Death: A Life (20 page)

“That’s it?” I asked.

“Well,” he said, scratching his horns, “sex and long walks.”

I asked Mother the same question. She blushed. “Well, when two people like each other very much…”

“Yes,” I said eagerly. This sounded more promising.

“They have sex.”

When I bumped into Urizel, my old angel friend, who was still guarding the muddy remnants of Eden, I asked him the same question. He pulled out a guidebook entitled

The Only Planet Guide,

and after flicking through a few pages declared, “Love is, on the one hand, a mechanism for surveying and thereby rendering problematic particular relationships between bodies, and on the other the creation of a reflexive consciousness of self-identity involving manipulation of symbolic representations of the self.”

“You mean…,” I asked, as Urizel flicked to the glossary section at the back.

“Sex, apparently.”

What Is This “Love”?

I remember I had even asked God about it, back when He had still been around.

“Why do humans ‘love,’ Lord God Sir?”

“Aside from the sex?” He boomed.

“Yes.”

“And the long walks?”

“Yes.”

“Well, there are as many reasons for love as there are stars in the sky.” God gestured as if to look at the sun. “Is that the time? I really must be off.”

There was a pause, but the divine light remained.

“God?” I asked.

The light didn’t answer.

“God? I can still see You. You’re still here.”

“Damn this omnipresence!” He boomed.

But if love was simply about sex, why did I feel it was about so much more?

Maud’s increasingly

frequent visits provided welcome breaks amid the frantic Classical period. It was an era of great innovation among humans, which always meant plenty of work for me.

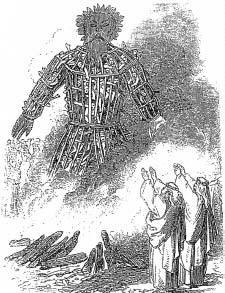

In England, the Druids had finally perfected the art of human sacrifice, tenderizing their subjects with a combination of ritual torture and atonal folk singing, and seasoning them with just the right amount of parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme. Indeed, the Druids greatly popularized sacrificing and were credited with taking it off the altar and into the home.

Druids: Loved to Barbecue.

Elsewhere, legal reforms swept society, such as those instigated by the Greek lawgiver Draco, who devised the “one strike and you’re out” judicial system, calling for execution as the punishment for all crimes. Upon seeing the reoffending statistics plummet, Draco came to the conclusion that since all crimes were committed by the living, the only crime-free society would be one consisting solely of the dead. It was an idea way ahead of its time and would have succeeded if only his advisers had not suggested that he lead the way into this peaceful crime-free future. The collective sigh of relief upon his death sank ships as far away as Crete.

Meanwhile an economic revolution was taking place under the guidance of Croesus, the king of Lydia, who had invented coinage and thus made property much easier to steal. I remember overhearing the argument as he tried to persuade his minions to implement the radical changes.

“But this isn’t the same as a cow,” exclaimed the Master of Barter looking at one of Croesus’s gold coins. “Where are its udders?”

“No, it’s not

actually

a cow,” explained Croesus. “It’s worth the same as a cow. This way you don’t have to run away with a whole cow when you’re raiding the Scythians.”

“How can it be worth the same as a cow if it doesn’t have any udders?”

“Well, it’s like this…”

“It doesn’t taste like a cow either,” grimaced the Master of Barter, biting into the coin. He winced. “It tastes much more painful than a cow.”

“No, look…,” said Croesus, but the Master of Barter was on a roll.

“And where’s its tail? No one’s going to think this is a cow if it doesn’t have a tail.”

“Guards!” cried Croesus, whose patience did not extend as far as his credit. The Master of Barter was swiftly garroted, the first of many fiscal tightenings to occur in Lydia that year.

Not far away, artistic developments were being furthered by the insatiably bloodthirsty Assyrian Empire (which had been voted “Best Empire of the Year” for 103 years in a row by subscribers to the

Assyrian Supplicant,

a hung, drawn, and quarterly). Their greatest ruler, Ashurnasirpal II, had become obsessed with the relationship between the artwork and the viewer in his chosen medium of expression—impaling. Working months at a time, in campaigns ranging far into Asia, he displayed a remarkable aptitude for compositional effects that reduced the distance between spectacle and spectator until one was hard to differentiate from the other.

His finest piece,

Untitled # 65422 (Impaling),

showed a remarkable sharpness of line and sag of body. It was praised for its figurative suggestiveness and remarkable lack of ambiguity by the Kassites, the Elamites, and the Cimmerians, whose long-preferred oeuvre of “not bleeding” and “avoiding conflict” Ashurnasirpal overthrew during his masterful “red” period.

Dominated by Verticality, Ashurnasirpal’s Unique Visual Rhetoric Was Interformative, Transfictive, and Very, Very Painful.

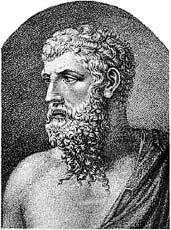

Nevertheless, it was the Greeks who best personified this new age of scientific invention and theoretical research. Nowhere was this more the case than at Plato’s Academy. Plato was the author of a plethora of popular tracts.

On the Soul, On Sensation, On Respiration, On Top of Old Smokey,

and

On and On with Plato

had all been bestsellers in both slate and papyrus editions. With the profits he had set up his Academy, a safe haven for the philosophically inclined, whom the general populace thought louche, hairy, and prone to saying awkward things at dinner parties. Indeed, Plato’s belief that it was only through the method of dialectic that pure reason could operate was openly criticized as being “girlie” by the rival monologist school of Isocrates, who propounded the dictum that the only intelligent conversation one could have was with oneself.

The Academy was home to cutting-edge research in every field. Loud explosions could be heard emanating from the school, as the mathematician Archimedes attempted to calculate his law of buoyancy in a lead-lined bathtub buried deep beneath the ground. Similarly the animal psychologist, Aristophanes, accidentally discovered the world’s first joke while inquiring into the hitherto mysterious motivations of pathway-traversing fowl. The results, read out in a paper to the academicians, caused such convulsions (later diagnosed as “laughter” by Hippocrates) that Aristophanes was believed to be a witch and was set on fire.

The philosophers may have thought hard, but they also played hard, and the Academy soon developed a reputation as a wine-soaked party college. Astronomy classes sought to pinpoint those stars that only revealed themselves when the viewer was drunk. Geometry classes attempted to understand the sudden increase in the earth’s revolutions after an amphora of wine had been imbibed, while Ethics classes considered the least offensive places in which to vomit (this was also covered in Retcheric).

The debauched lifestyle of the philosophers enraged prudish Athenian society, and when Philip of Opus, the Academy’s music instructor, composed a groundbreaking new dirge entitled “Fuck the Polis,” battle lines were drawn.

Pericles, himself a great political innovator and the democratically elected dictator for life of Athens, decreed that he would tear down the Academy and construct a giant new building on the site—the Acropolis—which would be open only to idiots and nonthinkers. He even had the Academy’s top sage and mixer of drinks, Socrates, imprisoned and sentenced to death for refusing to empty his mind of all thoughts.

Philip of Opus: Philosopha with Attitude.

As it was, Pericles needn’t have bothered. The Academy was ultimately destroyed by a vast explosion, the result of Archimedes’ attempts to square the circle, and Socrates died soon after, while attempting to incorporate hemlock into a new drink that he named the “Politan.”

When I met Socrates, he was remarkably calm. I asked him how he could be so serene even when facing me, and he replied that he had studied his life and was happy with it.

“The unexamined life,” he said, as the Darkness consumed him, “is not worth living.”

I didn’t have time to ask him about the unexamined Death.

By then

almost all the mythical creatures had disappeared, and those that remained were having a hard time adapting to this new, more rational world. The last Sphinx had fled Egypt on a boat to Greece, posing as both the ship’s cat and first mate. When it arrived, it immediately became swept up in the philosophical fashion of the country. Combining the incessant questioning that defined the Socratic Method with a healthy carnivorous appetite, the Sphinx came up with a deadly riddle—“What has one voice but walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three legs in the evening?”—that it would spring on unsuspecting Greeks as they went about their daily business. Failure to answer correctly, or within the allotted time period, or if there was any pause or hesitation at all, would result in the Sphinx biting the answerer’s head clean off.

A frightened populace implored the remaining members of Plato’s Academy to come up with a solution to the Sphinx’s riddle. Hippocrates, the father of medicine; Herophilus, the father of anatomy; and Galen, the father of experimental physiology, began by removing two limbs from a cow at midday, and then attempting to reattach one of them again in the evening. The results were grisly, and the various solutions to the riddle rarely survived. Work soon shifted to ponies, and then deer, and eventually a collection of hobbled and mutilated animals were paraded in front of the Sphinx. None passed muster, although all were eaten.