Delphi (43 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

Figure 13.1

. A photo of the excavation in full progress, with the train tracks and wagons in use as the entrance to the Apollo sanctuary is cleared (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 77])

And the task of excavation was enormous. Homolle was assisted by a small team of archaeologists; by the most competent of work managers, Henri Convert; and by over two hundred workmen. Eighteen hundred meters of train track were laid crisscrossing the site on which fifty-seven wagons took the earth away as it was excavated (

fig. 13.1

). The tracks were laid at such a gradient that, when full of earth, a single workmen could use gravity to push them easily by hand away from the excavation toward the dumping area, and then packs of mules were used to pull them empty back up to the excavation area. In 1895 alone, 160,000 wagonloads of earth were excavated (see

fig. 13.2

).

3

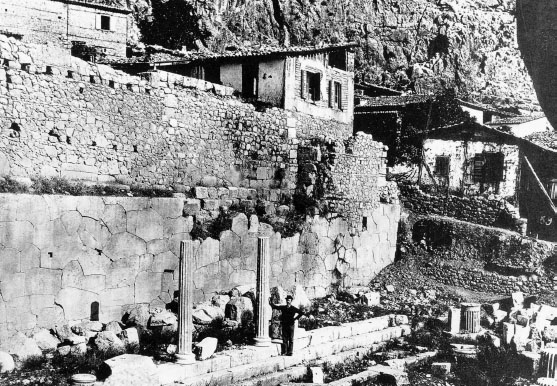

Figure 13.2

. An early photo of the excavation in progress with the Athenian stoa and temple terracing wall emerging from underneath the modern village of Castri (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 66])

The initial finds were impressive, even compared to some of the famous sculptures that had already come to light in earlier trial excavations (like the sarcophagus of Meleager discovered in 1842 or the Naxian Sphinx discovered in 1861). In the first two months of excavation, crucial inscriptions had come to light. In the first full season of 1893, the altar of the Chians; the rock of the Sibyl; and the treasury of the Athenians with its carved metopes, inscriptions, and recorded musical notation for the ancient hymns to Apollo were found. In 1894 the beautiful statue of the Roman Emperor Hadrian's onetime lover and treasured companion, Antinous (see

fig. 11.1

), was uncovered, as were the treasuries of the Cnidians and Sicyonians. These discoveries were headline news in a world hungry for more from the ancient world. The hymns from the Athenian treasury were played for the Greek king and queen on 15 March 1894, at the Odeon in St. Petersburg on 11 May, as far as Johannesburg later that year, and even at the conference organized by Pierre de Coubertin in 1894 at which it was decided to restage the ancient Olympic games. Plaster casts of finds such as the Naxian Sphinx and the statue of Antinous quickly made their way to exhibitions in Paris, engendering continued amazement at the quality, skill, and sheer beauty of ancient sculpture. Such reactions were further fueled by the discovery, on 28 April 1896, of the famous bronze Charioteer that is now the centerpiece of the modern Delphi museum (see

plate 6

).

4

But not every day produced such finds. In 1895, despite moving 160,000 wagons of earth, nothing major was found. Nor did conditions at the site make excavation easy. Heavy rain frequently interrupted excavation, and considerable time at the end of each season had to be dedicated to constructing strong barriers to protect the site from rain, mud, and rockfalls. Winds so strong that they created dust storms could also blow up. The Greco-Turkish War interrupted excavation almost entirely in 1897. The journal bears witness also to a degree of exasperation among the French archaeologists that the local workmen claimed so many religious festivals as holidays, and the French correspondence shows ongoing difficulties in agreeing with members of the Greek Archaeological service present at the site about what constituted important finds and

what could be ignored. The increasing number of VIP visits did not help the progress of the excavation, nor did the continued criticisms levied by journalists and other archaeologists, particularly the German archaeologist Hans Pomtow. Pomtow had already published his own book on Delphi following his early trial excavations during the ten-year-long negotiations for the site. Now he continued to doubt French ability to undertake the task; criticized Homolle's hands-on style; and when, despite all this, the French team published a significant number of results in 1898, his review in the

Berliner Philologische Wochenschrift

indicated that scholars should forgive Homolle his inaccuracies given the mass of work he was attempting to cover.

5

By 1901, however, the main areas of the site had been uncovered. The wagons were shipped off to other French excavations on Delos in the Cyclades, and subsequently Thasos in the northern Aegean (although two can still be seen at Delphi today). The museum at the site that housed the finds, paid for by a Madame Iphigeneia Syngros, was inaugurated on

2 May 1903, and a big party was held to celebrate the end of the excavations. Five warships, three French and two Greek, were present in the harbor below; ten thousand locals were present in the area around the stadium; and a plethora of diplomats bore witness to the event in as fine an array of fashion as could be seen on the Champs Ãlysées. Homolle subsequently left, elevated to the position of director of the Louvre in France, and the dig house fell silent. Only the opening of the grand hotel “Apollo Pythia” in the new nearby village by 1906 gave an indication of the transformations still to come.

6

When Homolle and his team left the dig site, their plan was to prepare its “definitive” publication in five volumes along the lines already established for Olympia (

Olympia:

History, Architecture, Inscriptions, Statues, Small Objects

).

7

On the one hand, their excavation had been an incredible success: an extremely difficult dig that had returned to light the remains of one of the most important sanctuaries in the ancient world and produced some extraordinarily fine pieces of ancient sculpture alongside important architectural discoveries and endless inscriptions. Yet, on the other hand, there was a lingering feel of disappointment, which was in

part inevitable. The excavation had been conducted with ancient literary descriptions of the site literally in hand, and its progression had intentionally mirrored that of Pausanias's second-century

AD

tour-guide visit to the sanctuary to ensure the highest probability of identifying all the monuments he mentioned. When all the wondrous objects Pausanias alluded toâparticularly the temple sculpture and, even more disappointingly, the apparatus of the oracle (also the subject of other authors like Plutarch and Diodorus)âwere not uncovered, naturally there was disappointment, and not only among the excavators.

8

As one critic grumbled in response to the 1901 Delphi display at the Universal Exhibition, “the impression is sad, the reality a long way from any concept of beauty, and there is nothing to do but rely on one's imagination.”

9

The disappointment felt at the lackluster state of the physical site of Delphi at the end of the big dig prompted its director, Théophile Homolle, to attempt the reconstruction of one of its most famous monuments: the treasury of the Athenians. Almost all the original pieces of the building had been found early on in the first full year of the excavations, and the inscriptions that covered its wallsâparticularly the hymns to Apollo, the earliest musical notation in Mediterranean historyâquickly became world famous. In July 1902 Homolle wrote to the mayor of Athens, “For the Athenians of today, it would be a noble satisfaction to write their name alongside those who fought at Marathon and to inscribe, under the eloquent dedication which recalls one of the great events in Greekâand humanâhistory, a new inscription which will, for future generations, be a memorial to their unwavering faith towards the great accomplishments, glory and courage of their ancestors.”

10

The municipal council of Athens immediately voted to give 20,000 drachmas for the project and made Homolle a citizen of the city. In 1903 Joseph Replat, a skilled architect, was tasked with the reconstruction, which he completed not only thanks to his architectural knowledge of how the ancient stones fitted together, but also, perhaps more importantly, thanks to the piecing together of the different inscriptions covering large numbers of blocks in the treasury's walls, and thus dictating the relationship of those blocks to the building's architecture. The story

goes that Replat was so dedicated to his work at Delphi that, at the end of his active life, all he chose to exclaim was simply, “Delphi, adieu!”

11

The treasury was completed on 26 September 1906 and has remained one of the sanctuary's most impressive sights ever since (see

fig. 5.4

)

Yet much of the rest of the site was in chaos, with large depots of stones from the excavations piled helter-skelter. The museum, opened only in 1903, was leaking badly by 1906, and parts of the site were declared unsafe, not least thanks to the continued rockfalls from the Parnassian mountains above. In 1905 a series of massive rocks fell into the Athena sanctuary, and one of themâtoo big to moveâstill sits in the middle of it today, a continuing testament to the dynamic geology of the area (see

plate 8

). All these problems were the headache of the Greek Archaeological Service, which had taken over the running of the site, particularly the scholarly and diligent Antonios Keramopoullos and Alexandros Kondoleon. Keramopoullos published the first guide book to the site in 1912, and Kondoleon is remembered affectionately in the archives for his unique and unswerving dedication to Delphi, its preservation and study, which meant everything from chasing after soldiers who helped themselves to small museum exhibits, to subjecting new French scholars arriving at the site to a frosty reception until their skill and love for Delphi could be proven to Kondoleon's satisfaction.

12

But the French were not the only ones there: the German Hans Pomtow, active at Delphi before the dig big, and so critical of French efforts during it, returned on several occasions to conduct small excavations and publish finds and inscriptions (strictly in contravention of the French/Greek convention on the site).

13

World War I brought a halt to work at Delphi, and despite its not being on a front line, made it once again a rather unsafe place thanks to increased local sectarian violence: one French scholar of the time recalled seeing three severed heads on display in the local town square. The 1920s saw the emergence of a new generation of French scholars at Delphi: Robert Demangel; George Daux; and Pierre de la Coste-Messelière, under the direction of Charles Picard as director of the French School, and guided by Emilie Bourguet, one of the surviving figures of the big dig after Homolle's death in 1925. When I first visited the library of the

French dig house at Delphi in 2006, I was intrigued to find an old colonial pith helmet propped on top of the bookshelves, which, I learned, belonged to one of the most colorful Delphic scholars of the 1920s generation: Pierre de la Coste Messelière, who was never seen without it while working on the site. De la Coste-Messelière was a marquis, descended from the family of Charles VII, and had fought in World War I as a mounted cavalry officer, for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Following the war, he stumbled into the university lectures of Emilie Bourguet and become hooked on Delphi. Always immaculately dressed, pipe clenched in his teeth, he developed a love and sensitivity toward ancient sculpture that resulted in a number of crucial Delphic publications; he took to the battlefield again in World War II, was again awarded the Croix de Guerre, and later returned to work once again on the site (

fig. 13.3

).

14

The 1920s also saw the reconstruction of a second Delphic monument: the altar of the Chians (see

plate 2

,

fig. 1.3

). Just as the treasury of the Athenians had been reconstructed with money put forward by modern Athens, so too the modern-day islanders of Chios paid for the

reconstruction of the altar. On 12 March 1920 the Greek minister of public education informed the director of the French School, Charles Picard, that 10,000 drachmas had been collected and deposited in a bank account, at his disposal for the rebuilding of the altar, and reconstruction began the next month.

15

Greek cities of the modern world had begun to stake their claim once again on ancient Delphi, ensuring their monuments would once again receive the respect they'd garnered so many centuries before. In the same vein, in May 1927 the Greek lyric poet and playwright Angelos Sikélianos and his wife, the American Eva Palmer, launched the first modern Delphic festival, which sought to re-create the ancient Pythian games with gymnastic contests and the performance of tragedy (in that year, Aeschylus's

Prometheus Unbound

), bringing the world once again to Delphi.

16

But we should not underestimate the ongoing difficulties in getting to and living at Delphi at this time. The road from Arachova was not yet dreamt of, the road up from the port of Itea was still only in rough condition (see

fig. 0.1

). To get there from Athens in 1933 meant a slow boat from Athens to Itea that arrived at three or four in the morning, then waiting till later in the day for one of the few taxis that made the journey up to Delphi. And upon arrival at the dig house or the site, there was no electricity, and locals were still found washing their clothing in the oracular Castalian spring.

17