Collected Prose: Autobiographical Writings, True Stories, Critical Essays, Prefaces, Collaborations With Artists, and Interviews (73 page)

Authors: Paul Auster

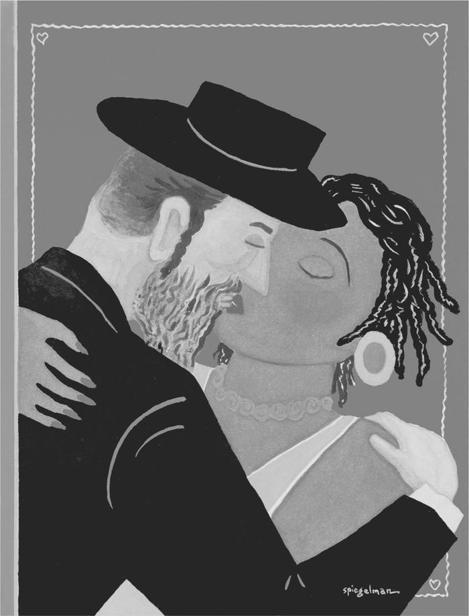

It was a bad time for the city. Crown Heights, an impoverished neighborhood in Brooklyn inhabited by African-Americans and Orthodox Jews, was on the brink of a racial war. A black child had been run over by a Jew, a Jew had been murdered in retaliation by an angry mob of blacks, and for many days running a fierce agitation dominated the streets, with threats of further violence from both camps. The mayor at the time, David Dinkins, was a decent man, but he was also a cautious man, and he lacked the political skill needed to step in quickly and defuse the crisis. (That failure probably cost him victory in the next election—which led to the harsh regime of Rudolph Giuliani, who served as mayor for the next eight years.) New York, for all its ethnic diversity, is a surprisingly tolerant city, and most people make an effort most of the time to get along with one another. But racial tensions exist, often smoldering in silence, occasionally erupting in isolated acts of brutality—but here was an entire neighborhood up in arms, and it was an ugly thing to witness, a stain on the democratic spirit of New York. That was when Spiegelman was heard from, the precise moment when he walked into the battle and offered his solution to the problem.

Kiss and make up

. His statement was that simple, that shocking, that powerful. An Orthodox Jew had his arms around a black woman, the black woman had her arms around the Orthodox Jew, their eyes were closed, and they were kissing. To round out the Valentine’s Day theme, the background of the picture was solid red, and three little hearts floated within the squiggly border that framed the image. Spiegelman wasn’t taking sides. As a Jew, he wasn’t proposing to defend the Jewish community of Crown Heights; as a practitioner of no religion, he wasn’t voicing his support of the African-American community that shared that same miserable patch of ground. He was speaking as a citizen of New York, a citizen of the world, and he was addressing both groups at the same time—which is to say, he was addressing all of us. No more hate, he said, no more intolerance, no more demonizing of the other. In pictorial form, the cover’s message was identical to an idea expressed by W.H. Auden on the first day of World War II:

We must love one another or die.

Since that remarkable debut, Spiegelman has continued to confound our expectations, consciously using his inventiveness as a destabilizing force, a weapon of surprise. He wants to keep us off balance, to catch us with our guard down, and to that end he approaches his subjects from numerous angles and with countless shadings of tone: mockery and whimsy, outrage and rebuke, even tenderness and laudatory affection. The heroic construction-worker mother breast-feeding her baby on the girder of a half-finished skyscraper; turkey-bombs falling on Afghanistan; Bill Clinton’s groin surrounded by a sea of microphones; college diplomas that turn out to be help-wanted ads; the weirdo hipster family as emblem of cross-generational love and solidarity; the crucified Easter bunny impaled on an IRS tax form; the Santa Claus and the rabbi with identical beards and bellies. Unafraid to court controversy, Spiegelman has offended many people over the years, and several of the covers he has prepared for

The New Yorker

have been deemed so incendiary by the editorial powers of the magazine that they have refused to run them. Beginning with the Valentine’s Day cover of 1993, Spiegelman’s work has inspired thousands of indignant letters, hundreds of canceled subscriptions and, in one very dramatic instance, a full-scale protest demonstration by members of the New York City Police Department in front of the

New Yorker

offices in Manhattan. That is the price one pays for speaking one’s mind—for drawing one’s mind. Spiegelman’s tenure at

The New Yorker

has not always been an easy one, but his courage has been a steady source of encouragement to those of us who love our city and believe in the idea of New York as a place for everyone, as the central laboratory of human contradictions in our time.

Then came September 11, 2001. In the fire and smoke of three thousand incinerated bodies, a holocaust was visited upon us, and nine months later the city is still grieving over its dead. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, in the hours and days that followed that murderous morning, few of us were capable of thinking any coherent thoughts. The shock was too great, and as the smoke continued to hover over the city and we breathed in the vile smells of death and destruction, most of us shuffled around like sleepwalkers, numb and dazed, not good for anything. But

The New Yorker

had an issue to put out, and when they realized that someone would have to design a cover—the most important cover in their history, which would have to be produced in record time—they turned to Spiegelman.

That black-on-black issue of September 24 is, in my opinion, Spiegelman’s masterpiece. In the face of absolute horror, one’s inclination is to dispense with images altogether. Words often fail us at moments of extreme duress. The same is true of pictures. If I have not garbled the story Spiegelman told me during those days, I believe he originally resisted that iconoclastic impulse: to hand in a solid black cover to represent mourning, an absent image to stand as a mirror of the ineffable. Other ideas occurred to him. He tested them out, but one by one he rejected them, slowly pushing his mind toward darker and darker hues until, inevitably, he arrived at a deep, unmodulated black. But still that wasn’t enough. He found it too mute, too facile, too resigned, but for want of any other solution, he almost capitulated. Then, just as he was about to give up, he began thinking about some of the artists who had come before him, artists who had explored the implications of eliminating color from their paintings—in particular Ad Reinhardt and his black-on-black canvases from the sixties, those supremely abstract and minimal anti-images that had taken painting to the farthest edge of possibility. Spiegelman had found his direction. Not in silence—but in the sublime.

You have to look very closely at the picture before you notice the towers. They are there and not there, effaced and yet still present, shadows pulsing in oblivion, in memory, in the ghostly emanation of some tormented afterlife. When I saw the picture for the first time, I felt as if Spiegelman had placed a stethoscope on my chest and methodically registered every heartbeat that had shaken my body since September 11. Then my eyes filled up with tears. Tears for the dead. Tears for the living. Tears for the abominations we inflict on one another, for the cruelty and savagery of the whole stinking human race.

Then I thought:

We must love one another or die

.

June 2002

Invisible Joubert

Some writers live and die in the shadows, and they don’t begin to live for us until after they are dead. Emily Dickinson published just three poems during her lifetime; Gerard Manley Hopkins published only one. Kafka kept his unfinished novels to himself, and if not for a promise broken by his friend Max Brod, they would have been burned. Christopher Smart’s Bedlamite rant,

Jubilate Agno

, was composed in the early 1760s but didn’t find its way into print until 1939.

Think of how many writers disappeared when the Library of Alexandria burned in

AD

391. Think of how many books were destroyed by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages. For every miraculous resurrection, for every work saved from oblivion by free-thinkers like Petrarch and Boccaccio, one could enumerate hundreds of losses. Ralph Ellison worked for years on a follow-up novel to

Invisible Man

, then the manuscript burned in a fire. In a fit of madness, Gogol destroyed the second part of

Dead Souls

. What we know of the work of Heraclitus and Sappho exists only in fragments. In his later years Herman Melville was so thoroughly forgotten that most people thought he was dead when his obituary appeared in 1891. It wasn’t until

Moby Dick

was discovered in a second-hand bookshop in 1920 that Melville came to be recognized as one of our essential novelists.

The afterlife of writers is precarious at best, and for those who fail to publish before they die—by choice, by happenstance, by sheer bad luck—the fate of their work is almost certain doom. The American poet Charles Reznikoff reported that his grandmother threw out every one of his grandfather’s poems after he died—an entire life’s work discarded with the trash. More recently, the young John Kennedy O’Toole committed suicide over his failure to find a publisher for his book. When the novel finally appeared, it was a critical success. Who knows how many unread masterpieces are hidden away in attics or moldering in cellars? Without someone to defend a dead writer’s work, that work could just as well never have been written. Think of Osip Mandelstam, murdered by Stalin in 1938. If his widow, Nadezhda, had not committed the entire body of his work to memory, he would have been lost to us as a poet.

There are dozens of posthumous writers in the history of literature, but no case is stranger or more obscure than that of Joseph Joubert, a Frenchman who wrote in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Not only did he not publish a single word while he was alive, but the work he left behind escapes clear definition, which means that he has continued to exist as an almost invisible writer even after his discovery, acquiring a handful of ardent readers in every generation, but never fully emerging from the shadows that surrounded him when he was alive. Neither a poet nor a novelist, neither a philosopher nor an essayist, Joubert was a man of letters without portfolio whose work consists of a vast series of notebooks in which he wrote down his thoughts every day for more than forty years. All the entries are dated, but the notebooks cannot be construed as a traditional diary, since there are scarcely any personal remarks in it. Nor was Joubert a writer of maxims in the classical French manner. He was something far more oblique and challenging: a writer who spent his whole life preparing himself for a work that never came to be written, a writer of the highest rank who paradoxically never produced a book. Joubert speaks in whispers, and one must draw very close to him to hear what he is saying.

He was born in Montignac (Dordogne) on May 7, 1754, the son of master surgeon Jean Joubert. The second of eight surviving children, Joubert completed his local education at the age of fourteen and was then sent to Toulouse to continue his studies. His father hoped that he would pursue a career in the law, but Joubert’s interests lay in philosophy and the classics. After graduation, he taught for several years in the school where he had been a student and then returned to Montignac for two years, without professional plans or any apparent ambitions, already suffering from the poor health that would plague him throughout his life.

In May 1778, just after his twenty-fourth birthday, Joubert moved to Paris, where he took up residence at the Hôtel de Bordeaux on the rue des Francs-Bourgeois. He soon became a member of Diderot’s circle, and through that association was brought into contact with the sculptor Pigalle and many other artists of the period. During those early years in Paris he also met Fontanes, who would remain his closest friend for the rest of his life. Both Joubert and Fontanes frequented the literary salon of the countess Fanny de Beauharnais (whose niece later married Bonaparte). Other members included Buffon, La Harpe, and Restif de la Bretonne.

In 1785, Fontanes and Joubert attempted to found a newsletter about Paris literary life for English subscribers, but the venture failed. That same year, Joubert entered into a liaison with the wife of Restif de la Bretonne, Agnès Lebègue, a woman fourteen years his senior. But by March 1786 the affair had ended—painfully for Joubert. Later that year, he made his first visit to the town of Villeneuve and met Victoire Moreau, who would become his wife in 1793. During this period Joubert read much and wrote little. He studied philosophy, music, and painting, but the various writing projects he began—an appreciation of Pigalle, an essay on the navigator Cook—were never completed. For the most part, it seems that Joubert watched the world around him, cultivated his friendships, and meditated. As time went on, he turned more and more to his notebooks as the place to develop his thoughts and explore his inner life. By the late 1780s and early 1790s, they had become a serious daily enterprise for him. At first, he looked upon his jottings as a way to prepare himself for a larger, more systematic work, a great book of philosophy that he dreamed he had it in him to write. As the years passed, however, and the project continued to elude him, he slowly came to realize that the notebooks were an end in themselves, eventually admitting that “these thoughts form not only the foundation of my work, but of my life.”

Joubert had long been a supporter of revolutionary views, and when the Revolution came in 1789, he welcomed it enthusiastically. In late 1790, he was named Justice of the Peace in Montignac, a position that entailed great responsibilities and made him the leading citizen of the town. By all accounts, he fulfilled his tasks with vigilance and fairness and was widely respected for his work. But he soon became disillusioned with the increasingly violent nature of the Revolution. He declined to stand for reelection in 1792 and gradually withdrew from politics.