Death: A Life (25 page)

Happy Days with Maud.

I lowered my gaze. I could still remember the arch of Maud’s back beneath my hand, her arms thrown joyfully in the air, that go-hither look in her eyes as she was enveloped in the flames, her skin bubbling and bursting, her attendants running frantically around her. Oh Maud! How I wished you were with me now.

“If you admit that you gave her a little push, she’ll be saved, you know,” said Gabriel. “She’ll be able to spend the rest of her days in Paradise. Of course, you will be condemning yourself to extinction, but of course, is that not what

sacrifice

is all about?”

Gabriel turned obsequiously to God and bowed. A smattering of applause sounded through the Parliament.

It was all so absurd. Why did it matter if she fell or if she was pushed? Didn’t the forces that ruled the Universe have anything better to do than quibble over the final destination of some poor girl’s soul?

“We found a handprint on the back of her soul, you know,” said Gabriel, eyeing me carefully.

For the first time in my existence, I believe, I felt terror.

“But,” said Gabriel, unable to draw a reaction from me, “it was indistinct. You didn’t by any chance…help her on her way, did you? Maybe she was taking too long, being too indecisive, and you gave her a little…boost?”

I shook my head in denial. It was all I could do. In front of me, God, Jesus, and the Holy Ghost huddled together until they seemed to merge into one being—a blindingly bright bedsheet with a beard. They separated and stared long and hard at me.

“You are dismissed for now,” boomed God. “But don’t go leaving Earth anytime soon. We’ll be keeping an eye on you.”

As I hurried away, out of the Parliament, I heard a voice shout, “Jesus reigns in Heaven, bitch!” It was followed by the sound of a somewhat muted slap, as of a high five being performed between a ghost and a man with holes in the palms of His hands.

I stepped outside onto the cloudbanks and felt something trickling down my forehead. It was thick with perspiration. I was stunned. I had never sweated before. Only living things sweated and I wasn’t….

Suddenly I felt incredibly claustrophobic. The entire Universe stretched before me and yet I felt hemmed in by a monstrous, arbitrary feeling. I wanted to get back to Earth, away from this infinite inhumanity. I wanted to be surrounded by Life again, the dirty, doomed Life that I knew so well, where no one was all-knowing, where you could only be in one place at a time, where when you were dead, you stayed dead.

I stared frantically at the fields of screaming babies, the peepholes into Hell, the flagellants’ chambers, the thousands of angels balanced on the head of a pin.

I had to get out of there right away.

Addicted to Life

B

ack on Earth

I was wracked with doubt. What meant this endless procession of nights and days wherein I moved as if I had some useful purpose? Why was I forced to eradicate the things that made me happy? But in that question lay the real problem. Why was I trying to be happy at all? Ah, Life! That cursed bright flower had already thrust its roots deep within my being.

How I wished that I had the possibilities offered by even the most meager of human lives. The thrill of walking the tightrope of existence, of being in time, being in peril, being in the wrong, being in over one’s head, being in love. But being, it seemed, was not within my range.

The sight of a scarlet battlefield, which in the past had inspired in me a heightening of the senses, now seemed a dull and sterile prospect. Was it that I was bored? Once you have sent a billion importunate souls into the hereafter it would seem only natural to become jaded. But I knew what troubled me was something more than just otherworldly weariness. The act of freeing a soul from a particularly mangled corpse began to disgust me. I even began to look away when scooping out the soul. Coupled with the physical revulsion was the nausea of moral uncertainty I now felt. It had suddenly occurred to me that it might not be all that pleasant to die. After all, you didn’t die when you were ready; there were no announcements, no invitations, nothing. One moment you were on Earth and the next you were gone. It was all very depressing.

Why was I always finishing things, never starting them? I longed for new beginnings, not old endings. It was hardly surprising that I should begin to wonder whether I should retire; or rather, whether I

could.

What, though, were my prospects? I supposed I could return to Hell, but the gates were now automatic and needed no guarding, and the very thought of working for Father buying and torturing souls sickened me.

It was then, faced with the futility of my situation, that I began having mad, foolish thoughts. I started imagining Maud and myself sitting in a buttercup field, plucking up the kisses that grew upon our lips, with the sun streaming down and the buttercups singing to us in their strange buttercup language. We would put our heads down deep in the flowers and luxuriously follow the activities of the tiny insects crawling here and there in the forest of grass. And when the sun grew too hot, we would go into the woods where bluebells blanketed our every step. And we would be full in the completeness of our love, happy in the oneness of our being, and hopeful, one day, of seeing a little Death stumble into the world.

It was mad, but I just couldn’t shake it. I was Death, Destroyer of Life, and all I wanted was a cottage by a stream, a pot of hot soup on the stove, and someone to love me. I was emptiness incarnate, but I wanted to fill the void that was my being. Almost against my will I found myself collecting living things. I kept the souls of dead puppies just inside the Darkness so that no one could see them, and whenever I had a spare moment I would play with them. Yes, it was mad. Yes, it was obscene. But my hands started to shake with excitement when I held and stroked their soft, plush hair. I kept telling myself that an understanding of Life was fundamental in understanding myself. But who was I kidding? I was hooked deep. The monkey was on my back, and I didn’t even realize it. I was chasing the wizard and riding the dragon and thinking it was fine. It would take me many years to admit what I now know for sure.

I was addicted to Life.

I don’t know

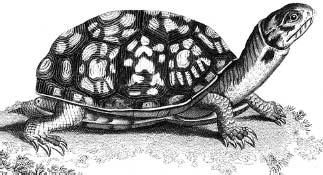

whether I had become more sensitive, or whether I was being tested in some way, but a sudden surge in dying helped me momentarily focus on my work and push these troubled thoughts to the back of my mind. It was the Romans who were largely responsible for this boom in dying. Never before in the field of human conflict had so much blood been spilled from so many by so few. Not only were the Roman soldiers equipped with the latest Iron Age weapons—iron filings to blind the enemy, branding irons to scald the enemy, clothing irons to rapidly de-crease the enemy—but they were also extraordinary trainers of war animals. After bombarding an enemy for days with lettuces and other greens, the famed War Tortoises of the Ninth Legion would be unleashed, creatures famed for the exceedingly slow but unstoppable swathe they cut through enemy lines. Looking back on it, I marvel at the Romans’ ingenuity, but at the time the sight of a soldier being slowly masticated gave me the shivers.

The Dread Roman War Tortoise: One Hundred Feet Long, Sixty Feet High, Lapsed Vegetarian.

The Roman engineers were no less brilliant. They defeated the underground kingdom of Carthage—so long a thorn in Rome’s side—by first raising it to the ground and then destroying it. What’s more, the bloodthirstiness of the average Roman citizen was unequaled. Orgies mingled with executions, wine with poison. It was a bloodbath, a slaughter sauna, a Jacuzzi of gore.

The Roman leaders were extremely difficult to deal with. I remember the indecisiveness of Julius Caesar when he was faced with crossing the Rubicon. Thousands stood ready to be slaughtered, and I had steeled myself for the task, but Caesar was mystified as to how he could transport his pet chicken, pet fox, and pet bag of grain across the river in his little one-man boat without the fox eating the chicken or the chicken eating the grain. As it was, the fox died of dropsy, the chicken was sacrificed, and the bag of grain was eventually made praetor by the emperor Caligula shortly before being eaten by Consul Incitatus, the emperor’s horse (the children’s song “Old Caligula Had a Senate” was one of the most popular of the age).

If they weren’t being indecisive, the Roman emperors were paranoid delusional.

“Who sent you?” asked Emperor Tiberius when I appeared to his soul.

“No one,” I said, through gritted teeth. “I am Death.”

“Was it Naevius Sutorius Macro? Or Tiberius Gemellus? Yes, yes, my own grandson, he sent you, didn’t he?” He drew out his sword’s soul from the soul of its scabbard and waggled it in front of my face. What was I doing here?

“Now look,” I said, struggling to instill some understanding into the man, although finding it hard enough to convince myself. “I am the End of Days, the Destroyer of All Things!”

“Or was it Gaius Caligula?” continued Tiberius, pacing back and forth frantically. “Yes, he would do something like this.”

“Do something like what?” I said. My patience was wearing thin. “You died peacefully in your sleep.”

“I’m sure that’s what you’ll tell the people, isn’t it?” crowed Tiberius. “Died in his sleep, happily ever after! Then how do you explain the position of that pillow?” He pointed at the pillow on which his body’s head rested. “I was smothered to death.”

“But it’s

beneath

your head,” I said, growing infuriated. “Your head is on top of the pillow, how could you have been smothered with it?”

But Tiberius’s soul was not listening. “I should never have poisoned you, Germanicus! If only Drusus was here to see this infamy, he would avenge me. Why did I order Sejanus to poison him? Or maybe he never died. Maybe it was Drusus all along, who killed me in revenge for my ill treatment of Livia Julia, who betrayed me to…”

This went on for some time, although I finally tricked him into hiding in the Darkness by pretending the Praetorian Guard were about to burst into the room to torture his soul.

Speaking of the Darkness, I had noticed changes in it, too. It lagged behind me and had trouble digesting souls. Although it was still as black as night, there was somehow something less dark about it. Admittedly you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face when you were wrapped within it. But you

could

now imagine that a hand might be in the general vicinity of your face. This was worrying.