Delphi (30 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

This declaration of war against Rome was a threat the Romans could no longer tolerate. Landing in Greece almost immediately after Antiochus's sacrifice at Delphi, the Roman forces, under the control of Manius Acilius Glabrio, dislodged those of Antiochus and the Aetolian league from the their stronghold at the infamous pass at Thermopylae, the “bottle-neck” of Greece. It is testament to the fast-changing nature of alliances in this period that Philip V of Macedon, defeated by the Romans in 197

BC

, now fought, just six years later in 191, with the Romans against Antiochus. Equally so is the fact that Philip also fought alongside Eumenes II of Pergamon, who had become king on the death

of his father Attalus I in 197 (Philip had tried to conquer Pergamon less than a decade before, nearly capturing Eumenes' father several times in the process). Within months of the onslaught from this Roman, Macedonian, and Pergamene force, the Aetolians sued for peace. Antiochus remained to be dealt with.

7

To the Delphians, having seen Antiochus's proud arrival followed in such a short space of time by news of Glabrio's victory, the world must have seemed a very uncertain place. But they did know for sure now where their allegiances needed to be.

8

Between September 191

BC

and March 190, Glabrio not only seems to have turned over a series of confiscated Aetolian properties in the vicinity of Delphi to the “city and the god,” and made a series of changes to the boundaries of Delphi's sacred land, but also wrote a letter to the Delphians, saying he would support in Rome the sanctuary's return to its ancestral ways of governance and the autonomy of the city and sanctuary.

9

In response, the city of Delphi not only welcomed their “liberation” by the Romans, but engraved Glabrio's letter on the base of the statue they set up in his honor, along with a list of all the peopleâmostly Aetoliansâthey promptly chucked out of the city.

10

Glabrio's initiatives probably engendered some regional hostilityâparticularly his changing of land boundaries, which brought Delphi into conflict with its long-term local rival, the city of Amphissa (see

map 3

). His offer to the Delphians may well also have begun (or indeed been responding to) a tussle for power at Delphi between the city (which some sources intimate attempted to push Glabrio to give them sole control of the sanctuary and shut out the Amphictyony entirely) and the Amphictyony, who wanted Glabrio and the Roman Senate to restore the traditional Amphictyony/city divided system of control over the sanctuary.

11

But, for the moment, Glabrio had a more important enemy to deal with: Antiochus III. In 189

BC

, Antiochus was finally defeated by a combined Macedonian, Pergamene, and Roman force at the battle of Magnesia, with Eumenes II of Pergamon personally leading the cavalry charge that was crucial in bringing victory.

12

In 189

BC

, just as Antiochus was defeated, Delphi sent three ambassadors to Rome to confirm Glabrio's offer of the city and sanctuary's

independence. Spurius Postumius Albinus wrote in response to Delphi to confirm the Roman Senate's official decision to uphold Glabrio's offer. As a result, Delphi's Amphictyonic council was reformed so that, for the first time in its history, the Delphian representatives now chaired its meetings.

13

But on their way home, the Delphian ambassadors were murdered by Aetolians. Later that same year, Delphi sent two more ambassadors to Rome, this time to announce the creation of a new Delphic festival, the Romaia, in honor of Rome, and also to bring to Roman attention the murder of the previous ambassadors and point the finger at those responsible. The Senate commanded M. Fulvius Nobilior to search for the culprits, and G. Livius Salinator wrote to Delphi to confirm the Senate's acceptance of the new festival in Rome's honor, the text of which was inscribed publicly at Delphi on the base of Glabrio's statue, which was fast becoming the central notice board in the sanctuary for the developing relationship between Rome and Delphi.

14

In 189

BC

, therefore, Delphi was once again in a very different sort of limbo from that in which it had found itself at the beginning of the century. On the one hand, it had a degree of libertyâguaranteed by the Roman Senateâit hadn't had since the Aetolians had taken control of the sanctuary in the early third century

BC

, and indeed perhaps a degree of liberty it hadn't had in its entire history. On the other hand, it was still a small city without an army; it was in only partial control, with the Amphictyony, of the sanctuary. Its civic ambassadors had been murdered by Aetolians, it was surrounded by Aetolian communities or those in sympathy with Aetolia; and its livelihoodâthe sanctuaryâwas still to some degree dependent on Aetolian business. That position became even more precarious when the Romans, having again asserted their interests in Greece, decided again to leave. In 188

BC

, they withdrew, leaving behind no troops, veterans, garrisons, governors, political overseers, or indeed even any diplomats. Delphiâwhatever the Roman Senate had promised and Delphi had inscribed on its wallsâwas once again on its own.

15

Delphi did have one clear ally, Eumenes II of Pergamon. Like his father before him, and unlike other Hellenistic rulers, Eumenes II happily

pumped money into the sanctuary. In the 180s

BC

he sent slaves to help with the construction of Delphi's theater, another testament to the continuing popularity of the sanctuary's musical competitions at this time in that Delphi now had need of a dedicated stone-built structure in which to house the competitions and spectators.

16

In response, the Amphictyony were happy to recognize the status of asylia for the sanctuary of Athena Nikephoros in Pergamon and the Nikephoria games set up by Eumenes. In addition, Eumenes II was honored with statues in the sanctuary, one by the Amphictyony and one by the Aetolians, testament to their lingering presence at Delphi, especially since the statues were placed center stage on the temple terrace of the Apollo sanctuary.

17

We hear little about Delphi in the remaining years of the 180s and early 170s

BC

. On receipt of a gift of 3,520 drachmas from the Calydonian Alcesippus the sanctuary was happy to establish a festival celebration called the Alcesippeia.

18

The Rhodians were called in to arbitrate on a question of land border dispute between Delphi and Amphissa in 180â79

BC

.

19

Aetolian use of the sanctuary seems to have petered out after 179

BC

, and, in 178

BC

, the Amphictyony unusually called itself, in the inscribed list of delegates for that year's meeting, “a union of the Amphictyons from the autonomous tribes and the democratic cities”; this was thought to be not only a celebration of Delphi's newfound independence, but also a dig at the Amphictyons' former enemies, particularly the Aetolians and Macedonians.

20

A question to the oracle about an issue of colonization by the island of Paros in 175

BC

represents a distant echo of Delphi's almost continuous role in these processes back in the seventh and sixth centuries

BC

. Also in 175

BC

the father of the Delphian Eudocus erected a statue of Eudocus in the sanctuary, in honor of the latter's athletic victories.

21

Yet, at the same time, pressure was again building in the wider Greek world that would change Greece's, and Delphi's, future for good. In 179

BC

, Philip V of Macedon, having waged war against and then alongside the Romans, died. He had been slowly and successfully rebuilding Macedonian power within the constraints of burgeoning Roman influence. Yet in his last moments, he seems to have attempted to stop his son

from succeeding him. Perhaps it was for fear of what his son, Perseus, would attempt once on the throne.

22

Taking control despite Philip's final efforts, King Perseus of Macedon initially walked a careful diplomatic line, pacifying Rome and flattering Greece. Delphi too was flattered, as one of the sanctuaries chosen as the place of publication for Perseus's call for the return of all exiles to Macedonia, and for his treaty of friendship with the Boeotians.

23

Yet in 174

BC

, Perseus crushed a tribal rebellion against him in Macedonia and subsequently set off on a leisurely tour with his army through central Greece, which brought him to Delphi. His arrival was timed to coincide with the celebration of the Pythian games, Perseus grandly sweeping in to sacrifice at the sanctuary as part of the festival.

24

Perseus continued to use Delphi as a place for acts of public propaganda. He consulted the oracle in what was to become (although he could not know it at the time) the last ever consultation by an independent monarch of the oracle at Delphi.

25

Yet Perseus also used Delphi as the location for his more cutthroat activities, including the attempted murder of his enemy, and longtime Delphic supporter, King Eumenes II of Pergamon, who had, in 172

BC

, traveled to the Roman Senate to warn them of the threat Perseus posed to Roman interests. With the help of Praxo, the wife of an eminent Delphian who later became a priest of Apollo, Perseus set up an ambush on the road leading from the port of Cirrha up to Delphi. Eumenes' party was slain and Eumenes himself left for dead.

26

By 171

BC

, Rome had awakened to the threat Perseus posed to Roman interests in Greece. Delphi, in part because it had been a focus for Perseus's propaganda, in turn acted as a primary focus for the Roman articulation of Perseus's wrongdoings. In particular, the Romans focused on Perseus's armed participation at the Pythian festival in 174

BC

at a sanctuary whose independence was, at the end of the day, guaranteed by the Roman Senate. In addition, they focused on his attempted murder at Delphi of Eumenes II, a friend of Rome, as well as his wider alliances with the same barbarians who had invaded Greece and sacked the temple of Apollo at Delphi just over a century before. These grievances were inscribed and publicly displayed in the sanctuary at Delphi.

27

In the years that followed, Roman troops flooded back, this time under the command of Lucius Aemilius Paullus, to fight in what has become known as the Third Macedonian War.

28

On 22 June 168

BC

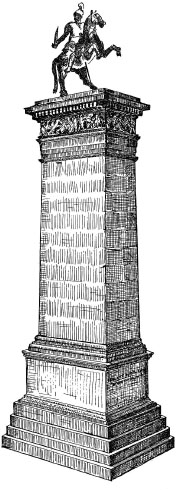

, Paullus crushed Perseus at the battle of Pydna, a victory that was commemorated most pointedly at Delphi. Perseus had been in the process of building himself another ten-meter-high statue at Delphi, intended as a victory monument in which a golden statue of him on horseback would stand atop a marble column, and be located on the temple terrace. It was unfinished when his hopes were crushed at Pydna. In a brilliant piece of propaganda, Aemilius Paullus chose to complete the monument, putting a statue of himself on horseback in place of that of Perseus, and adding a sculptured frieze around the base depicting his victory at Pydna (

figs. 9.1

,

1.3

). In addition he erased the Greek inscription already carved in anticipation of Perseus's victory and replaced it with his name, titles, and a short but pointed explanation in Latin: “de rege Perse Macedonibusque cepet” (“[that which] he took from King Perseus and from the Macedonians”).

29

Apollo is absent from Paullus's declaration: this monument is not about thanking the gods for victory, it is about making a political statement of that victory in the most public and forceful way possible. This new monument stood on the temple terrace of the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi in the area where the major monuments to Greek victory over foreign invading enemies had stood for centuries (see

fig. 1.3

). Yet this time it was a Roman general commemorating his victory over a Greek force, and in so doing preserving what Rome had guaranteed: Delphian independence and Greek “freedom.”

Yet the victory at Pydna also marks a critical moment in the nature of the freedom that Rome offered Greece. Rome abolished the Macedonian monarchy, replacing it with a series of republics. More widely, 168

BC

represents the tipping point for Greece (and the rest of the Mediterranean) in what political scientists call “unipolarity”: the arrival of Rome as the only political and military force in the Mediterranean. Rome had emerged victorious from the wars at the end of the third and beginning of the second centuries

BC

against Carthage, Macedon, and the Seleucid Empire. In previous Greek conflicts, it had subsequently completely

withdrawn. But after 168

BC

, there was to be no withdrawal. Greece's “multipolar anarchy” of the Hellenistic world was replaced by Roman unipolarity, which would be imposed on the country in an ever increasingly forceful manner.

30

Delphi had not only, once again, been an important factor in the events that had brought Greece ever more closely under Roman control, it had also been the place in which to make that transition clear through the dedication of the remarkable victory monument of Aemilius Paullus. But to what extent would and could Delphi's freedom continue in this new phase of Roman unipolar dominance?