Cross and Scepter (9 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

The Law of 1163/64 may be regarded as an attempt to assure peaceful succession to the throne, but it was first and foremost intended to protect the ruling king, Magnus Erlingsson, against his rivals, by defining their claims as illegal and stamping them as rebels and heretics. Magnus was only seven years old and related to the dynasty through his mother, but he had the advantage from point of view of the Church that he was born in marriage. The real ruler during Magnus's minority, and even longer, was his father, the Earl Erling Ormsson, nick-named Skakke (the Wry-neck). However, far from protecting Magnus against rivals, the law occasioned a most intense period of internal conflicts. Magnus was challenged by a queue of rivals, the most important of whom was Sverre Sigurdsson, allegedly an illegitimate son of a previous

king. During a series of campaigns, Sverre managed to defeat and kill first Erling (1179) and then Magnus (1184), rule until his death in 1202, and leave the kingdom to his descendants, although he had to spend most of his reign fighting rebellions. His grandson HÃ¥kon HÃ¥konsson put an end to the internal struggles and consolidated the kingdom during his long reign (1217â1263). During his and his successors' reigns, the principle of individual succession by the king's eldest son was laid down in the Law of 1260, revised in 1274 and 1302. These laws were based exclusively on the principle of hereditary succession. They decreed that an assembly should meet after the death of a king, but that its duty was only to acclaim the next in the line of succession. An election would only take place in case the dynasty had become extinct.

The first king of Sweden of whom we have any concrete knowledge is Olof Skotkonung (“the Tax King,” so called either because he taxed his people or because he had to pay tribute to King Cnut the Great), who fought at Svolder. He issued coins, some of which are extant. Olof may have been recognized as king of most of present-day Sweden, but his main area seems to have been in the west. We know the names of his successors until the thirteenth century, but very few details about them. Medieval Sweden was divided into three main parts, from west to east: Västergötland, Ãstergötland, and Svealand. Lake Vättern forms the line of division between the two former, whereas Svealand is the fertile area around Lake Mälaren. From the late eleventh century onwards, there were almost continuous struggles over the throne between two dynasties, the one of Erik and the one of Sverkerâboth named after the most frequent names of their kings, most of whom were either murdered or killed in battle. The former dynasty had its main base in Västergötland, the latter in Ãstergötland, but both tried to control as much as possible of the country. No real unification of the country seems to have happened, however, until the mid-thirteenth century. The Sverker

dynasty became extinct in 1222, which left Erik Eriksson (1222â1250) on the throne. He was succeeded by his sister's son Valdemar, son of the mighty Earl Birger, who was the real ruler until his death (1266), as he had also been during the latter part of Erik's reign. Birger's descendants continued to rule Sweden until the second half of the fourteenth century. Primogeniture and individual succession were introduced here as well, but, at least in the beginning, with limited success. There was a strong tradition of elective kingship, and after the election, the king had to travel around in the country to receive popular acclamation in the various provinces (

Eriksgata

). The Code of the Realm of 1350 explicitly stated that kingship in Sweden was elective and not hereditary.

The regulation of the succession took place during periods of frequent struggles between pretenders to the throne, in Denmark between 1131 and 1170, in Norway from 1130 to 1240, and in Sweden more or less continuously until the mid-thirteenth century. Although to some extent a symptom of incomplete state formation, these struggles actually led to increased centralization. They were not struggles between the central power and magnates attempting to carve out independent territories; the contending parties all aimed at securing the central power for themselves. In contrast to some suggestions, particularly from Norwegian historians, there is also little to suggest a conflict between an emerging aristocracy and the rest of the population. Although there is clear evidence of a strong aristocracy in all three countries even before this time, the divisions are more likely to have been between various aristocratic factions than between social strata. Nor did the struggles usually transcend established borders. Admittedly, pretenders in one country often received aid from supporters in anotherâin particular, the king of Denmark often intervened in this way in the other countries and may indeed have had territorial gain as one of his aims. In the 1160s, he tried to annex

the Oslofjord area, but in the end had to confine himself to letting the earl Erling Skakke rule it on his behalf. In most cases, however, the pretenders and factions were specific to each country. The attempts to achieve final victory and secure it led to military and administrative reforms, which were continued by the victors of the struggles, Valdemar I and his successors from 1157 in Denmark, HÃ¥kon HÃ¥konsson and his successors from 1240 in Norway, and Earl Birger and his successors from 1250 in Sweden (as kings from 1266).

The formation of a dynasty, combined with rules about individual succession, gave the monarchy a legal foundation. One particular person had a birthright to rule the country, which was in this sense his property, in the same way as a farmer had the right to his land. This was most clearly set forth in Norway, where the monarchy was defined as hereditary and where this analogy actually occurs in the mid-thirteenth-century

King's Mirror

, but the principle of individual succession and thus of one individual's exclusive right to the realm was equally strong in the two other countries, where the monarchy was elective. The idea of lawful succession and the king's right to rule the country was developed in charters, historiography, and didactic works, and served to defend the monarchy against internal as well as external rivals. To this was added the ecclesiastical ideology of kingship as an office and the king as God's representative on earth, expressed in the ritual of coronation, introduced in Norway in 1163/64, in Denmark in 1170, and in Swedenâwhere it never had the same importance as in the other countriesâin 1210. During the coronation, the king received the symbols of his power: crown, scepter, globe, and sword, which served to distinguish him from other people and appeared in pictures, statues, and seals to represent the royal dignity. He also had a special seat, the throne, to which he was led or lifted during the acclamation and coronation, showing that it was his by right and general consent.

The new ideology is expressed particularly clearly in

The King's Mirror

, composed in Norway, probably in the 1250s. This work deals directly with the problem of regicide. Discussing God's different judgments of the evil King Saul and the good King David, the author points out that despite Saul's evil character and God's rejection of him, David saved his life when he had the opportunity to kill him, adding that he was not allowed to kill the Lord's anointed. At the end of the work, the author shows the king before God's seat of judgment, and declares that an evil king will get his punishment from God, not from his subjects. In another passage the author accordingly states that the king represents God on earth where, like God, he is the lord of life and death: it is only he and his representatives who are allowed to kill other humans. This last passage should not be understood as an expression of the king's arbitrary power but as the introduction of the idea of a public power with rights and duties different from those of ordinary people, in other words as an explicit expression of the ideas that brought an end to the practice of regicide.

However, protection against murder was not the same as protection against opposition or even deposition. Kings during the following period potentially faced two problems. One was younger brothers, who were now excluded from the throne as long as their elder brother lived, but had to be provided for in accordance with their status, normally with a part of the country held as a fief. The other was opposition from the Church and/or the aristocracy, which rested on the idea that a king should rule in accordance with the interests of the people, in practice mainly the aristocracy. However, this opposition increasingly took legal forms. It might be violent, but not until peaceful means had been exhausted. Violence had to be preceded by a formal declaration of war or a renunciation of obedience, and its use normally preceded by prolonged negotiations. Above all, resistance to the king was increasingly formalized; it had to be carried out by an organized body, eventually

the council of the realm. This combination of lawful resistance and kingship by the grace of God may at first seem paradoxical, but there is a connection between the two. The doctrine of the divine origin of kingship was the same in Byzantium and the Muslim world, but there the murder of rulers and coups d'état were commonplace. This was not the case in the West, and the explanation seems to be that here there was a lawful way of opposing the ruler. As these conflicts are particularly characteristic of the period of the Kalmar Union, however, they will be dealt with later.

Eventually, members of the aristocracy received protection similar to that of the king. The saga of King Sverre lists sixteen members of the top aristocracy who were killed, together with King Magnus Erlingsson, in the 1184 battle of Fimreite in Norway. Captive aristocrats were frequently executed in internal conflicts in all three countries, and if they were not, the reason should probably be sought in tactical considerations rather than rules of chivalry. In the later Middle Ages, however, aristocrats profited from similar rules as the king. Although without covering up the tricks and stratagems of the dukes, the early-fourteenth century

Chronicle of Erik

is full of references to the chivalrous treatment of captives and honorable burials of fallen enemies. The common European rules of chivalrous behavior towards aristocratic enemies seem in most cases to have been followed in internal as well as external wars. Thus, in contrast to England, where from the late thirteenth century onwards increased respect for the king led to stricter punishments for treason or rebellion, even for aristocratic prisoners, the rules were similar for the treatment of kings and aristocrats in Scandinavia.

The changes resulting from this stabilization of the monarchy can be summarized in the terms “centralization” and “bureaucratization.” The formation of dynasties and the change in the status of rulers was accompanied by the development of royal

and ecclesiastical administrations, which replaced personal and patronal rulership with a government that was in some degree bureaucratic; or that at least exhibited some elements of bureaucracy. The rise of the Scandinavian kingdoms is thus an example of the export of some central features of the civilization that was forming at the time in Western Christendom, notably a royal and an ecclesiastical organization, which entailed the centralization of important social functions such as religion, law, and warfare.

Religion: The Introduction of Christianity

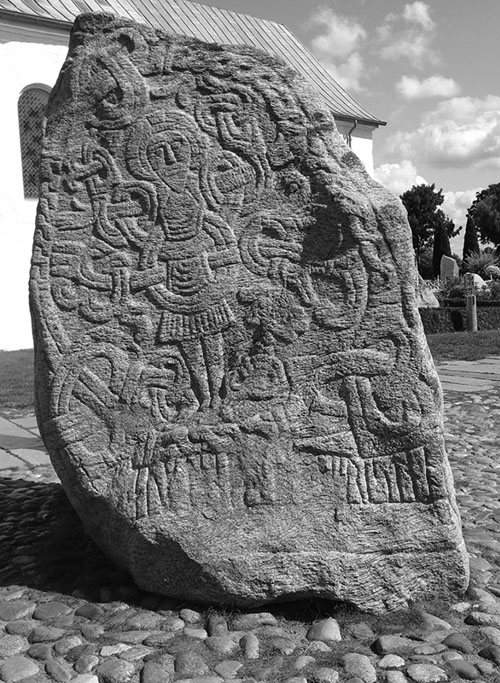

The old royal center at Jelling in Jutland stands as a visual monument of the transition from paganism to Christianity in Denmark. It comprises two burial mounds, two rune stones, and a Christian church. One of the mounds contains a pagan grave, probably that of King Gorm (d. c. 950), who raised a monument to his wife, Queen Tyra, in one of the rune stones. The other mound, possibly intended for Gorm's son Harald Bluetooth (d. 986), is empty, but Harald is present on the other rune stone, which celebrates his conquest of Denmark and Norway and his conversion of Denmark, underneath a carving of Christ. The inscription runs: “King Harald let carve these runes after Gorm his father and Tyra his mother, Harald who won all Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.”

The Jelling monument is one of the most important testimonies to the Christianization of Scandinavia and its inscription one of the relatively few contemporary sources for it. What does it mean that Harald “made the Danes Christian”? Another contemporary source, the German chronicler Widukind of Corvey (c. 967/68), attributes their final conversion to a German cleric and later bishop, Poppo. Although the Danes had been Christian for a long time, they continued to practice pagan rituals. During a discussion at a party at the king's court, some of those present claimed that although Christ was a god, there were also other and mightier gods, who were able to produce greater signs and miracles. To this Poppo answered that Christ was the only God and that the pagan gods were without power. King Harald then asked Poppo if he could prove the truth of his faith. Poppo accepted the challenge and successfully carried hot iron as evidence, which convinced the king to convert, to honor the Church, and to forbid pagan cult.

Figure 3.

Jelling Stone (Denmark). The picture shows the victorious Christ, surrounded by ornaments interpreted as the Tree of Life or possibly the cross. This style ornamentation was current in Scandinavia ca. 880â1000 and is referred to as the Jelling style. The stone has three sides; the two not depicted here show, respectively, a lion (a Biblical symbol of Christ), and the inscription quoted in the text. Photo: P. Thomsen. Dept. of Special Collections, University of Bergen Library.