Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (41 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

Upon recovery from a severe illness, as was also done upon

the birth of a child and a safe return from pilgrimage to Mecca, a sheep was

sacrificed as an expression of thankfulness and gratitude to God for restored

health. If wealthy, the sick person who had recovered showered gifts and favors

among the members of his extended household, including his officers, doorkeepers,

irregulars, conscripts, cooks, tasters, muleteers, grooms, torchbearers, as

well as the homeless and destitute. He also distributed money among the poor;

had several orphan boys circumcised; gave each of the boys into the custody of

a master craftsman, or a teacher; and dressed them in a nice suit. The same

gratefully recovered man could also find homes for orphaned girls and provide

them with new clothing. He could also construct stone pavement over a road; dig

gutters to relieve a town from flooding and mud; build shops, coffeehouses, and

homes; and establish his property as an endowment for the establishment or

upkeep of a charitable foundation.

If the illness worsened and the sick person became

convinced of his death, he made his will in favor of his son, or any other

individual, in the presence of two or more witnesses. If the ailing man was a

person of status, wealth, and power, he summoned the ulema, notables, and his

subordinates to compose his last will and testament. These declarations would

include a request for where he should be buried, how much of his money could be

distributed among those who had served him, and whether any of his money could

be used to erect a monument or even a fountain at his tombstone. Many people

bequeathed some of their money to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. In some

cases, the dying man freed his slaves, bestowing on them and his servants gifts

and gold pieces. He also appointed his executor.

As the hour of death arrived, the family sent for a man who

could recite the Quran. He was asked to read in a loud voice the Ya Seen (Ya

Sin), or the 36th chapter of the Quran, which has been branded by some as the

heart of the holy book. It was believed that hearing the Ya Seen allowed the

departing spirit to calm itself and focus on the coming journey. Others present

also read prayers in an audible voice. At times, the sick person was encouraged

to recite the words of remembrance and forgiveness. Men of religion always

recommended, if at all possible, that a Muslim’s last words be the declaration

of faith: “I bear witness that there is no God. I bear witness that Muhammad is

the messenger of God.” In certain instances, when a person was on the point of

death, the people present poured sherbet made of water and sugar down his

throat.

As soon as the person died, his eyes and mouth were closed.

The dead person’s big toes were “brought in contact and fastened together with

a thin slip of cloth, to prevent the legs remaining apart.” The body was then

temporarily covered with a sheet. Perfumes were also burnt near the body of the

deceased. The local imam, or any other man of religion who was present,

encouraged the family to remain calm and accept a fate that could only be

determined by God who gave life and took it away. The imam also encouraged the

family to pray for the departed and to begin preparations for the burial.

Although Islam discouraged loud wailing and lamentation, an outpouring of grief

followed.

Muslim tradition required burial of the deceased as soon as

it was humanly possible, because it was not proper to keep a corpse long in the

house. If the person had died in the evening, the shrouding and burial had to

take place before midnight; if, however, he/she had died at a later hour, the

deceased was buried on the following day. Prior to burial, the body was washed

with warm water— usually by a member of the family, a close friend, or an

acquaintance. Ottoman women were always washed “by their own sex.” Professional

washers, both men and women, also were available to wash and shroud the body

for a fee. Every effort was made not to wash the body on flat ground because

the water could spread over a wide surface. Popular belief held that it was a

bad omen to walk on such water. Toward the end of the washing ceremony, camphor

and water were mixed and put into several pots and poured “three times first

from the head to the feet, then from the right shoulder to the feet, lastly

from the left shoulder to the feet” of the deceased. Every time the water was

poured, the declaration of faith was repeated by the person washing the body or

an individual present at the ceremony. If the dead had been killed as a martyr,

he could be buried in the very clothes he had died in.

After bathing the body and drying it with a clean piece of

cloth, “several balls of cotton wool were covered in calico and soaked in warm

water, to be inserted in the seven orifices of the body.” Cotton wools were

also placed between the fingers and the toes and also in the armpits. The

mourners then placed the deceased in a shroud (

kefen)

. For men, this

consisted of three pieces of clean white sheets, large enough to conceal the

entire body, and for women five pieces of white garments. The color of the

shroud had to be white. The

kefen

for both men and women was perfumed

with scented water or incense. At times, “pepper, spices, and rose-water” were

also “put in other crevices.” Attendants then laid the body in a coffin with

the face of the deceased facing downward. The coffins of men were distinguished

by a turban and those of women by a coif. If the deceased had been a girl and a

virgin, the rich and powerful families set garlands and boughs of oranges on

the coffin as they carried it to the cemetery. The coffin transported the body

to the burial site where funeral prayers were read. Sometimes before the

funeral procession, the family of the deceased hired a group of mourners who

proceeded through the streets at night proclaiming their grief with the cries

of mourning.

During the burial ceremony, only the male relations and

male community members could accompany the body to the cemetery. While men

participated in the funeral procession, women stayed home and mourned in the

privacy of the harem. Christians, Jews, and “foreigners were also excluded.” An

imam or a member of the religious class led the procession to the cemetery by

walking in front of the coffin. Other members of the religious establishment

walked on either side of the coffin. Mourners walked behind. While escorting

the body, the mourners remained silent. Islam discouraged carrying candles,

shouting the name of God, weeping loudly, playing music, or even reading the

Quran. Thus, “no external signs of mourning” were used by the Ottomans “either

for a funeral or subsequently,” nor were “periods of seclusion observed by them

on the death of a relative.” “Excessive sorrow” for dead children was “considered

not only sinful, but detrimental to their happiness and rest in Paradise.” It

was, however, “an act of filial duty to mourn consistently for lost parents,

and not to cease praying for their forgiveness and acceptance with Allah.” The

coffin “was draped with a red or green pall over which were spread blue cloths

embroidered with gold thread and silk.” When the mourners passed a mosque or a

shrine, they set the coffin down and offered prayers for the deceased.

Once the funeral procession had reached the cemetery,

family, friends, and acquaintances gathered to pray as the prayer leader or the

imam stood in front of the body of the deceased facing away from the mourners.

After the prayers had ended, “the lid of the coffin was removed before it was

lowered into the earth.” The shrouded body was lifted out of the coffin while

prayers were recited and was placed in the grave still wrapped in a

kefen.

The

body of the deceased had to be positioned in a recumbent posture at right

angles to the

kibla

(Arabic:

qibla)

or the direction of prayer

towards Mecca. In this way the body would face the holy city of Mecca if it

turned to its side. This placement enabled the faithful to have the same

physical relationship with Mecca in both life and death.

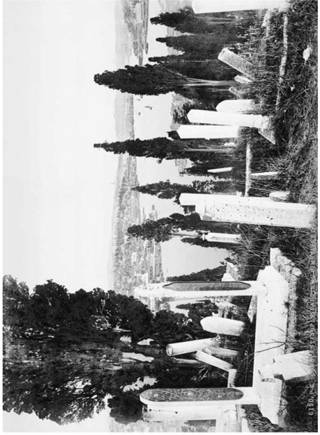

Cemeteries were located outside cities, towns, or villages,

and were not demarcated by walls, fences, and gates. Every attempt was made to

bury the dead in a beautiful cemetery amid flowers and cypress. Thus, one of

the largest cemeteries in Istanbul stretched along the slope of a hill

overlooking the blue waters of the Bosphorus and was densely shaded by old

cypress trees. Not surprisingly, the locals used the cemeteries as a park. It

was not unusual to find a Turk smoking his pipe or

chubuk

“with his back

resting against a turban-crested grave stone,” the Greek spreading “his meal

upon a tomb,” the Armenian sheltering himself “from the sunshine beneath the

boughs” that overshadowed “the burial places of his people,” “the women”

sitting “in groups” and talking “of their homes and of their little ones,” and “the

children” gathering “the wild flowers” that grew “amid the graves as gaily as

though death had never entered there.”

Several days after the funeral, women of the household

visited the cemetery and uttered lamentations over the grave. Once they had

expressed and released their grief and sorrow, the female mourners left food

offerings on the grave. There was no prescribed clothing for a mourning

ceremony, but men generally wore a coat in a somber color such as black or brown.

Cemetery overlooking the

Bosphorus and Istanbul.

When an Ottoman dignitary or high official passed away,

funeral procedures followed the official Hanafi rite. The body was laid out and

an

iskat

prayer was recited.

Iskat

was “alms given on behalf of the

dead as compensation for their neglected religious duties.” The body was then

washed, wrapped in a shroud, and placed in an ornamental coffin for “transport

to a mosque for prayers.” Viziers, ulema,

şeyhs,

notables, and

dignitaries assembled and carried the body to the mosque of Aya Sofya, while

muezzins and

dervişes

recited prayers and litanies. At the mosque,

a ritual prayer was performed. The funeral procession then continued with the

coffin carried to its final resting place at the cemetery. At the cemetery,

tents were set up and the holy Quran was recited by men of religion as well as

dervişes

for several days.

Each grave “was marked at the head by a single stone, about

fifty centimeters high, either cylindrical or uncut.” A person of wealth and

power was buried “in a rectangular marble tomb, a round marble column as high

as a man at the head, topped by a sculpture of the Turkish headgear appropriate

to the rank of the deceased.” The column was usually inscribed with Arabic

inscriptions from the Quran. Occasionally “instead of a column, the headstone

was a marble plaque about a hand span in width and as high as a man and again

carved with inscriptions.” Women’s “gravestones were carved with flowers and

verses of hope and if a headstone fell it was considered unlucky to set it up

again.”

Except as a special privilege, which could apply only to

sultans, dead bodies could not be interred in a mosque, church, or synagogue,

or even within the town or city, but rather in cemeteries in the suburbs where

the Muslims, Christians, and Jews had their own separate graveyards. In unique

circumstances, particularly when the body of a slain sultan was involved, the

internment could assume a significant political meaning. After Murad I was

killed on the battlefield of Kosovo Polje in 1389, his vital organs were

removed and buried in a mausoleum on the banks of the river Llap

(Serbo-Croatian: Lab; Turkish: Klab). His body meanwhile was carried to Bursa,

where it was buried at the courtyard of the city’s Great Mosque. Miloš Kobilić

or Obilić, the Serbian “hero” who assassinated Murad I, was interred in a

grave at a monastery a short distance from the sultan’s resting place. Nearly

three centuries later, the mausoleum of the assassin was “lit with jeweled

lamps and scented with ambergris and musk” and “supported by wealthy endowments

and ministered by priests who played host to passing visitors” and pilgrims. In

contrast, the mausoleum grave of the Ottoman sultan “was besmirched with filth”

and excrement, because the local Serbs used the royal tomb as a privy and

defecated on it to insult the Turkish invaders who had occupied their homeland.

To protect the royal mausoleum from future assaults, an Ottoman official

ordered the construction of a huge wall with a gate around the tomb “so that

people on horseback could not get in.” Five hundred fruit trees were also

planted and a well was dug. A keeper was appointed to live there with his

family so that they could care for “the silk carpets, candlesticks, censers,

rose-water containers and lamps” that furnished the mausoleum.