Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (6 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

I followed T. Rex around London with Zaza. We used to go to every gig. We couldn’t actually go to the concerts – we only saw Bolan play twice because we were broke – but we used to stand outside the stage door and try to talk to him or June Child, his wife. We were fascinated by June – I changed my name to Viv Child for a while. I saw pictures in

Melody Maker

of a mad hatters’ tea party her and Marc had in their garden – I was so jealous – they were in top hats and beautiful clothes, they’d set up tables and chairs under the trees, it was a different world. June was much more interesting to me than other rock girlfriends because she wasn’t druggy and she worked in a record company. Me and Zaza talked to her once outside the Lyceum, she stopped and had a few words with us, but she didn’t like it when we talked to Marc, she’d call him away – ‘Marc! Come on. We have to go in now.’

I remember John Peel playing ‘Ride a White Swan’ on his radio show late one night. The next morning I was going away on a Woodcraft camp to Yugoslavia (we usually went to communist countries) for a couple of weeks, and I said to Mum, ‘That song is going to be a hit.’ I thought it was great, I liked it better than his old folky fairy stuff, it was catchier, more of a pop song. When I got back from Yugoslavia two weeks later it had entered the charts and ten weeks later it was at number two. It was January 1971 and I was seventeen years old. Lots of my male friends were appalled that I liked T. Rex and pop music, but I love a good song. Whatever its genre, a good song is a good song.

David Bowie’s album

Hunky Dory

was full of good songs, I played it to lots of people at school. One Turkish boy said, ‘Viv, his voice really turns me on. I think I might be gay.’

I’d made a friend called Alan Drake, from Southgate, he was very pretty with long straight dark brown hair and sensual lips: we discovered Bowie together. We saw him loads of times in little college halls. The best time was in the Great Hall (not very big) at Imperial College in South Kensington on 12 February 1972. Bowie was wearing tight white silk trousers and a patterned silk bomber jacket open to his waist, showing his bony hairless chest. Mick Ronson, the guitarist, looked uncomfortable in his flamboyant clothes, like a docker dressed up; he was too masculine, couldn’t carry off the androgyny. I didn’t know he was a brilliant guitarist, I just thought he couldn’t pull off the look.

Halfway through the show, Bowie climbed into the audience. I don’t know where he picked that up from, no one else I’d seen did that. None of us got it though, we didn’t realise you were supposed to lift him up and carry him along, everyone parted politely, thought he was off to the bog or something, and he fell on the floor, it was embarrassing. The gig wasn’t very crowded, so there weren’t enough people to do it anyway. He got up and walked around a bit. I leaned against the stage, trying to see where he’d gone, but the lights were in my eyes. Then I felt a hand grip my shoulder and Bowie heaved himself up on me. I nearly buckled – I wasn’t expecting it, I didn’t know what was happening. He climbed over me to get back on stage, kneeing me in the chest and treading on my head with his silk boxing boot – he didn’t care – he just had to get back up. He’s not as dainty as he looks.

Zaza and I went to loads of Hawkwind gigs too. She liked them more than me, and she’d chat to Dave Brock, the guitarist and synth player, before a show. I was too shy and just hung back behind her but he was very kind and friendly. There was a pretty girl with them called Stacia who danced completely naked whilst they played; she’d paint her body and light projections would swirl over her skin. We chatted to her a few times and she was very friendly too. Hawkwind got to recognise me and Zaza and often gave us a lift back into central London in the back of their van. They never made a move on us or said anything sexual, they were very gentlemanly. Only once did one of them ask for my phone number, he was the new bass player, but I didn’t have a phone so he gave me his. I never called. I met him years later when the Slits filmed a video at his recording studio in Wales. His name was Thomas Crimble and he was married to a girl called Nutkin. I reminded him (when Nutkin wasn’t around) of that drive in the van, he thought for a minute then said, ‘Yes, yes, I remember!’ It was obvious he didn’t though.

Once me and Zaza were so bored that we decided to hitch-hike across London, anywhere it took us. We ended up at the Hard Rock Café in Marble Arch. It hadn’t been open long and we wanted to have a look at it. We went in and looked at the menu but the burgers were so expensive – they were ten times the price of a Wimpy – we pretended we were just looking around and didn’t want to eat there. We hung around outside, sticking our thumbs out, trying to get a lift back home. A bunch of guys came out of the cafe and said they were going to get their van and they’d give us a lift a bit further into town. They were in a band called America. Funny-looking lot, checked shirts, denim flares, a bit country bumpkin-ish; very sweet though. They were going to a party and asked us if we wanted to come. We said, ‘No thanks, just drop us here in Shaftesbury Avenue at this cafe, the Lucky Horseshoe.’ We often went there, sometimes they gave us free soup. We sat down and watched the van drive away. Then we looked at each other.

Are we mad? What were we thinking? We’ve got nothing in the world to do, nowhere to go, no money and we’ve turned down a party with an American group who have a hit with ‘Horse with no Name’

. It took us months to get over that missed opportunity.

I felt so near to and yet so far from music. I thought that actually

being

a musician was something you were born to, a gift you either had or didn’t have. A few of my girlfriends had parents or sisters that were classical musicians: I saw them practising five hours a day and knew I wasn’t the sort of person to work that hard at anything. It looked like drudgery, plodding up and down scales for hours on end. As for people I knew who played electric guitar, I thought it was something you had to have a willy to do, or at least be a genius like Joni Mitchell or worthy like Joan Baez – and preferably American of course. I liked the look of Liquorice and Rose, the two girls in the Incredible String Band, but the whole set-up seemed a bit cliquey. No way in there. Melanie was fun, but eccentric, with her wobbly voice and clever lyrics. Sandie Shaw was more ordinary; she worked in an office before she was discovered and had a working-class London accent – but she was a singer and didn’t play an instrument.

To keep my mind occupied, I fantasised about musicians. There was nothing else to think about. We had no TV, and there was nothing on it anyway, I wasn’t missing much. (We eventually got a second-hand black-and-white set but the living room was so cold that we had to sit under a pile of old army coats, blankets and sleeping bags to watch it. It just wasn’t worth the effort.) A children’s feature film came out in the cinema once a year at Christmas, not many people had telephones (landlines), there was nowhere to go: youth clubs were a joke and I wasn’t interested in lessons, except art and English. Music and guys in bands were a way to let your imagination loose. I’d fantasise that Donovan or John Lennon was my brother, or that I’d bump into Scott Walker and he’d fall in love with me; cooking up an interesting world in my head.

I studied record covers for the names of girlfriends and wives. That’s how I connected girls to the world I wanted to be in. I scanned the

thank yous

and the lyrics, looking for girls’ names. Especially if I fancied the musician. What are these girls like who go out with poets and singers? What have they got that I haven’t?

I read the book

Groupie

by Jenny Fabian and I’m ashamed to say I thought it sounded OK, being a groupie. But I knew I wasn’t witty, worldly or beautiful enough to even be that. The only other way left for a girl to get into rock and roll was to be a backing singer and I couldn’t sing.

Every cell in my body was steeped in music, but it never occurred to me that I could be in a band, not in a million years – why would it? Who’d done it before me? There was no one I could identify with. No girls played electric guitar. Especially not ordinary girls like me.

15 HELLO, I LOVE YOU

1970

There I went again, building up a glamorous picture of a man who would love me passionately the minute he met me, and all out of a few prosy nothings.

Sylvia Plath,

The Bell Jar

I’ve given up on becoming a pop singer since Dad told me I wasn’t chic enough and I haven’t managed to find a way to meet those beautiful people that I see floating along Kensington High Street every Saturday – the leggy girls with long blonde hair and astrakhan boots holding hands with pretty boys in tapestry bell-bottoms and plum-coloured velvet jackets – but I still daydream about falling in love and escaping these dreary doldrums I’m stuck in.

I’m sixteen, sitting in Crouch End public library, wearing a dress I bought from Kensington Market; it’s a dark purple cotton maxi dress with bell sleeves and a tight laced bodice. I’ve got no shoes on my dirty feet.

A shadow falls across the page of the book I’m reading –

I Start Counting

, by Audrey Erskine Lindop – I look up to see a handsome boy standing in front of me. He’s a few years older than I am, wearing a dark blue velvet jacket and a flowery shirt. He looks at me sadly with his beautiful blue eyes. I can’t believe it: this is what I’ve always hoped and believed would happen – a handsome guy looks at me and knows instantly that I’m his soul mate. I gaze back at him. The boy doesn’t speak; this is so intense I think I might explode. Gradually I become aware he’s holding something in front of his chest. I wrench my gaze from his beautiful face and look down. It’s a newspaper. The words swim, I can’t focus … I feel sick, it’s all too much, the excitement, the romance. I look back up at him and smile, there’s a slight change in his expression, a little cooler; I look down again. The headline on the paper is

Jimi Hendrix Dead

. When he sees I’ve registered the enormity of the occasion, the boy walks away. I’m devastated, not because Jimi Hendrix is dead, but because the messenger isn’t my true love.

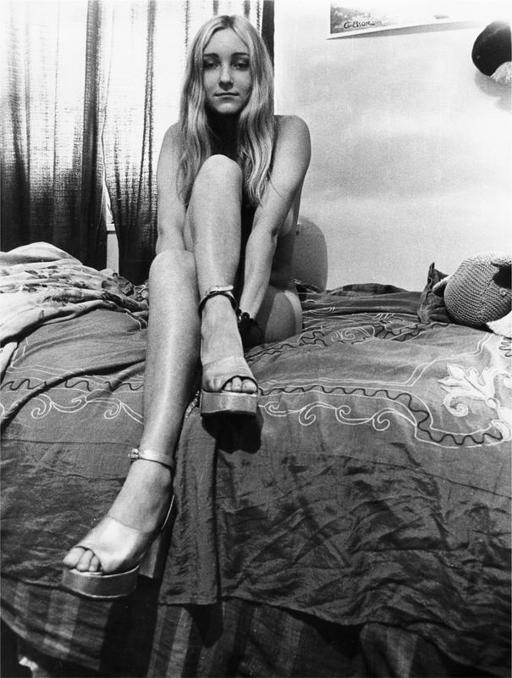

Sixteen years old, peroxide hair, Ravel shoes. Tan and bracelet from Greece. Blue knitted elephant, ‘Ellie’, just seen on bed. Not as grown up as I think. 1970

16 AMSTERDAM

1970

Me and Zaza run down Clarendon Road in Turnpike Lane, away from my tiny two-up two-down red-brick council house, past the iron gasworks and abandoned cars, towards freedom and adventure. It’s the summer holidays and we’re going to Amsterdam, on our own. Our rucksacks – with just a spare T-shirt and a packet of crisps at the bottom (we’ve forgotten to pack toothbrushes) – bounce up and down against our backs. We own one pair of jeans each – straight-legged Levi’s – which we’re wearing. I’m sixteen, she’s seventeen. We get to the corner and look up and down the high street, wondering which way to go.