Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (6 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

The Ottoman constitution did not prevent another military

confrontation with Russia. Continuous palace intrigues convinced Abdülhamid II

to dismiss Midhat Paşa, who was sent into exile in February 1877, an event

that was soon followed by a Russian declaration of war in April. The Ottoman

forces delayed the Russian southward incursion for several months at Plevna

(Pleven) in Bulgaria, but by December, the tsarist army was encamped a mere 12

kilometers outside Istanbul. On 3 March 1878, the Treaty of San Stefano was

signed between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Among other things, it called for

the establishment of an autonomous Bulgarian state, stretching from the Black

Sea to the Aegean, which Russia would occupy for two years. Serbia, Romania,

and Montenegro were also to be recognized as independent states, while Russia

received Batumi in southern Caucasus, as well as the districts of Kars and

Ardahan in eastern Anatolia. Additionally, the Ottoman government was obliged

to introduce fundamental reforms in Thessaly and Armenia. Other European powers

could not tolerate the rapid growth of Russian influence in the Balkans and the

Caucasus. They agreed to meet in Berlin at a new peace conference designed to

partition the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire in such a way as to

prevent the emergence of Russia as the dominant power in the region.

DISINTEGRATION OF THE EMPIRE IN THE

BALKANS

The Congress of Berlin, which began in June 1878, was a

turning point in the history of the Ottoman Empire and southeast Europe. When

the congress ended a month later, the Ottoman Empire was no longer a political

and military power in the Balkans. The Ottomans lost eight percent of their

territory and four and a half million of their population. The majority of

those who left the empire were Christians, while tens of thousands of Muslim

refugees from the Balkans and the Caucasus fled into the interior of the

empire. The large Bulgarian state that had been created three months earlier at

the Treaty of San Stefano was divided into three separate entities. The region

north of the Balkan Mountains and the area around Sofia were combined into a

new autonomous Bulgarian principality that would recognize the suzerainty of

the sultan, but for all practical purposes act as a Russian satellite. The

region lying between the Rhodope and Balkan mountains, which corresponded with

Eastern Rumelia, was established as a semiautonomous region under its own

Christian governor, who was to be appointed by the sultan and supervised by

European powers. The third area of Thrace and Macedonia remained under Ottoman

rule.

The Berlin Congress did not provide Greece with any new

territory. Instead, the powers asked that Greece and the Ottoman Empire enter

into negotiations on establishing the future of their boundaries, including the

status of Thessaly and Epirus. Austria was granted the right to occupy and

administer Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as the

sancak

of Novi Pazar, a

strip of land that separated Serbia from Montenegro. Further, while the

Congress recognized Serbia, Romania, and Montenegro as independent states, the

Romanian state was forced to hand southern Bessarabia to Russia and, in return,

receive Dobrudja and the Danube Delta. Russia also received the districts of

Batumi, Kars, and Ardahan, thereby establishing military control over the

eastern shores of the Black Sea and a strategically important land bridge to

Anatolia.

The British received the island of Cyprus, which contained

a Greek majority and a Turkish minority population. By handing

Albanian-populated areas and towns to Montenegro and Greece, the European

powers ignited a new nationalist movement among a proud people who had

faithfully served the Ottoman state on many occasions in the past. Thus,

Albania, with its emerging national movement, would replicate the model set by

the Serbs, the Romanians, and the Bulgarians and demand independence.

Although Serbia, Montenegro, Romania, and Bulgaria gained

their independence or autonomy in 1878, the Congress of Berlin left the newly

independent states dissatisfied and hungry for more territory. The Romanians

were angry because they were forced to cede the rich and productive Bessarabia

in return for gaining the poor and less productive Dobrudja. The Bulgarians were

outraged because they lost the greater Bulgarian state, which had been created

by the Treaty of San Stefano. Serbia gained limited territory, but it did not

satisfy the voracious appetite of Serbian nationalists who dreamed of a greater

Serbia with access to the sea. Montenegro received a port on the Adriatic, but,

as in the case of Serbia, it did not acquire the towns and the districts it had

demanded. Of all the participants in the Congress, Russia was perhaps the most

frustrated. In return for its massive human and financial investment in the war

against the Ottoman Empire, it had received only southern Bessarabia in the

Balkans, while the Austrians, who had opportunistically sat on the sidelines,

had been awarded Bosnia-Herzegovina.

These frustrated dreams turned the Balkan Peninsula into a

ticking bomb. By carving the Ottoman Empire into small and hungry independent

states, the European powers laid the foundation for intense rivalries.

Thirty-six years after the conclusion of the Berlin Congress, the Balkan

tinderbox exploded on 28 June 1914, when Serbian nationalists assassinated the

Austrian crown prince, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo, sparking the

First World War.

ABDÜLHAMID II

With the removal of Midhat Paşa in 1877, the center of

power began to shift back from the office of the grand vizier to the sultan.

Despite the defeat at the hands of the Russians and the territorial losses

imposed by the Congress of Berlin, the new sultan, Abdülhamid II (1876–1909), remained

committed to the reforms introduced during the Tanzimat period. Indeed, it was

during his reign that a new and Western-educated officer corps emerged.

Ironically, the same officers would play an important role in deposing the

sultan in April 1909. In addition to emphasizing military training, the sultan

expanded elementary and secondary education (including the opening of a new

school for girls in 1884), introduced a modern medical school, and established

the University of Istanbul. To create a modern communication system for the

empire, he developed telegraph services and the Ottoman railway system,

connecting Istanbul to the heartland of the Arab world as far south as the holy

city of Medina in Hejaz. The Hejaz railroad, which was completed in July 1908,

allowed the sultan to dispatch his troops to the Arab provinces in case of a

rebellion.

As with the reforms introduced by the men of Tanzimat, the

principal objective of Abdülhamid II’s modernization schemes was to establish a

strong and centralized government capable of maintaining the territorial

integrity of the empire. In practical terms, this meant suppressing uprisings

among the sultan’s subjects and defending the state against the expansionist

policies of European powers. Despite the sultan’s best efforts, however, the

empire continued to lose territory.

Building on their occupation of Algeria in 1830, the French

imposed their rule on Tunisia in May 1881. A year later, the British invaded

and occupied Egypt. In addition to these losses, the Ottoman Empire also

continued to lose territory in the Balkans. After the Congress of Berlin, the

only area left under Ottoman rule was a relatively narrow corridor south of the

Balkan Mountains that stretched from the Black Sea in the east to the Adriatic

in the west, incorporating Thrace, Thessaly, Macedonia, and Albania. Greece,

Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria coveted the remaining territory of the dying

Ottoman Empire. In accordance with the promises made at the Congress of Berlin,

the Ottomans handed much of Thessaly and a district in Epirus to Greece in July

1881. Despite these gains, Greece continued to push for additional territorial

concessions including the island of Crete, where several uprisings, encouraged

by Athens, forced the sultan in 1898 to agree to the creation of an autonomous

Cretan state under Ottoman suzerainty. The island finally became part of Greece

in December 1913.

Aside from the military disasters and territorial losses

that the empire suffered, the reign of Abdülhamid II proved to be a period of

significant social, economic, and cultural transformation. The autocratic

sultan continued with the reforms that had been introduced by the men of

Tanzimat. There was, however, a fundamental difference. The statesmen of the

Tanzimat had begun their governmental careers as translators and diplomats

attached to Ottoman embassies in Europe, and thus wished to emulate European

customs and institutions. Abdülhamid II, in contrast, may have been a

modernizer, but one who believed strongly in preserving the Islamic identity of

the Ottoman state. With the loss of its European provinces, the number of

Christian subjects of the sultan decreased and Muslims began to emerge as the

empire’s majority population. The Muslim population was not only loyal to the

sultan but also felt a deep anger toward the sultan’s Christian subjects for

allying themselves with the imperial powers of Europe in order to gain their

independence. Abdülhamid II understood the new mood among his Muslim subjects

and countered European imperial designs by appealing to Pan-Islamism, or the

unity of all Muslims, under his leadership as the caliph, or the religious and

spiritual leader of the Islamic world.

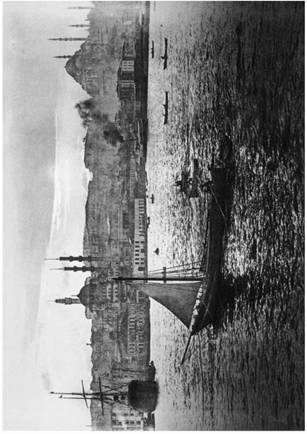

A view of Istanbul between 1880

and 1890.

YOUNG TURKS SEIZE POWER

Despite Abdülhamid II’s best efforts to preserve the

territorial integrity of the empire and to modernize the Ottoman society, the

government failed to neutralize the opposition of the young, educated, and

secular minded elements in the society. As early as 1889, small groups of

patriotic students, civil servants, and army officers had organized secret

societies. Princes of the royal family, government officials, teachers,

artists, and army officers educated and trained in modern schools and military

academies, had concluded that the restoration of the 1876 constitution and the

establishment of a new government based on a parliament were the only means

through which the Ottoman Empire could be saved from further disintegration. As

the police began to crack down on the opposition, some chose exile over

imprisonment and settled in European capitals, where they published newspapers

that denounced the autocratic policies of the sultan. Others recruited young

cadets and organized secret cells among army units stationed in the Balkans and

the Middle East. This diverse group of antigovernment Ottoman intellectuals and

activists, who were known in Europe as

Jeunes Turcs,

or the Young Turks,

organized themselves as the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).

Revolution came, unexpectedly, from Macedonia in July 1908,

when army officers loyal to CUP revolted and demanded the restoration of the

1876 constitution. After a faint effort to suppress the rebellion, Abdülhamid

II concluded that resistance was futile. On 23 July, he restored constitutional

rule and ordered parliamentary elections throughout the empire. As the news of

the revolution spread, massive celebrations erupted, particularly in Istanbul,

where Turks, Jews, Armenians, and Arabs joined hands and embraced in the streets

of the capital. Among the deputies to the new parliament, which opened on 17

December, there were 142 Turks, 60 Arabs, 25 Albanians, 23 Greeks, 12

Armenians, 5 Jews, 4 Bulgarians, 3 Serbs, and 1 Romanian.

The Young Turks had convinced themselves that the

restoration of the parliamentary system of government would secure the support

of European powers for the preservation of the territorial integrity of the

Ottoman Empire. They were mistaken. Shortly after the victory of the

revolution, the Austro-Hungarian Empire formally annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina,

while Greece seized the island of Crete, and Bulgaria unified with Eastern

Rumelia, which had remained an autonomous province under the nominal rule of

the Ottoman sultan.

Meanwhile, an attempted counter coup by supporters of

Abdülhamid II in April 1909 provided an excuse for the two chambers of

parliament to depose the sultan and replace him with his younger brother, who

ascended the throne as Mehmed V (1909–1918). The center of power had shifted

once again, this time from the palace to the army, the bureaucracy, and the

parliament. The central government, however, continued to be plagued by

internal factionalism and growing opposition from both conservative and liberal

groups and parties. The weakness of the government was demonstrated by its

failure to respond effectively to the unrest in Albania, the uprising of Imam

Yahya in Yemen, and the Italian invasion of Tripoli and Benghazi in Libya. The

Italian attack on the Dardanelles and the occupation of the Dodecanese Islands

in May 1912 forced the Ottoman government to accept the loss of Libya and sue

for peace.