Delphi (44 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

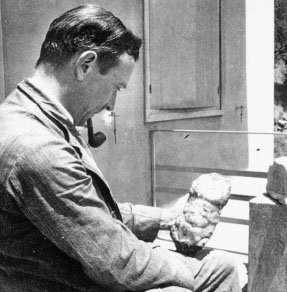

Figure 13.3

. Pierre de la Coste-Messelière, smoking his pipe, examining sculpture from the tholos in the sanctuary of Athena at Delphi (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 124])

The scale of operations at Delphi increased dramatically in 1935, through design and necessity. During the year, plans were made to plant 6,500 pine trees around the site to make it more picturesque, although eyebrows were raised at introducing non-native vegetation to the area (see

fig. 0.2

). A new cycle of excavations had also just begun under an incoming generation of scholars who would become central figures in Delphic folklore: Pierre Amandry, Jean Bousquet, Jean Marcadé, Lucien Lerat, and Jean Pouilloux. But then, in December 1935, tragedy struck. A massive storm caused a rock-and mudslide that covered large sections of the site. In one stroke of nature's power, the big dig was partially wiped out. Delphi was, once again, hidden from view.

18

The authorities were quick to act. In 1936 the French government made new resources available to dig Delphi out again. Back came the

wagons from the original excavation; the train tracksâstill visible today in places at Delphiâwere oiled into operation, the wooden slides were reconstructed to help ferry material down toward the wagons, and work began. But this time the excavators dug deeper than the original ones had, focusing this time on uncovering Delphi's earliest history, whereas the earlier one had sought to uncover what Pausanias had seen in the second century

AD

. It was during these campaigns that Delphi began to give up more of its most closely guarded secrets: buried caches of ancient sculpture (including some from the early temple) and particularly the rare ivory and bronze sculptures that are now on display in the site's museum (see

plate 5

,

fig. 4.2

).

19

The late 1930s were a busy time at Delphi. A new road from Arachova was built to the site in 1935, the road from Itea was improved, and excavations at the ancient port site were undertaken between 1936 and 1938. A new museum to house the expanding collection of finds opened in 1938. The French constructed a new dig house to cope with the larger number of people working on a regular basis, and it was inaugurated in April 1937 and promptly put to good use when a snowstorm kept everyone inside for five days. Work continued also on reconstructing other parts of the sanctuaries. Several of the columns of the round tholos structure in the Athena sanctuary were reconstructed, creating one of the most iconic (and yet, ironically, least understood) images of ancient Greece in the modern tourist literature (see

plate 3

). In 1938 work began on rebuilding several columns of the Apollo temple,

20

though not all offers of help were accepted. For instance, in the 1930s a rich American woman offered to pay for the rebuilding of the Naxian Sphinx upon its high column and was refused in large part because the lady wished to see a large elephant carved onto the Sphinx's supporting column, apparently the symbol of her favorite political party.

21

World War II did not halt work at Delphi as completely as had World War I. Following the French armistice, some scholars were able to return, and even while Greece was involved in the fighting, work could still, just about, continue. The looming war clouds in 1938â39 meant

that work on reconstructing the temple was postponed, and that the focus was changed to protecting the site and its contents. Some finds were dispatched for safe-keeping in Athens, but many were simply buried in the Delphi landscape. An excavated Roman underground tomb was put to use as a safety vault and hidden from public view. Massive holes were dug into the ground on the hillside, into which sculptures were lovingly placed covered in sheets and wrapping to protect them from the earth (

fig. 13.4

). A careful ledger was made of the exact position and contents of each underground deposit, so that, like squirrels with their food, the scholars could find them again when the time was right. The sad truth was that most were not exhumed again till long after the Greek civil war in 1952 (

fig. 13.5

). Delphi's treasures were once again consigned underground, this time for over a decade.

22

Figure 13.4

. Delphic statues are hidden underground in preparation for World War II (

BCH

1944â45, vol. 68â69, pp. 1â4 fig. 5)

Figure 13.5

. The excavators rejoice as Delphic sculptures are finally returned to the light in the early 1950s (© EFA/J. Bousquet [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 150])

During the war, hunger was the biggest problem for the local population and archaeologists. Parts of the site were given over to agricultural cultivation of foodstuffs, and chickens were kept around the French dig house. Inflation was rampant (in 1944 the government had issued a note for 100,000,000,000 drachma), and money, as a result, was pretty much disbanded as a viable system of exchange. Yet many scholars made Herculean efforts to return each season, taking trains, vans, bicycles, donkeys, and even walking on foot to reach their goal. To some, surely, returning to Delphi offered a sense of continuity in a world turned upside down, and without doubt a chance to escape the depressing reality of world events. But sometimes those events came to Delphi. In 1942 the Italian Black

Shirts camped nearby, used the Castalian spring as their water source, and the stadium as an arena for target practice. The French scholar Pierre Amandry, often resident at Delphi during the war, later scoffed that their aim must have been very poor, as not many of the ancient stones were harmed (

fig. 13.6

). On Easter 1943, the role of ancient Delphi as a reunion place of nations was reenacted when British forces met with Greek partisans to plan their resistance. A month later, however, the Italians were back, this time conducting “archaeology” while looking for weapons caches the British may have left behind.

23

But Delphi's closest encounter with the brutal face of war, an experience with which it was not unfamiliar given the four Sacred Wars fought over itânot to mention its having been the focus of Persian and Gaulish

invasions in the ancient worldâoccurred in September 1943. Following the Italian surrender, German forces moved in to take control and were immediately attacked by Greek partisan forces hiding among the rocks in the area of Delphi. The German response was immediate, with a full battle taking place in and around the Delphic gymnasium and sanctuary of Athena. Pierre Amandry, resident at Delphi at the time, recounts that one hundred bodies were left among the olive groves surrounding the site as a result of the fighting (see

fig. 0.2

). That night he and the Greek site overseers, along with the local villagers, evacuated the site and withdrew up into the mountains, as centuries earlier, in 480

BC

, ancient Delphians had done when the Persians attacked Delphi. In the mountains, they met with the partisan fighters, many of whom had been workmen on the excavation site before the war. The Greeks continued to resist German advances at the narrow pass of Delphi for two days, until the Germans retreated. Amandry and the locals came back down from the mountains, and, despite some ongoing shelling from German gunboats down by the port and several aerial bombardments, the Greek flag was raised at the ancient sanctuary and the church bells rung. Delphi had once again defeated its invaders.

24

Yet even Delphi could not withstand a ferocious renewed invasion the following year in the final phases of the war. Nor could it be unaffected by the bitter civil war that occupied Greece in 1947â49, which made travel to the site even more difficult since, once outside the zones patrolled by the government, travelers were at the mercy of the fighters asking first and shooting later or vice versa.

25

Figure 13.6

. Pierre Amandry (with pipe in mouth), while excavating at Delphi, joins a group of Greek resistance fighters for a photo (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 147])

On 10 July 1952, the many statues that had been hidden out of sight at the outset of the World War II were dug up and put back on display (see

fig. 13.5

). Following a decade of on-off conflict, there was much work to be done to put the site back in order, including everything from clearing the agricultural crops planted during the war and the general overgrown vegetation, to the recollating of site information following the theft and destruction of much of its archives, and the organization of the physical remains of the site to make it manageable and accessible once again to tourism.

But still Delphi retained a wonderful air of nonchalance. There were no barriers round the site, no tourist fee to enter: Delphi was still intrinsically

part of the local community. Villagers on donkeys would use part of the sacred way to crisscross the mountainside; and at night the local lads would use the theater as a place to hang out, drink, sing and dance, including, according to one scholar's memoirs, “George the local hairdresser with his guitar,” who could be found there on many occasions.

26

All this changed in 1956 when electricity finally arrived at the museum, the road leading to the site was widened, and the site itself was enclosed, its access regulated. Tourism numbers began to increase substantially over the coming decades. Between Cyriac of Ancona in 1436 and the first excavations in 1892, just over two hundred people are recorded as having come to Delphi.

27

In July 1936 alone, there were 165. In July 1990, there were 77,900.

28

Delphi now welcomes over two million visitors a year. It is not surprising how much of the work at the site itself has been focused on preparing and maintaining it for such an onslaught, most recently, in 2004, with a new museum opening to chime in with the Olympic Games in Athens (see

figs 0.1

,

0.2

).

29

It is a job never complete. Concern continues over how to protect the site from its increasing use; how to protect the tourists from the continuing rockfalls (the Kerna fountain was destroyed by a rockfall in 1980 and the stadium was closed to visitors in 2010 because of a serious rockfall in that area); and how to protect the area from the damage caused by the vibrations from the large number of buses each day that travel the road just outside the sanctuary and the damage caused by their petrol emissions to the ancient stones (a problem compounded by the acid produced by the local conifer trees).

30