Delphi (29 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

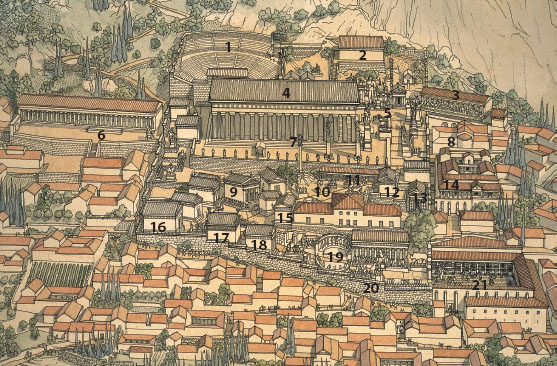

Plate 1

. A watercolor reconstruction of the ancient city and sanctuaries of Delphi with main areas labeled (aquarelle de Jean-Claude Golvin. Musée départemental Arles antique © éditions Errance) 1 Parnassian mountains. 2 Stadium. 3 Apollo sanctuary. 4 City of Delphi. 5 Castalian fountain. 6 Gymnasium. 7 Athena sanctuary.

Plate 2

. A watercolor reconstruction of the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi with main structures labeled (aquarelle de Jean-Claude Golvin. Musée départemental Arles antique © éditions Errance) 1 Theatre. 2 Cnidian lesche. 3 Stoa of Attalus. 4. Temple of Apollo. 5 Temple terrace. 6 West Stoa. 7 Naxian Sphinx. 8 Roman baths. 9 Athenian treasury. 10 Aire. 11 Athenian stoa. 12 Corinthian treasury. 13 Cyrenean treasury.14 Roman house. 15 Cnidian treasury. 16 Theban treasury. 17 Siphnian treasury. 18 Sicyonian treasury. 19 Argive statues. 20 Post-548

BC

sanctuary boundary wall. 21 Roman agora.

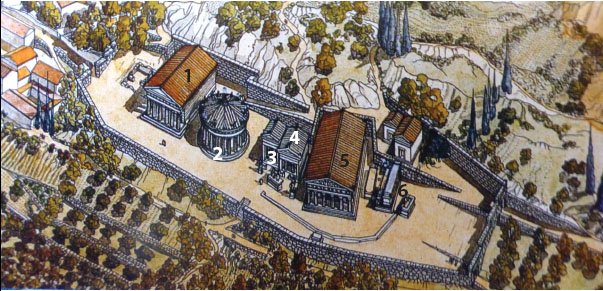

Plate 3

. A watercolor reconstruction of the Athena sanctuary at Delphi with main structures labeled (aquarelle de Jean-Claude Golvin. Musée départemental Arles antique © éditions Errance) 1 Fourth century

BC

temple of Athena. 2 Tholos. 3 Treasury of Massalians. 4 Doric treasury. 5 Sixth century

BC

temple of Athena. 6 Altars.

Plate 4

. The

Priestess at Delphi

as painted by John Collier 1891 (© John Collier, Britain 1850â1934, Priestess of Delphi 1891, London oil on canvas, 160.0 x 80.0 cm, Gift of the Rt. Honourable, the Earl of Kintore 1893, Art Gallery of Southern Australia, Adelaide).

Plate 5

. The remains of a Chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue dedicated in the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi, and subsequently buried in the sanctuary (Museum at Delphi).

Plate 6

. The Delphi Charioteer (Museum at Delphi).

Plate 7

. A view of Castri/Delphi painted by W. Walker in 1803 (© Benaki Museum).

Plate 8

. The still very visible remains of a rockfall at Delphi in 1905 at the temple of Athena in the Athena sanctuary (© Michael Scott).

PART III

Some have greatness

thrust upon them

“ Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice.”

“ Reader, if you are looking for something monumental, look around you.”

âEpitaph for the Delphic scholar Pierre de la Coste Messelière (1894â1975), which is on display at the French dig house at Delphi. The same wording was famously first used by Sir Christopher Wren in (his) St. Paul's Cathedral, London (1723).

9

A NEW WORLD

At the dawn of the second century

BC

, the Delphians found themselves in a curious limbo. On the one hand, their sanctuary was overwhelmingly still under the thumb of the Aetolians, who interfered in Delphic civic life, dominated many aspects of the sanctuary and its business, and even appointed informal “overseers” (

epimeletai

) to keep an eye on things in the city. The Delphians were at pains to honor the overseers (who seem to have been given rights even to keep herds of cattle on Delphic public land) on a regular basis.

1

At the same time, visitors to parts of the Delphic complexâparticularly the Corycian cave in the Parnassian mountains aboveâwere beginning to decline. And even the oracle, according to Parke and Wormell, can be shown to have had only one genuine consultation in the entire second century

BC

, despite the fact that the Delphians during that time, in a single inscription, granted proxenia to the citizens of 135 different cities in the ancient world.

2

And yet, on the other hand, the territory this small city controlled was larger than that of a number of central Greek cities. The surviving lists of those whose gave hospitality around the Greek world to the

theoroi

âthe messengers sent out from Delphi to announce its athletic and musical gamesâgrow longer than ever in the second century

BC

, testifying

to the importance and popularity of Delphi's contests. In 200

BC

, one of the winners, Satyrus of Samosâvictor as an

auletes

(flute player)âwas apparently so delighted with his win that he immediately played two impromptu concerts in the stadium at Delphi as a gesture to the gods and spectators. At the same time, far away at the Greek settlement of Ai Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan, a man named Clearchus was in the process of erecting a monument telling of his journey all the way to Delphi and back. The monument spelled out the purpose of his journey: to copy with his own hand the words of the Seven Sages inscribed on the temple of Apollo, so that his fellow citizens could benefit from their public display at home. As well, the Amphictyony had recently given the go-ahead to a near four-meter-high bronze statue of the people of Antiocheia, as well as to a statue of similar height for Antiochus III (to complement another statue of this king atop a horse already dedicated in the sanctuary), both of which were placed in a prime position to the west of the temple of Apollo.

3

As the century began, then, Delphi was not independent but increasingly cosmopolitan, in decline and yet never more popular.

But all this was about to change. In 200

BC

, as Delphi became less and less subtle in its call to be freed from its Aetolian “oppressors,” Rome was once again drawn into Greek affairs. King Philip V of Macedon, this time seeking to expand his territory by annexing parts of the Greek world belonging to the Ptolemaic (Egyptian) ruling family, had set his sights on the island of Rhodes, as well as on the city of Pergamon (see

map 1

). Pergamon was the seat of Attalus I, friend of Rome, Aetolia, and Delphi. Initially reluctant to fight Philip again, having just emerged from the Second Punic War against Carthage, Rome at first counseled peace to Philip. But soon enough, particularly after Philip had also set his sights on taking Athens, in October 200

BC

, Rome went to war again against Philip V of Macedon.

The resulting victories of Rome were based on the slogan “liberty for the Greeks.” Macedon was forced to withdraw back into its own kingdom. In May 196

BC

, at the Isthmian games, the herald proclaimed that the Roman Senate and consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus, had defeated

Philip V, leaving “free without garrisons, without tribute, governed by their ancestral laws, the Corinthians, Phocians, Locrians, Euboeans, Achaeans, Magnesians, Thessalians, and Perrhebians.” Flamininus celebrated the victory, or rather liberation, at Delphi. He sent his own shield along with shields of silver and a crown of gold, decorated with a series of poetic inscriptions, as dedications to Apollo. The Delphians in return later put up a statue of the general in the Apollo sanctuary.

4

Yet, almost as soon as the Romans had liberated Greece, they were gone. Despite staying in contact with the city of Delphi (as witnessed by a series of proxeny decrees for Romans inscribed in the sanctuary), by 194

BC

, there was not a single Roman solider left in Greece.

5

What brought them back was their one-time ally, the fading Aetolian league who were stillâbarelyâmasters of Delphi. In 193

BC

, just a year after the Romans had left Greece, the Aetolians rallied their allies, including king Antiochus of the Seleucid empire in the East (the same king who had recently been honored by the Amphictyony with an enormous statue of himself in the sanctuary). In October 192, Antiochus landed in mainland Greece with ten thousand men, five hundred cavalry, and six elephants. The king came to Delphi to offer sacrifice, and, in the spirit of the place which had, twice before, been the scene for defeats of forces invading Greece (the Persians and the Gauls), Antiochus proclaimed himself champion of Greek freedom against Roman domination (despite the fact that the Romans had proclaimed the freedom of Greece just four years earlier and subsequently left).

6