Crossing the Borders of Time (70 page)

When morning came, I called my cousins in Mulhouse and asked if I might spend the weekend with them. It was a side trip I had not at all anticipated. But my airplane home was three days off, and like my grandparents in 1938, I decided that if I couldn’t get to America immediately, the time had come to leave for France. Michael kindly volunteered to drive me there, and as we crawled to a stop at the checkpoint at the river—the long-disputed border that once divided the hope of life from almost certain death—I was shocked to see the guards just glance at us perfunctorily and wave us through.

Indeed, the watch on the Rhine spotted nothing worth investigating in the car that carried me on the path of my family from Poststrasse 6 in Freiburg to relatives in Mulhouse. Nothing unusual in our traveling together, German and Jew whose histories unfolded from the very same address. I myself was only starting to perceive the import of my journey—that the force and nearness of the past were luring me to France on a mission of salvation.

The lesson I’d learned in Germany was that the past was not a thing forever lost, but rather a place that was waiting to be found. Faces lined by years were waiting to be recognized. Yes, crossing the Rhine, I was following a route that my mother had mapped out and shared with me for decades, as if preparing me to meet the challenge of this moment. Now I would go to find Roland, as my mother had before me.

TWENTY-FIVE

THE AGENDA

T

HERE WERE THREE

Arcieris listed in the Mulhouse telephone directory—one woman and two men—but to my disappointment, no one named Roland. Had I really let myself imagine that finding him would be so easy? The fact that my cousin Michel Cahen was still living in the same house where decades earlier

my

parents had visited

his

parents, Edy and Lisette, tempted me to hope that families in Alsace tended to stay rooted.

My cousins’ house was located in the same residential section high above the city where I remembered Mother saying the Arcieris lived before the war. So as I drove with Michael Stock through the green and well-kept neighborhood, searching for the Cahens’ address, the fantastic possibility began to blossom in my thinking that I might actually meet Roland that very afternoon. Living on the Rebberg, too, it seemed quite likely that my cousins knew him. Lisette, who had met him with my mother in the war, would certainly have introduced them—neighbors, after all.

But once among my cousins, I shrank from telling Michel and his wife, Huguette, and his sister Isabelle, just arrived from Paris for the weekend, the reason for my fervent interest in tracking down a Frenchman who was a stranger to me. Except for Isabelle, I didn’t know my Mulhouse cousins very well and worried what they’d make of it. In recent years, moreover, Michel had startled all the family by embracing such strict new piety that within the very hour of our landing on his doorstep, he was rushing off to synagogue for closing Sabbath prayers with Isabelle and me in tow, there to be consigned to the women’s section in the balcony. Thus it seemed unlikely he’d condone my seeking out my mother’s former lover, a Catholic who was probably long married. With my father’s days so numbered, how awful it would be if Michel wrongfully assumed that Mom herself had dispatched me on this quest, coolly looking forward to a future on her own. He was bound in any event to regard it as delusional for me to nourish hopes of bringing back a love long buried in Mom’s past.

At dinner I aimed to strike a casual tone: I took a gulp and plunged ahead and asked about Roland. Michel was silent for a moment, then said, yes, he thought that Edy had represented Roland Arcieri’s wife in a divorce. I tried to smother my delight—divorce!—and bit my lips to keep from betraying Schadenfreude. But my interest must have been transparent. That divorce was very long ago, Michel said, studying my face as he glanced up from his salad. He didn’t have a clue, he added pointedly, whether either party had remarried.

“His former wife still lives in Mulhouse,

là, j’en suis sûr

,” he said. “Her family has a prominent flower business. But I don’t know about Roland.” He paused as if debating how much to reveal, told his son to pass the bread, then added that he knew a woman lawyer, once a protégée of Edy’s, whose maiden name had been Arcieri. Perhaps she was related to the man I hoped to find? (In an intersecting network of small-town relations, it turned out she was the daughter of Roland’s first cousin, André; I would also learn that Mom’s onetime classmate, Yvette, who introduced her to Roland in 1938, much later on became Isabelle’s high school English teacher and a friend of the Cahen family.)

After dinner—Michel adding to my self-consciousness by settling in an armchair to read the newspaper in easy earshot of the telephone—I called the colleague he suspected might be related to Roland. But when I failed to get an answer, I was left with no alternative on my only night in town but to try all three Arcieris listed in the phone book. I dialed with no clear thought of what I’d say if anyone responded. Intentionally, though, I started with the men, feeling that before I called the woman I would have to brace myself to learn that Roland had ultimately remarried and subsequently died, leaving her his widow. But neither man replied, and when I called the woman, Emilienne Arcieri rewarded me by saying she was Roland’s

sister

! Stammering for words, I said I hoped to reach him because my mother, known as Janine Günzburger before her marriage, had been Roland’s friend in Lyon in the 1940s. But if I hoped my mother’s name would evoke a more cordial note of recognition, Roland’s sister said she’d never met Janine and did not remember anything about her. Besides, she added brusquely, Roland no longer lived in town. Or in France, for that matter. Just when I thought she would hang up, however, she asked me to hold on for a moment. When she came back to the telephone, she surprised me by insisting that she’d prefer to speak in person, so I should come to see her.

The following morning I consequently found myself standing frozen with a drumming heart before the entrance of an apartment building where Isabelle deposited me on the avenue Robert Schuman in the lower city. No meeting of my life seemed as magically momentous as the one that I was facing. As I lingered in the empty lobby in the milky light of daytime behind frosted plate-glass windows, I felt fearful of resolving lifelong questions with answers that could lead to permanent unhappiness.

Slowly, debating my best approach with her, I made my way upstairs, rang the bell, and heard her footsteps echo on a hardwood floor. When the door swung open, I stared with disbelief into a face that imagination had imbued with all the perfect features I had admired since childhood in Mother’s few remaining photographs of Roland. But Emilienne Arcieri was altogether different from her younger brother. In sorry fact, beneath the glare of the hallway’s fluorescent light, she was alarming in her homeliness. The nose and mouth so harmonious on him lay heavy and masculine upon her wrinkled visage. Her thick brown brows drooped above her glasses and slanted toward her fleshy ears, which lent her the expression of a mournful basset hound. The rest was a study in challenging topography. Matching furrows were dug into her sallow cheeks, running southward from the midpeak of her alpine nose, and her jowls spread thick and soft. She stood erect in sturdy shoes with shoulders squared, armed against the autumn chill with a cardigan pulled across a belted shirtdress. Stretching to unexpected lengths below her elbows and her knees, her arms and legs were straight and bony, and she was taller than I had pictured. Her sole adornment was a simple golden crucifix that dangled from a chain about her neck.

We shook hands at the threshold, and inside Emilienne offered me a chair in a bright though sparsely furnished living room and then excused herself to prepare tea in the kitchen. When she returned, balancing a tray that provided us the buffering distraction of mutual activity, she perched upon a stool across a little table from me, giving the impression she might take flight at any moment. Conversation started cautiously. While I was awkward and ambiguous in defining why I’d come, presumably she also had a purpose—as yet unstated—for inviting me to meet her. Thus we poked around each other with guarded curiosity. I told her I had come to France after a few days’ trip to Germany to see my cousins on the Rebberg, and she told me she had lived near them until she’d moved downtown.

Her life story was a poignant one, gradually revealed with prompting, but without self-pity. Society, like nature, had been stingy in dispensing gifts to her, and marriage had never been an option. She’d purchased her apartment nearly thirty years before, when the building seemed a marvel in its newness and crisp modernity. She had saved to buy it, working as a secretary in the office of a local potash-mining firm. After retiring in the 1960s, she’d devoted all her energies to serving God and caring for her mother, who refused to leave the home where she had reared her family. Only when her mother died at the age of ninety-nine and Emilienne was nearly seventy could she finally permit herself to move into her “new” downtown apartment—decades old by then, in need of paint and waiting for her, empty. Even as we sat there, it struck me that the cold and boxy space was suggestive of a person who had either trimmed her world to bare essentials or else, almost like a cloistered nun, Emilienne Arcieri had never roamed or tasted life enough to garner any keepsakes of memorable experience. At least, that is, mementos of her own.

“I don’t get many visitors, but I’m very glad you’re here,” she said. At first I took her sentiment for standard hospitality. “Although I never knew your mother, I have something that belongs to her. I have always wanted to return it, but of course I had no idea of how to find her. This is why I asked you here.”

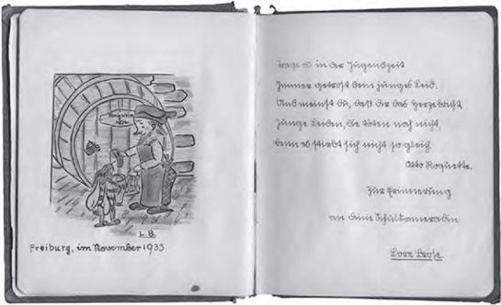

Suddenly she stood and strode across the room to a contemporary shelving unit of glass and chrome, where an image of the Holy Family, displayed within a modest frame, was one of several pictures in the room that seemed to have been salvaged from the pages of an illustrated Catholic calendar. On a higher shelf, from the middle of a row of books, she withdrew a little volume that she wordlessly placed into my hands. It was covered in red paper with a design of four-leaf clovers and bore a printed sticker glued onto the front:

Hanna Günzburger

Freiburg Br.

Poststraße 6

Tel. 2833

Inside the book, barely legible to me in that complicated German script called

Sütterlin

, Mom had also inked that same address, and beneath it, in more familiar penmanship, her address in Mulhouse. From cover to cover, the pages were filled with poems and messages dated from 1935 to 1938, most of them written by her friends in German as perplexing to decipher as her

Sütterlin

address. Still, I was astounded by the charming colored drawings that accompanied the entries. With exceptional artistry and whimsy, my mother’s girlhood friends had drawn or painted elves with beards and pointed caps, children in folkloric dress, animals and insects, flowers and gardens, illustrations of nursery rhymes, and early Disney cartoon characters. Silhouettes of dogs and cats and little girls and flowers were detailed cutouts from black paper that meticulously decorated several other pages.

The autograph book that Janine left behind with Roland in 1942 is a creative jewel, filled with delightful pictures and poems from her girlhood friends, including this entry by Lore Brose

.

My eyes welled up with grateful tears, and I couldn’t trust myself to speak. I was holding in my hands the treasure I remembered Mother saying she had given to Roland in pledge before she left Lyon as tangible proof that someday she would return to him. It was not a thing she would abandon. For me, as once for Mom and for Roland, this cherished book of friendly messages provided lasting testimony of the truth of their relationship. How astounding that this devout and austere woman, seemingly starved of love herself, had kept it at her fingertips after all these years. In the archaeology of love, this discovery was priceless, a tantalizing shard that impelled me to keep digging.