Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (40 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

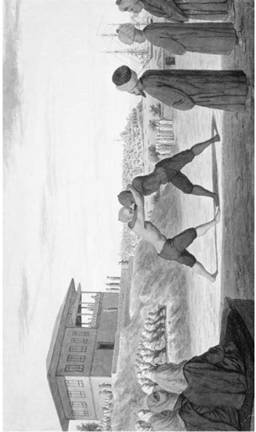

Kirkpinar, on the outskirts of Edirne, was the first site

of Ottoman wrestling competition. The area also served as a hunting ground for

Ottoman sultans. The first Kirkpinar wrestling tournament was probably held in

1360/1361, during the reigns of the Ottoman sultans Orhan and Murad I. Today,

yagli

güresh,

or oil wrestling— where young men compete in leather shorts, their

bodies shiny and slippery with oil—remains one of Turkey’s most popular

national sports. As in Anatolia and parts of the Balkans, in Egypt too, men

stripped themselves of all their clothing except their drawers and oiled their

bodies before they entangled in a wrestling match. These matches were

particularly popular after important processions and during various festivals.

Another nonmilitary sport was the game of

matrak,

in

which balls were struck with wooden clubs/sticks that were covered with leather

and looked like bowling ten-pins. The tops of the clubs were rounded and

slightly wider than the body. The game was a kind of battle animation, and it

was considered a lawn game. Throwing heavy stones or boulders was another

popular sport that survived until the end of the empire. The sport involved

throwing in a pushing motion a heavy stone or rock as far as possible. The game

was alluded to in various Greek folk songs, “which recounted the exploits of

brigand bands.”

Among the more sedentary and less physically demanding

games that remained popular throughout the history of the Ottoman Empire were

chess, backgammon, checkers (draughts), and cards. All these games were popular

among men who spent much of their time in coffeehouses. With the increasing

Westernization of the empire in the 19th century, a host of new and competing

European sports such as soccer (football), tennis, rugby, cycling, swimming,

gymnastics, croquet, boxing, and cricket were introduced. In Izmir in 1890, a

soccer and rugby club was organized, and in the winter of 1908–1909, an Ottoman

army officer, who had studied the impact of sports on the youth, embarked on a

campaign to educate the urban population on the benefits of physical exercise.

He organized several modern sport clubs. In Izmir, an athletic club began to

hold Pannonian Games, which included aquatic sports as well as soccer, cricket,

tennis, and fencing. Horseracing and hunting clubs also appealed to the Ottoman

love for traditional sports, and they sprang up in Istanbul where race courses,

mimicking those of France and England, were built by the government. Among the

imported sports to catch on, soccer was the most successful, while games such

as tennis remained confined to the four walls of the imperial palace.

Wrestling match, 19th century.

Anonymous.

13 - SICKNESS, DEATH, AND DYING

Death

was a common occurrence throughout the Ottoman Empire. As in other

pre-industrial societies, most deaths in the cities, towns, and villages of the

Ottoman Empire “were deaths of children.” Children “were particularly

susceptible to the intestinal diseases, such as dysentery and giardia,” and the

“most common killers of young children, from birth to age five, were diseases

of the intestines and the pulmonary system.” “Measles and smallpox” were also “common

causes of death among children.” Among the young adults living in the urban

centers of the empire, “the most common cause of death” was tuberculosis. According

to one source, “one-third to one-half of the recorded deaths of young adults in

Istanbul at the end of the 19th century were from tuberculosis and its

complications.” Typhoid also “killed as many as did smallpox, approximately 5

per cent of the young adult deaths were caused by each.”

In the rural regions of the empire, the principal causes of

death were malnutrition and lack of access to clean water. A population whose

diet was “primarily made up of carbohydrates, with few vegetables, fewer

fruits, and limited protein, were naturally susceptible to disease.” Water was

the principal carrier of many diseases, and “ignorance of the nature of the

disease was in itself” one of the most important “causes of death.”

Plagues frequently killed thousands of people in a short

span of time. Until the second half of the 19th century, plague was endemic and

virulent in Istanbul and other urban centers of the empire. Called “

veba

in

Turkish, the Arabic

waba,

‘to be contaminated,’ the lethal illness known

simply as ‘plague’ usually” referred to “bubonic plague, also known in the West

as the Black Plague or the Black Death.” Pandemic “throughout the empire from

the beginning of the 16th century to the middle of the 19th century, plague was

caused by the bacillus

Yersinia pestis

and was usually transmitted by

means of rodents infested with infected fleas.” Although “the disease was

endemic, meaning that it was both geographically widespread and constantly

present at some level in the population, periodic epidemic outbreaks of great

virulence frequently resulted in a 75 percent mortality rate among those

affected.” For “this reason, plague was greatly feared by Ottoman subjects and

by the foreign travelers who frequented the empire.” The disease “spread along

trade routes and the paths of pilgrims to and from Mecca.” As the majority of

pilgrims came from Anatolia and the Arab provinces, regions such as “Western

Anatolia, Egypt, and northern Syria reported plague epidemics most often.” When

a plague struck, people fled from the cities and towns to the countryside.

In “its most serious outbreaks, the plague disrupted the

Ottoman economy by interrupting harvests in the countryside and commercial

activities and handicrafts in the cities.” In many urban communities a

plague-stricken person was shunned and abandoned. In the southern Albanian town

of Gjirokastër, when a person developed a pimple or a boil, people immediately

concluded that he had the plague and fled from him. He was also prohibited from

entering homes. For two years afterward, people avoided entering the home of a

person who had suffered from the plague. Even after two years, they insisted on

cleansing the house with vinegar and disinfecting it with aromatic herbs. At

times, people went as far as tearing down and rebuilding various parts of the

house and whitewashing “all the rooms with lime before entering.” Without “any

modern understanding of germ theory, Ottoman doctors, like those in the West,

hypothesized that plague was an airborne infection caused by miasmas

(unpleasant or unhealthy air), carried by the wind.” An “alternative theory

attributed the spread of plague to demons, or jinni.”

Hardly less terrible “were the variations of cholera,”

which “once introduced spread with terrible rapidity.” The great 19th-century “cholera

epidemics struck the Middle East and Balkans with ferocity, each epidemic

killing hundreds of thousands.” Cholera spread primarily through Muslim

pilgrims from India who brought the disease to Mecca where pilgrims from the

Ottoman Empire contracted the disease. From Mecca, the pilgrims who had come

from all parts of Anatolia, Syria, Egypt, and so forth, brought the disease

home. Not surprisingly, Anatolia was devastated by the great cholera epidemics

of 1847 and 1865.

Another devastating epidemic that generally struck the

Ottoman Empire in times of wars and mass migrations was typhus. In the second

half of the 19th century, particularly from 1864 to 1880, Muslim refugees from

Russian conquests in the Balkans and the Caucasus died in large numbers from

typhus, which they spread in those regions of Anatolia and Syria where they

settled.

Borrowing from the practices of European states, during the

reign of Abdülhamid II, the Ottoman government introduced major improvements in

the area of public health. An international sanitary board was established and

quickly organized a quarantine system to prevent the entry of epidemic

diseases. Filth and garbage, as well as stray dogs, were removed from the

streets of the capital. The main streets of Istanbul and other urban centers

were paved “with basalt blocks,” which allowed rain water to wash them and “lessen

the accumulations of filth.” A well-organized medical school was established in

the capital to train students in medicine and modern sciences.

TRADITIONAL REMEDIES

Until the introduction of modern medicine, the people of

the Ottoman Empire relied on traditional remedies that had been passed down

from one generation to the next. In the 17th century, to cleanse their bodies

or as a remedy for various ailments such as yellow and black bile, phlegm, and

parasites, the people of Vlorë (Vlora), a major seaport and commercial center

in southwestern Albania, poured boiling pitch into a new cup, then rinsed it

thoroughly and drank water from the cleaned cup. Throughout the empire, popular

belief held that certain foods alleviated certain ailments and assisted with

certain deficiencies. For instance, according to popular belief, the eels of

Ohrid, the deepest lake in the Balkans, if caught fresh and wrapped in leaves

and roasted, not only made “a very nutritious meal” but also helped a man “have

intercourse with his wife five or six times” a day. Anyone “with consumption” [pulmonary

tuberculosis] who put “a salted eel head on his own head” was said to be cured “of

his ailments.”

At the Egyptian or Spice Bazaar (Misir Çarşi) in

Istanbul, gunpowder was prescribed as a remedy for hemorrhoids, and patients

were told to boil it with the juice of a whole lemon, strain off the liquid,

dry the powder and swallow it the next morning with a little water on an empty

stomach. Gunpowder was also “supposed to be a good cure for pimples when mixed

with a little crushed garlic.” Whatever its value as a pharmaceutical remedy,

gunpowder “was finally banned from the market because the shops in which it was

sold kept blowing up.”

The Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi writing in the 17th

century, reported that there were 2,000 men producing “ointments, pills, and

tinctures” and “selling around 3,000 different medicinal herbs and spices” in

and around the Egyptian Bazaar. Healers and men of medicine “made effective

pills from ambergris, a secretion from the alimentary tract of the sperm whale,”

which was believed “to strengthen the nerves and stimulate the senses.” Thus,

the spices, herbs, scented oils, and remedies sold in the form of paste, cream,

and syrup or powder traded in the Egyptian Bazaar were used not only to flavor

Ottoman foods and dishes but also as remedies for a wide variety of

deficiencies and ailments. From the sultans and members of the ruling family to

the humblest subject of the state, everyone relied on potions, thick syrups,

herbs, and spices as miracle cures.

In 1520, when Ayşe Hafsa Sultan, the mother of

Süleyman the Magnificent, became ill, the sultan sent a letter to a well-known

physician and healer who lived and worked at a mosque in the town of Manisa

(Magnesia) in western Anatolia, pleading with him to offer a cure for his

ailing mother who had fallen ill after mourning the loss of her husband, the

deceased sultan Selim I. Mixing 41 herbs and spices, the physician “concocted a

thick syrup” that saved the sick and dying widow. The queen mother expressed

her gratitude for this miracle by ordering that the syrup responsible for her

cure be distributed once a year among the people, a tradition that has

persisted to the present day. Every year, during the so-called Mesir Festival,

Mesir Paste (

Mesir Macunu)

is thrown to the crowds who gather in the

grounds of a mosque at Manisa named after the queen mother Ayşe Hafsa

Sultan. Also known as Turkish Viagra or Sultan’s Aphrodisiac, Mesir Paste,

which is a spiced paste in the form of a candy, is believed to restore health,

youth, and potency.

Ottomans also relied on prayers, charms, and spells as

potential cures, especially after the remedies of a physician failed to produce

positive results. At times, suras from the Quran were recited with gentle

breaths over the face and limbs of the ailing patient. Spells read in Arabic

and Persian were also considered effective, provided certain conditions were

met. Unfortunately, such prerequisites could create embarrassing situations.

Reciting a spell to an ailing and dying high government official, Evliya Çelebi

complained that the efficacy of his spell required the reciter to “strike the

palsied man’s face three times with his own shoe, holding it in the left hand.”

The ailing man in this particular instance, however, was a grand vizier, and

Evliya could not strike him with a shoe.

Some holy men used their breath to treat physical, mental,

or nervous disorders. The patient was placed in front of the healer, who went “into

a kind of trance, at intervals blowing in the direction” of the patient who was

being treated. The breath, “thought of as the essence of one’s self, was

believed to carry healing virtue to the patient.” Rich and poor, young and old,

women and men were convinced that when doctors failed to cure a patient, puffs

of breath from holy men could remedy their illness.