Cross and Scepter (13 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

From the king's point of view, bishops and prelates were desirable officers as they had administrative skills and legal learning, as well as the advantage that their offices were not hereditary. If the king could influence their elections, as was often the case, he might thus gain subordinates who owed their office to him and who could be replaced by others equally beholden to him. The prospect of a bishopric would also serve to make royal service more attractive. With such links to the king, the prelates also had the same interest as their counterparts in the secular aristocracy in national independence; for there was no guarantee that they would receive similar favors from the king of the neighboring country. This does not mean that bishops and archbishops never opposed the national king or allied with other kings against him, but such cases were the exception rather than the rule.

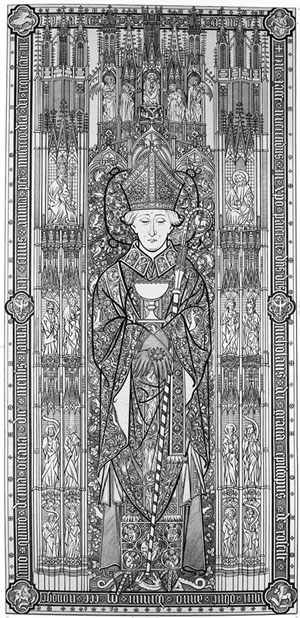

Figure 7.

Illustration after the tombstone of Niels Jakobsen Ulfeldt, Bishop of Roskilde, d. January 18, 1395. The bishop wears full liturgical clothes and episcopal insignia: a miter, a staff, and the gloves with the ring, while the chalice, symbolizing the Eucharist, appears on his breast. Drawing: Søren Abildgaard, 1764. Lithograph by R. Hartnack, from J. B. Løffler,

Gravstenene i Roskilde Kjøbstad

(Copenhagen, 1885). Photo: Dept. of Special Collections, University of Bergen Library.

Justice: Royal and Ecclesiastical Legislation and Courts of Law

In the saga of Egil Skallagrimsson, composed in the first half of the thirteenth century, the protagonist Egil goes to Norway to take possession of the inheritance of his wife Asgjerd, whose father

has just died. To achieve his aim, Egil has to challenge his brother-in-law, Berg-Onund, who claims that Asgjerd has no right to inherit, because she descends from slaves and was not born in legitimate marriage. The two parties meet at Gulating, the legal assembly (

thing

) in Western Norway. They present their case before the judges, thirty-six altogether (=12 Ã 3), who are seated in the middle of the plain where the

thing

is assembled, surrounded by sacred ropes. Egil seems to have a good chance, as his friend Arinbjørn controls two thirds of the judges. In accordance with the law, Egil presents twelve men willing to swear to his wife's legitimate birth. However, Egil is the king's enemy, while Berg-Onund is his friend, and the king is present at the

thing.

The king is reluctant to intervene, but his wife, Gunnhildâthe classic wicked queen of the sagasâhas her men attack the court, cutting the sacred ropes and chasing the judges away. A strong case and lawful witnesses are of no use; the king and the queen are able to prevent a settlement. We may in addition note a reference in the saga to Arinbjørn's control of the court. Would this have been a more important factor than Asgjerd's legitimate birth and Egil's oath-helpers if the king and queen had not been there? Was the problem from Egil's point of view not that the queen interrupted a legal proceeding, but that she cancelled the advantage Egil had because of his friendship with Arinbjørn?

The account in the saga is of course no unimpeachable record of what went on at the mid-tenth century Gulating. However, the thirteenth-century Icelandic family sagas and the contemporary

Sturlunga Saga

give ample evidence of legal practice in similar situations, before the submission to the king of Norway and the reception of Norwegian law. Although we cannot apply conclusions drawn from pre-state Iceland to the rest of Scandinavia in the early Middle Ages, the early laws from these countries indicate that legal practices there were in many respects similar in the early period, until around the mid-twelfth century.

First, the system was based on formal rules and procedures and relied on the testimony of formally appointed witnesses or oath-helpers. Thus, when sued, a defendant had to prove his case by compurgation, aided by between one and eleven co-jurors, the more jurors the more serious the accusation. In some particularly serious cases, he or she might also have to undergo an ordeal, by carrying or walking on hot iron or by fishing an object out of a boiling kettle (the latter ordeal was mostly used for women). Witnesses were widely used, though their function differed from that of witnesses as we know them in later courts. All contracts and agreements were entered in the presence of formally summoned witnesses who had the same function in an oral society as written documents in literate ones. Such witnesses would then be required to testify in court.

Secondly, justice was not administered by public authorities acting independently but always as a resolution of conflicts between private parties. There was no distinction between civil and public law. Thus, a murder case would be dealt with in the same way as a dispute over property and would be settled by the killer or his kinsmen paying compensation to an injured party. There was no police and no office of a public prosecutor; it was up to the individual to claim his or her rights.

Thirdly, there was a thin line between legal and extralegal disputes. Examples like the one in

Egils Saga

of the stronger party breaking off the proceedings by the use of violence abound. Sufficient manpower was therefore needed to win a court case. Moreover, at least in the Icelandic sagas, a court decision rarely constitutes the final solution to a conflict, but is rather a means to achieve an advantage over an adversary, which may eventually lead to a favorable settlement.

All this changed over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Church introduced the idea of crimes against God and society, and took steps to punish them, as is evident from passages

in the oldest Norwegian laws about punishment for failing to respect the ecclesiastical holidays. For a long time, such prosecutions had to be conducted within the framework of the old judicial system, where the bishop or his representative acted like any other individual who felt himself wronged, but it led gradually to the development of ecclesiastical prosecution and courts of law. Public justice was based on the idea that certain acts were offenses against God, society, and the social order and had to be punished. It was not only damage done to an individual or a kindred that had to be repaired or compensated. Thus, a concept of crime evolved and, beyond that, the idea of subjective guilt, which meant that not only the act itself but its background and the criminal's intentions had to be taken into account. Crimes committed as the result of weakness, without knowledge of the seriousness of the act or under duress, should be punished mildly, whereas those done out of haughtiness or malice should be punished severely. This is not to suggest that the distinction between intentional and unintentional acts was unknown in the previous period, but such a distinction was more difficult to apply when there was no judge above the parties.

Ideas introduced by the Church were eventually adopted by the king. An early example is the peace legislation from Norway in the 1160s and Denmark around 1170, which identified acts that could not be atoned for by fines but instead rendered the criminal an outlaw. Outlawry in itself is probably older as a punishment for actions that affected the whole community, but these particular laws are so similar to decrees from the first three Lateran Councils and to German peace legislation that there can be no doubt about the influence. The crimes mentioned are killing under particularly aggravating circumstances, sorcery, highway robbery, rape, and the seduction of women. In practice, a criminal could atone for even such a crime by fines; but he would have to “buy his peace” from the king at a heavy price. (The expression

indicates that he had lost his “peace” or right to remain in the country because of his crime, and would have to buy it back.) The king followed up by punishing killings, theft, violence, and other offenses against the public order. Although in the beginning, the king only demanded fines for offenses against himself, he eventually did so for most acts defined as crimes, although on the condition that the offended party had sued.

An important step in this direction was taken in Denmark with King Knud VI's 1200 ordinance against homicide. In his 1260 ordinance, King HÃ¥kon HÃ¥konsson of Norway forbade revenge on any other than the killer himself, whereas earlier, his relatives had also been legitimate targets. HÃ¥kon also decreed that an offer of compensation had to be accepted, whereas earlier it had been up to the injured party to choose between revenge and compensation. HÃ¥kon's successor Magnus, nicknamed the Lawmender, went one step further and almost completely banned revenge.

A change in the field of evidence paralleled the new distinction between private and public law. The Church had long distrusted the compurgation oath, which was rarely used in canon law. A papal letter of 1218 to the archbishop of Lund denounces it as a pestilence and contrary to all justice. Nevertheless, compurgation continued to be widely used in Scandinavia throughout the Middle Ages, although it was to some extent supplemented by other forms of evidence. By contrast, ordeals were eventually abolished by a decision at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, which forbade the clergy to participate in them. In practice, they disappeared: in Denmark soon after 1215, in Norway in 1247, and in Sweden in the 1250s or 60s, though in Sweden the ban had to be repeated as late as the 1320s. Now, instead of a defendant proving his innocence by formal means, both parties had to present their evidence before the judge or judges who would decide on this basis which party was in the right. The new principles are expressed in Denmark in the Law of Jutland in 1241 and in Norway

in the Code of the Realm of 1274, with some anticipation in previous legislation. Thus, in the latter, a defendant accused of murder has the opportunity to prove his innocence if he can produce twelve men who are willing to swear that they were present with him at a place so far away from the site of the crime that he could not have committed it. Here the compurgators are not only men of good reputation, but provide the necessary information to give the accused person an alibi, thus resembling witnesses rather than oath-helpers.

These changes in the understanding of crime and legal evidence necessitated changes in the administration of justice. Skill and education were needed both to evaluate the evidence presented in court when it was no longer formal, and to mete out punishment in accordance with motives and circumstances in criminal cases. A court of law also needed authority to intervene against powerful men in local society. Consequently, the administration of justice was professionalized. This applied above all to the ecclesiastical courts of law, where the bishop was the highest judge. He often had a university education in law and in addition often delegated his judicial powers to officers with a similar education, to his deputy (Lat.

officialis

) or to provosts or archdeacons. However, ecclesiastical courts continued to use local people, mostly as witnesses but to some extent also as judges.

Secular courts made greater use of ordinary non-professional people. Both in Denmark and Norway, the judges were normally committees of local men, similar to English juries, in Denmark either permanent committees or committees appointed by the plaintiff. Norwegian juries were selected from the local assemblies, probably by the lawman (

lagmann,

Old Norse

lá»gmaðr

), a royal judge appointed by the king. From the second half of the thirteenth century on, the country was divided into ten districts with one such judge in each. The lawman was originally a member of the local assembly who was well versed in the law, and who

was supposed to quote the relevant passage from it for the assembly to use in its decisions. Later, he was appointed by the king. He might in some cases judge alone, but in cases of serious crimes normally acted together with a local jury; if the two disagreed, the case had to be appealed to the king. According to the Code of the Realm, only the king might set aside the lawman's decision, “for he is above the law.” In this way, jurisdiction was governed by the king in a much more direct sense in Norway than in either Denmark or Sweden. Although local society played a prominent part in all three countries and most cases were probably decided either by local juries or local arbitration, there was a direct link from the king to the local courts in Norway, which was absent in the other Scandinavian countries.

In Denmark, the local assemblies (

herredsting

) formed the courts of law. These had originally been administered by the peasant landowners, but beginning in the thirteenth century they came increasingly under the control of the aristocracy, which during this period acquired ownership of most of the land, while the majority of the peasants became their tenants. The new landowners eventually became the patrons of their tenants, while at the same time they also received the fines their tenants paid when convicted in court. A tenant would thus have to face the court with the knowledge that his patron would profit from his conviction!

Nevertheless, there is evidence that the sway of royal justice also expanded during the second half of the thirteenth century and the first decades of the fourteenth, both in Denmark and Sweden. Special royal courts of law emerged with jurisdiction above the local courts. They served partly as courts of appeal and partly as courts of the first instance, though the latter mostly for the aristocracy and the upper classes. While in the 1282 statute of the diet of Nyborg, issued in favor of the aristocracy, the king promises to bring his cases before the ordinary local courts, the

statute issued by King Christoffer II at his accession in 1320, which is equally aristocratic in its contents, takes a special royal court of law for granted. A royal court of law also developed in Sweden in connection with the peace legislation. As for Iceland, the main changes came with the island's submission to the king of Norway, which led to new legislation, based on similar principles to that enacted in Norway (in 1271â1273 and in 1281), and to a system of public justice administered by royal officials. There were however already detectable tendencies in this direction in the principalities formed by the great magnates in the first half of the century.