Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (11 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

Several times a week, at fixed times, the ministers met to

listen to complaints from the subjects of the sultan. The council comprised of

the grand vizier, who acted as the personal representative of the sultan, and

his cabinet, known as the viziers of the dome, because they met in the domed

chamber of the Topkapi Palace. Those attending included the chief of

chancellery, or lord privy seal (

nişanci)

, who controlled the

tuğra

(the official seal of the Ottoman state) and drew up and certified all

official letters and decrees; the chiefs of the Islamic judicial system (

kadiaskers)

who represented the religious establishment or the ulema and assisted the

sultan and the grand vizier in legal matters; and the treasurers (

defterdars

)

of Anatolia and Rumelia (Ottoman provinces in the Balkans), who oversaw the

royal revenues originating from Rumelia, Anatolia, Istanbul, and the

northwestern coast of the Black Sea. The

defterdars

communicated to the

grand vizier the daily transactions of the central treasury and had to ensure

that the troops stationed in the capital received their pay in a timely

fashion.

Prominent military commanders also attended the council.

Beginning in the 16th century the

ağa,

or commander of the sultan’s

elite infantry, the janissaries, took part in the council’s meetings. The

commander of the

sipahis

also attended. The members of this cavalry

corps received revenue from

timars

or fiefs held by them in return for

military service. Süleyman I, who recognized the increasing importance of the

imperial navy, appointed Grand Admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa to the council. Although

the chief admiral of the Ottoman fleet (

kapudan paşa)

attended the

meetings of the imperial council, he reported directly to the sultan on the

readiness of the imperial arsenal and the Ottoman naval forces. The grand

vizier and his cabinet were accompanied by the

çavuş başi

(the

head

çavuş

), the chief of the palace officers who maintained order

and protocol at imperial council meetings and palace ceremonies, and who were

dispatched as couriers to convey messages and execute orders. Clerks and

scribes, numbering some 110 in the 1530s, worked under the supervision of the

reisülkütab

or chief of scribes, who acted as the head of the offices attached to the

grand vizier. Each Ottoman high official maintained a large household, a kind

of imperial palace in miniature, as a manifestation of his prestige and power. His

retinue “consisted of several hundred officers, ranging from menial domestics

and bodyguards to companions and agents.”

At the time of Mehmed II, the imperial divan “met every day

of the week, but in ensuing years this changed and the council met four times a

week” on Saturdays, Sundays, Mondays, and Tuesdays. The viziers who served in

the divan arrived on horseback with pomp and ceremony. They were surrounded by

their retinues, including their sword bearer, valet, and seal bearer, and dressed

“in solemn dress, according to the offices they held.” The grand vizier arrived

last riding alone at the end of an imposing cavalcade. Until the reign of

Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, the sultan participated in the

deliberations of his ministers. As the power and the territory of the empire

grew, the sultan became increasingly detached and stopped participating in the

meetings of the divan. Instead, a square window especially cut to overlook the

council chamber allowed the sultan to listen in on the deliberations of his

ministers whenever he chose.

As the viziers entered the divan, they sat in accordance

with their position and status on a low sofa, which was attached to the wall

and faced the main door to the audience hall. The

kadiaskers

of Rumelia

and Anatolia sat to the left of the grand vizier, while the

defterdars

of

Anatolia and Rumelia sat to his right. The scribes sat behind the treasurers on

mats, which were spread on the floor. Next to the treasurers sat the

nişanci

with a pen in his hand, accompanied by his assistants. The

reisülkütab

stood

close to the grand vizier who frequently requested his opinion and services.

As an executive body, the imperial council conducted all

manner of government business. It addressed foreign affairs, granted audiences

to ambassadors, and corresponded with foreign monarchs. It oversaw the empire’s

war efforts by issuing detailed commands regarding the use of manpower,

munitions, and provisions. It also supervised the building of public works, notably

fortresses and aqueducts in Istanbul and the provinces. In addition, the

council dealt with any number of problems brought to its attention through the

reports and petitions of governors and judges. Finally, the council both

appointed and promoted government officials.

The council also acted as a court of law, hearing cases

that involved the members of the ruling class as well as complaints from

ordinary folks. As one European observer wrote: “The Pashas” heard first the

most important cases, “and then all the others, of the poor as well as of the

rich,” so that no one departed “without being heard or having” his case

settled. Once all the viziers had been seated, the petitioners were allowed to

enter the divan and present their case or complaint. There were no attorneys or

representatives present, and the authority to make the final judgment on each

and every case rested solely with the grand vizier. He was the only government

official who spoke during the proceedings unless he sought the opinion of one of

his viziers.

The deliberations at the divan continued for seven to eight

hours. The members of the imperial council ate three times. First, “at dawn,

immediately after their arrival, then ‘at the sixth hour,’ after the main

business, and then after hearing petitions.” At noon, the grand vizier asked

attendants to serve lunch. Ordinary people who were present at the time were

asked to leave so that the cabinet could enjoy their meal free of crowds and

noise. Large round copper trays set on four short-leg stools were placed in

front of the grand vizier and other members of the divan. The grand vizier

shared his food tray with two other officials. Other viziers followed the same

pattern. They sat with a colleague or two around the large copper tray, and

they shared the meal served by the palace kitchen.

Before they started their meal, all government officials

spread a napkin on their knees to keep their garments clean. Then the servers

placed freshly baked bread on the trays, followed by dishes of meat. As the

viziers tasted from one plate, the servers brought a new dish and removed the

plate that had already been tried. The grand vizier and his cabinet dined on

mutton, “hens, pigeons, geese, lamb, chickens, broth of rice, and pulse” cooked

and covered with a variety of sauces. The leftovers were sent to the retinues

of the ministers and dignitaries although they also had their food brought from

their own palace kitchen. Unlike the sumptuous meal served to high government

officials, however, their lunch was bread and pottage, which was called

çurba.

For drink, sherbets of all kind, as well as water, were served in porcelain

dishes.

Meetings “ended in midday in the summer, when daybreak was

early, and mid-afternoon in winter.” On Sundays and Tuesdays, the grand vizier

met with the sultan after the meeting at the divan had ended. At times, other

ministers were called to the sultan’s audience chamber to provide reports.

Aside from the grand vizier, the chief treasurer was the only minister who

could speak directly to the sultan, while the other members of the divan merely

stood silently with their hands crossed on their chests and their heads bowed

as a show of their reverence and obedience. Having listened to these reports

and deliberations, the sultan dismissed the members of the divan and the grand

vizier, who departed the palace accompanied by a large escort of palace

officials. The last to leave the palace was the commander of the janissary

corps. On days when they did not meet with the sultan, the imperial council

left as soon as their meeting at the divan had concluded.

According to a European diplomat who visited the Ottoman

court in the 17th century, the sultan gave audience to foreign dignitaries on

Sundays and Tuesdays. There were several specific occasions when the sultan or

the grand vizier received foreign envoys. The most common of these was when an

envoy arrived at the palace to present his credentials upon first assuming his

post or after he had been promoted. Another occasion was the arrival of a foreign

envoy who was sent by his government to congratulate the enthronement of a new

sultan. The decision about whether the envoy was received by the grand vizier

or the sultan depended on the status of the envoy, the ruler and the state he

represented, and “the nature and quantity of the gifts” he intended to present.

If the foreign envoy “was received by both the sultan and the grand vizier, the

audiences took place on different days.”

When the sultan agreed to meet with a foreign envoy, the

grand vizier dispatched government officials and a group of elite horsemen

attached to the palace, comprised of the sons of vassal princes and high

government officials, to accompany the ambassador and his men to the royal

residence. Once he had arrived at the palace, the ambassador was seated across

from the grand vizier on “a stool covered with cloth of gold.” After the

exchange of customary niceties and formalities, lunch was served with the grand

vizier, the ambassador, and one or two court dignitaries, sharing a large,

round copper tray covered with a variety of delicately cooked dishes. Coffee

and sweetmeats followed the sumptuous meal.

After lunch, the ambassador and his attendants were

escorted to a place close to the imperial gate where they waited for the

arrival of the chief eunuch, who acted as the master of ceremony. Once he had

arrived in the sultan’s audience hall, two designated high officials took the

ambassador by either arm and led him to kiss his majesty’s hand, which in

reality was a sash hanging from his sleeve. The same two court officials led

the ambassador back to his place at the end of the room, where he stood and

watched as the members of his delegation went through the same exact ceremony

of being led to the sultan to kiss the royal sleeve. Early Ottoman sultans rose

from their seats to recognize envoys who entered the imperial presence. As the

Ottoman military power reached its zenith in the 16th century, however, Ottoman

sultans, such as Süleyman the Magnificent, neither rose to their feet nor

allowed envoys sit in their presence. As late as the 18th century, the sultan

continued to be seated, but starting with the reign of Mahmud II (1808–1839),

Ottoman monarchs adopted “a more courteous attitude” toward foreign envoys,

standing up to greet them. Once the ceremony had finished, the dragoman, or the

interpreter, announced the ambassador’s diplomatic commission, to which the

sultan did not reply because such matters were left to the discretion of the

grand vizier.

Until “the 19th-century reforms, the Ottoman government,

unlike the governments of modern nation states, was small,” and “its tasks were

limited to a few key areas: defense of the empire, maintenance of law and

order, resource mobilization, and management and supply of the capital and the

army.” Other important concerns familiar to the governments of modern states

such as education, health care, and common welfare were the purview of the

empire’s religious communities and professional organizations such as pious

foundations and guilds.

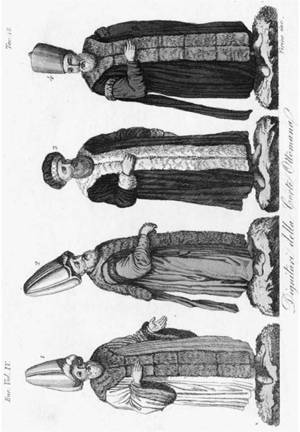

Dignitari della corte Ottomana

(Dignitaries of the Ottoman Court).

62 Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire

DEVŞIRME

Those who managed the empire as governors, provincial

administrators, and army commanders, received their education and training in

the royal palace. They had been recruited as young slaves and brought to the

palace, where they were trained as the obedient servants of the sultan. The

Ottomans did not recruit these slaves from the native Muslim population.

Rather, young Christian boys from the sultan’s European provinces provided him

with a vast pool from which new slaves could be recruited, converted to Islam,

and trained to assume the highest posts in the empire. Known as the

devşirme

(collection), this system also resulted in the creation of the

yeni çeri

(new soldier) or janissary corps, who constituted the sultan’s elite

infantry and were paid directly from the central government’s treasury.