothing you can possibly do without. Imagine yourself in bed; what have you got on? Very well, put it down — together with a change. You get up; what do you do? Wash yourself; what do you wash yourself with? Soap; put down soap. Go on till you have finished. Then take your clothes. Begin at your feet; what do you wear on your feet? Boots, shoes, socks; put them down. Work up until you get to your head. What else do you want besides clothes? A little brandy; put it down. A corkscrew; put it down. Put down everything, then you don’t forget anything.”

That is the plan he always pursued himself. The list made, he would go over it carefully, as he always advised, to see that he had forgotten nothing. Then he would go over it again and strike out everything it was possible to dispense with. Then he would lose the list.

There is also a very amusing account in “On the Stage and Off” of a huge hamper which he says he bought when he first went on the road as a travelling player. This hamper let him in for a good deal of chaff from railway porters, and sarcasm from landladies. He tried to lose the thing, but no matter where he left it it always followed him.

When Jerome and George Wingrave lodged together they went occasionally to Belgium and France, Jerome always doing the packing. A few years later, after his marriage, Jerome discovered that his books were more widely read and appreciated in Germany than in England. “Three Men in a Boat” was read throughout the country, and “Three Men on the Bummel” had been adopted as a school reading-book. His plays were running in many German Theatres. Naturally, he decided to go. On arriving at Freiburg he took lessons in the German language from Professor Dr. Gutheim, with whom he formed an intimate and lifelong friendship.

Since Jerome’s death, Dr. Gutheim has broadcast a number of wireless talks in Germany about Jerome. He has also written a number of articles in literary journals, cuttings of which the Professor has kindly sent for use in this book. The following brief extract is a translation from the German:

The man of whom I am about to speak is, perhaps, next to G. B. Shaw and Oscar Wilde, the one among modem English literary stars who is best known beyond the bounds of his own country; whose works have been translated into all languages and read everywhere with pleasure.

It is the English writer, Jerome K. Jerome, whose humorous story, “Three Men in a Boat”, has been spread abroad to a degree seldom experienced.

I myself had the pleasure of knowing him when he made a long stay in Freiburg during his journey through Germany, when I was with him during his stay.

I am still, after long years, grateful for the stimulating hours which I spent in his company and for the clever and dry-humoured conversations which I enjoyed with him.

Professor Gutheim sketches, with much accuracy, Jerome’s career from the time of his birth in Walsall, all through his struggles and successes until his death in 1927. He speaks of him in the highest terms as a friend, and of his writings with enthusiastic appreciation.

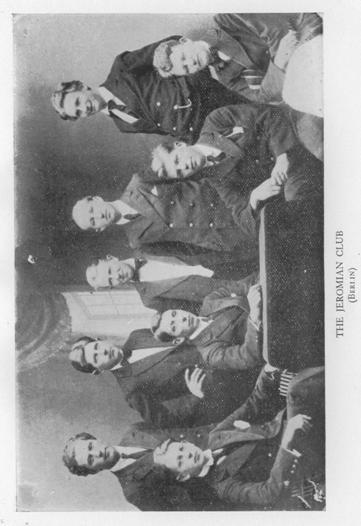

While Jerome was in Berlin a number of young men formed themselves into a club with the object of reading and studying his writings. It was called “The Jeromian Club”, and meetings were held regularly.

“In Dresden,” said Mr. Jerome, “there was quite a large English colony. We had a club, and a church of our own, with a debt and organ fund just like the churches at home.”

He then went to Russia, and found that at St. Petersburg he was already famous. A number of bearded Russians, so he himself said, met him at the station and insisted upon kissing him.

He made the acquaintance of a Russian General and his wife. The latter could speak English and had helped to make Jerome’s name known in Russia. She also acted as his interpreter.

Mr. Maurice Baring, in his book “Puppet Show of Memory”, mentions meeting with a Japanese Military Attache and a Russian student in St. Petersburg. The conversation turned on English literature. The Russian student said his two favourite modern English authors were Jerome K. Jerome and Oscar Wilde. When Baring showed some surprise at his choice, the student said: “You seem to think I refer to Jerome as a comic writer. You probably have not read ‘Paul Kelver’, which is a masterpiece and a real human book — a great book.” Baring also states that Jerome’s books were to be seen on the bookstalls and newspaper kiosks in Central Russia.

In his book “American Wives and Others”, Jerome relates an amusing account of his return journey from Russia to Germany:

A friend gave me a little dog to bring away with me. It was a valuable animal and I wished to keep it with me. It is strictly forbidden to take dogs into railway-carriages. The list of pains and penalties for doing so frightened me considerably. “Oh, that will be all right,” my friend assured me. “Have a few roubles loose in your pocket.” I tipped the station-master and I tipped the guard, and started, pleased with myself. But I had not anticipated what was in store for me. The news that an Englishman with a dog in a basket and roubles in his pocket was coming must have been telegraphed all down the line. At almost every stopping-place some enormous official, generally wearing a sword and a helmet, boarded the train. At first these fellows terrified me. I took them for Field-Marshals at least. When they saw the dog their astonishment was boundless. Visions of Siberia crossed my mind. Anxious and trembling, I gave the first one a gold piece. He shook me warmly by the hand. I thought he was going to kiss me. If I had offered him my cheek I am sure he would have done so. With the next one I felt less apprehensive. For a couple of roubles he blessed me — so I gathered — and, commending me to the care of the “Almighty”, departed. Before I reached the German frontier I was giving away the equivalent of English sixpences to men with the bearing and carriage of Major-Generals; and to see their faces brighten up, and to receive their heart-felt benedictions, was well worth the money.

Jerome visited Switzerland and called upon Hall

Caine, who happened to be there, and was in the middle of writing “The Christian”. It was snowing, but Jerome suggested a walk. Hall Caine agreed and said he knew a short way to Pontresina. They had not gone far when they were up to their waists in a snowdrift. Hall Caine said: “I know where we are now, we are in a hollow, we ought to have turned to the right.” They at once turned to the right, and in a short time were up to their necks. Jerome said he had been to Pontresina and didn’t think much of it. “Perhaps you’re right,” said Hall Caine, as they retraced their steps.

Jerome made three tours through the United States and lectured or gave readings in every State. President Roosevelt expressed a wish to see him. Jerome and his wife called; curiously enough Roosevelt had that morning received a letter from his son mentioning Jerome’s books. They had an interesting talk, and Jerome was much struck with the President’s boyishness. A few years later Jerome spoke his mind freely and frankly about the injustices and wrongs the negro races in America suffer at the hands of white men. Nevertheless, after finding out all he could about his fellow-beings in that country, he expressed the opinion that the American, taking him class for class and individual for individual, is no worse than the rest of us.

Service in the War

Jerome’s lady secretary writes:

I can remember as if it were yesterday how grieved and sorrowful he was on that fateful August morning. He knew Germany well, and realized what so many did not, that it would be a long and bitter struggle. There were some who thought that because he did not believe all the tales of atrocities served out by the Press that he was a pro-German. It was utterly untrue. There was no more loyal Englishman, but his heart was torn at the thought of the frightful sacrifice of young lives. He did not presume to pronounce judgement on the authorship of the world-struggle. His thoughts were always for the lads who were day by day sacrificing their lives. When the ghastly news came of the sinking of the

Lusitania

he was unable to work. A very dear friend, Mr. Charles Frohman, had perished.

On the suggestion of a member of the British Cabinet he went to America to assist in English propaganda. He made speeches in many large centres and had an interview with President Wilson, who conveyed the idea that America was preparing herself to come in at the end as peacemaker. At a dinner in Washington an important group of German bankers and business men assured Jerome that Germany had already realized that she “had bitten off more than she could chew”, and would welcome a peace conference. He brought back the message to England, but the idea of a conference came to nothing.

He then offered himself for active service but was rejected by the British Army Authorities as being over age. He was, however, accepted by the French Red Cross Society as an ambulance driver.

“One bitter night,” writes his secretary, “I struggled through the deep snow to receive his final orders. I can see him now, straight and virile in his blue uniform. I believe he was fifty-seven at the time, but that night he did not look more than forty.”

He was “Ambulance Driver Nine”. He went through all the hardships that every Tommy who came back from France talks about, with rain almost unceasing and mud everywhere. From rain the weather would change to frost, when the thermometer would register several degrees below zero. He would spend nights beside a mud-locked car, listening to groans and whispered prayers. Cars would be overturned, their load of dying men would “mingle in a ghastly heap of writhing limbs” from which the bandages had come undone.

To one so sensitive and tender this was heart-rending. The sorrow of it never entirely left him. He was in France about a year.

“When he came home,” his secretary writes, “the old Jerome was gone. In his place was a stranger.

He was a broken man.”

Some time afterwards his medical adviser, Dr. T. Wingrave (George’s brother) warned him that his heart was affected.

He joined a small but influential group of men who believed the time had come to end war by negotiation. The group included Dean Inge, Lord Buckmaster, the Earl of Beauchamp, Lord Lansdown, and John Drinkwater. Meetings were held, and their action, no doubt, satisfied their consciences, but it was generally regarded as premature.

The War did not have a very great influence upon him as an artist. The characteristic features of his writings were much the same after the War as before. If there was any change at all, his seriousness was deepened and his work had just a tinge of sadness.

“A Human Man.”

In 1926 Jerome was entertained by the members of the O.P. Club at the Hotel Cecil, London. Sir Charles Higham, president of the Club, in the course of his speech, asked:

“How is it that the man who could write ‘Three Men in a Boat’ could also write ‘The Passing of the Third Floor Back’? One full of humour, while the other touched the tenderest chords in their composition. I think I know the explanation. It is because he is such a human man. You can’t write such things unless you know the soul of the people.”