Death: A Life (29 page)

The Clinic

I

awoke

in an unfamiliar room. The walls were black. I felt all warm and fuzzy inside until I remembered what had happened to the puppy. And then a sickness entered me, and a familiar cold fell around me.

I saw that the kitten was sleeping next to me. I picked it up and it purred. It was warm, and I rubbed my cheek against its soft fur.

“Ahem.”

There was a man sitting in the shadows across from my bed.

“How are you feeling?” he said.

“I feel fine,” I replied. Everything felt slightly unreal.

“Hmm,” he murmured, displeased. “Well, don’t worry, it’ll get worse.”

“What?”

“It’ll get worse. We’ll soon have you feeling terrible again.”

“But I don’t want to feel terrible.”

“Yes, you do. And you will.”

I looked around. There was a desk and a chair and a closet and a window.

“Who are you?”

“I’m a doctor.”

“Where am I?”

“You’re in a special facility, the oldest in existence, for the treatment of psychological disorders.”

“Psychological disorders? But I assure you I feel fine.” I rubbed my face against the kitten face again. It comforted me.

“That is the problem.”

“What do you mean?”

“We will need to monitor you carefully, and we will probably need to give you some toxification drugs.”

I started whistling.

“And a banshee will be here in a few minutes to wail at you.”

I smiled.

“Do you understand? You’re a very lively person. This needs to change.”

The kitten had woken up and was batting at my leg with its paws.

“You’re fine for now, but I think you’ll start to feel some more extreme things soon. Moments of euphoria, inexplicable instances of elation.”

He was right. I felt happy. Despite my strange surroundings I felt very, very happy.

“What have you been doing in the last few days?”

“Oh,” I said, and tried to recollect. “I’ve been playing with my kitten and with my puppy. I’ve been going for long walks, breathing in the air, waving at all the little birds.”

“And what did you do before that?”

“I was with someone. Someone who I liked very, very much. But I can’t remember who…”

“No. I mean before all this happiness. What do you remember?”

I thought back. All I could remember was blackness, emptiness, nothing.

“Nothing,” I said.

“That’s very good. Hold that image. What would you like to be doing now?”

I thought, and slowly the answer swelled within me, building in size, growing and growing until it was a gargantuan wave about to break with indescribable force.

“I want to skip and live and be happy.” I gasped. “I want to see and speak and climb trees and never come down. I want to paint my existence on the map. Straight onto the map. In glitter paint.” I took a deep breath. “And I want to fly kites. Fly kites high into the rainbows. Ride unicorns wildly through the…”

I paused. Something was scratching at the back of my mind. But the feeling was submerged as the swell rose again. I jumped up on the bed.

“Control yourself, Death,” cried the doctor, but I was too busy bouncing up and down to heed his calls.

“I want a room of feathers, and bright balls, and soft, squeezy objects that never hurt if you drop them on your foot. I want whimsical stories and joyful operettas, I want lightness, and happiness, and love. I want…I want…I want…Maud?”

Suddenly it all came flooding back.

“Where is Maud?” I asked frantically. “What have you done with Maud? Where is her body? Where is her soul?”

“Nurse!” the doctor called, and a burly Black Wraith materialized in front of me and knocked me onto the bed and held me there. I cried out for Maud. Desperately, hungrily, insatiably. I thought of Puppy, and then Maud. O Maud! Not again. You were meant to live this time.

We

were meant to live this time! Suddenly bluebirds sprung up in front of my vision. I tried to grab them but I couldn’t quite reach them. They perched on my body and twittered away, singing such sweet, sweet songs. I never felt the needle.

All the doctors

at the clinic were white-coated, faceless beings who carried stethoscopes around their necks despite having no ears in which to wear them. They were indistinguishable from one another and seemingly interchangeable. All carried a certain disinterested air about them that filled one with an immense sense of dissatisfaction. This, I gathered, was part of the healing process.

Dr. Faustus, Founder of the Clinic, Had Been Disbarred for Malpractice, Malfeasance, and Malevolence.

At my second interview, the doctor assigned to me told me that my record showed that I was thoroughly selfish, undisciplined, and immature and that he would not tolerate any misbehavior on my part at all during my stay. My kitten had been taken away from me. He said that I was there to become enthusiastic about dying again. The pangs of misery I had previously felt about Maud had been replaced by a quite unjustifiable optimism. It seemed to me that no sooner would I leave the clinic than we could begin things again, just as they had been before. Sitting in the doctor’s study, I was perversely happy with the thought of a new start.

“You’ve been spending a lot of time in the company of humans, haven’t you?” he said, flicking through my file.

“Yes,” I replied. “That’s my job.”

“But have you or have you not been fraternizing with humans on an extracurricular basis?”

“Occasionally.”

“If you’re not honest with us, Death, we can’t help you.”

“Perhaps I don’t want to be helped.”

“Oh, I think you want to be helped, even if you don’t know it. How often have you been carousing with humans, talking with them, spending excessive amounts of time with them?”

“Once or twice a century.”

“Be honest now.”

“Four or five times a century.”

“Death…”

“A decade.”

“Death…”

“A day.”

“You do know humans are highly toxic?”

“What do you mean?”

“Life,” said the doctor coldly. “Humans are positively teeming with it.”

“Well, yes, that’s why I like spending time with them,” I said. “What’s wrong with a little Life now and then?”

“A social life often precedes a biological life.”

I didn’t understand, and the doctor didn’t bother to explain but beckoned me to lie down on the table in the room. He put on his stethoscope, clipping it where his ears should have been, and began listening to my chest.

“Now, I want you to think about Life,” he said, his head still close to my chest. And so I did. I thought of fresh air; and green trees; and bounding, leaping creatures; and above all someone to share it with. Maud, Maud, Maud. Suddenly the creature in my chest returned. The creature that wanted to escape.

“Oh dear, oh dear,” the doctor said to himself. “This is not good at all.”

“What?” I asked, shaken from my reverie.

“You’ve developed a severe physical dependency on Life. It’s progressed further than I’ve ever seen. You’re very lucky to still be Death.”

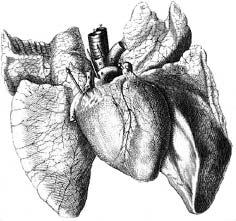

“But that’s preposterous,” I spluttered when suddenly the doctor, in one swift motion, thrust both his hands into my chest. There was some wrenching and twisting, a squelching sound, and a strange feeling of butterflies fluttering in my stomach. The doctor grunted and strained, and eventually, there was a loud pop, and he fell backward. His hands were clutching a still-beating heart.

“I bet you didn’t know you’d grown this, did you?” His empty face leered triumphantly.

I stared at the heart. It was beating in and out. Blood spurted from its severed arteries. So that’s where the thumping noise had been coming from. That’s what had been trying to escape into my mouth.

Heart: In the Wrong Place.

“First you’ll grow a heart, then a nervous system, and, if you’re not careful, flesh and blood too.”

He peered at my forehead.

“It already looks like you’ve developed sweat glands. Is that what you want, Death? To be able to sweat?”

I reached out to the heart, but as soon as my fingers touched it, it went into a spasm and stopped beating.

I allowed myself to be taken to a small black room in which lay a mountain of soft toys. There were teddy bears, and elephants, and dolphins, and baby humans, all made from the softest, plushest fur. The doctor told me that I wasn’t allowed to leave the room until all the animals had been torn apart. The door slammed shut and I was left alone. The hours passed. I did not rip the toys apart. Instead I arranged them in order of size, gender, and likelihood of compatibility. When the doctor came to check on me, he shook his head in disappointment, and when he later discovered that the number of stuffed animals in the room had in fact

increased,

I was locked in my room under close observation.

The clinic

sat on a lonely promontory located in the shadow of the mountain of Purgatory. I was told that it had been specifically designed to appear in a different way to each patient, as an aid to his or her rehabilitation. For instance, if the personification of Happiness arrived at the clinic suffering from a melancholy ailment, he might see himself attending a beautiful marble building bathed in sunlight and warmth, in an attempt to lift his spirits. For me, however, the clinic was quite different.

To my eyes, the clinic’s main building was black and wretched and caved in on itself like a collapsed lung. The grounds seemed to have been carefully devastated to promote thoughts of maximum wickedness. There were stony ravines and dense bushes of thorns, two small churning lakes of fire that belched out molten rock, several wide pastures of rusty nails, and a swamp full of loathsome creatures with needle-sharp teeth into which I was encouraged to push things. It was hoped that this would inspire within me the longing for pain and suffering that I had lost.