Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (2 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

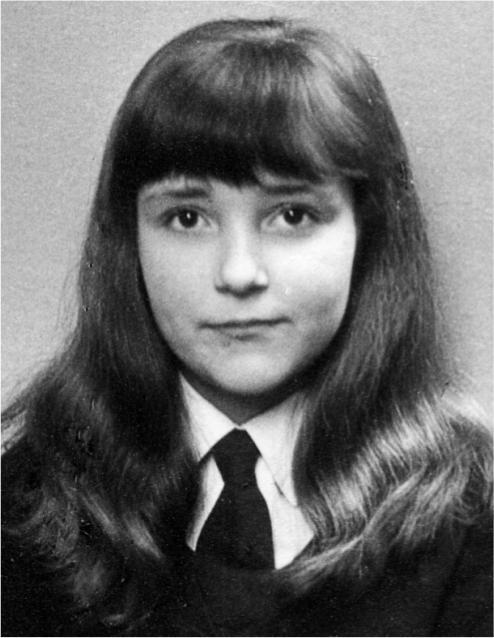

With my little sister

4 BAD BOYS

1962

The classroom door opens and in strides our headmaster, flanked by two identical, scruffy boys. Mr Mitchell announces to the class that the boys’ names are Colin and Raymond and they’ve been expelled from their last school for bad behaviour. He looks down at the twins and says:

‘St James’ is a church school: we believe in redemption and we are going to give you another chance.’

Colin and Raymond scowl up at him; they are not happy to be here or grateful for their second chance. They look at us clean-haired, well-behaved children in our maroon blazers, starched white shirts and striped ties with contempt. Their holey grey socks are crumpled around their ankles, they don’t wear silly short-shorts like all the other boys in my class – their shorts are long, right down to their scabby knees. They have greasy brown fringes hanging in their eyes. One of them has a scar on his freckled cheek. I think to myself,

Thank goodness, two good-looking boys at school at last

. I want to clap my hands together with glee. I don’t know where this thought comes from. I don’t recognise it. I’ve never cared about boys before, up until now they’ve been invisible to me, not important in my world. No one’s ever told me about bad boys, that they’re sexy and compelling, or to stay away from them. I work all this out by myself, today – at eight years old, in Class Three.

As our class marches in a crocodile through the leafy streets of Muswell Hill to the dining hall, I can’t take my eyes off these two delinquents. I want to drink them in. I screw my neck round and end up walking backwards just to stare at them. I’m disappointed that we’re not at the same table at lunch, but at least I’m directly behind Colin, sitting at a long trestle table with my back to him. I feel excited, a new kind of excitement, a bubbling, choking, gurgling feeling rises up from my navy-blue regulation school knickers into my chest. The effort of keeping this energy contained is revving me up even more. There’s only one thing I can think of doing to release the tension and get Colin’s attention: I poke him in the back. He takes no notice, so I poke him again. This time he spins round and snarls at me, baring his teeth like an animal under attack, but I’m buzzing on this new feeling and once he’s turned away from me, I poke him again.

In junior-school uniform, 1963

‘If you do that again I’ll smash your face in.’

I’ve never been threatened by a boy before and I don’t like it, I think I might cry. I have a feeling that this is not how it’s supposed to go if you like someone, but the adrenalin coursing through my blood obliterates my common sense. I can’t believe what I’m doing, I must be out of my mind, I risk everything, pushing all feelings of fear, pride and self-protection aside – I stretch out my arm and poke him again.

Colin swivels round. Everyone stops chattering and stares at us. I look for a teacher to come and save me but nobody’s near so I grip the bench tightly and stare straight back at Colin, waiting for the punch. His mouth twists into a sly smile.

‘I think she likes me.’

From this moment on, we are inseparable.

5 THE BELT

1963

But the child’s sob in the silence curses deeper Than the strong man in his wrath.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning,

‘The Cry of the Children’

I live with my mother, father and little sister, on the ground floor of my grandmother’s house in Muswell Hill, North London. The house smells of moth balls and we have to be quiet all the time, even in the garden –

I really identify with Anne Frank tiptoeing around her loft

– because of the nerves of Miss Cole, the tenant living on the top floor. Our flat has no living room and we share a bathroom with my grandmother. There are no carpets, just bare boards and a threadbare oriental rug in the kitchen. The only furniture we have is three beds, a mottled green Formica-topped dining table with tubular steel legs and four dining chairs covered with torn yellow plastic with hairy black stuffing poking out of the slits. This dining-room set was shipped over with us from Australia.

I can’t imagine what a happy home is like: parents cuddling and laughing, music playing, books on the shelves, discussions round the table? We don’t have any of that, but if Mum’s happy, I’m happy. The trouble is, she isn’t happy very often because my dad is odd and difficult and not as quick-minded as her – and also we’re poor. Every night I lie in bed listening through the wall to Mum tidying up the kitchen. She opens and closes cupboard doors, bangs pots and pans, and I try to interpret the sounds, to gauge by the strength of the door slams, the ferociousness of plates clattering together, the way the knives and forks are tossed into a drawer, if she’s in a good mood or not. Usually not. Occasionally I think,

That door was closed gently, that saucepan was put away softly, she’s feeling OK

, and I go off to sleep, happy.

Tonight, my eyes are swollen from crying and there are red welts across the back of my legs; the marks hurt so badly I have to lie on my side. Mum’s tucked me and my sister up in bed, given us both a kiss and turned off the light but I’m wide awake, straining to hear through the bedroom wall. I close my eyes, concentrating on the sounds to see if she’s got over the upset earlier. I can hear Dad talking to her.

What’s he doing in our home, this big hairy beast?

Lots of dads seem like that to me: awkward, in the way, out of place, filling up the rooms with their clumsy bodies. They should’ve gone off into the wild to hunt bison after their children were born and not come back; that’s how it was meant to be. My dad’s not like other dads though, he’s worse: hairy all over his body, with a stubbly chin that’s sprinkled with shaving cuts. He sticks little bits of toilet paper onto the nicks to stem the bleeding. Most of the time his neck and chin are covered in tiny white petals with red specks in the middle of each one. Halfway through the day, little red dots begin to reappear on his chin and he goes back to the sink for another shave. His deep voice, made even stranger by his French accent, rumbles and reverberates through the walls and he’s always clearing his throat of what sounds like great gobs of phlegm. He’s so … masculine, so … foreign – a cross between Fred Flintstone and a French version of Stanley Kowalski from

A Streetcar Named Desire

.

Earlier today two things happened, one that’s never happened before and one that happens a lot. We had people round, not friends – I don’t think Mum and Dad have any friends – but a couple of aunties and uncles. I was so excited, rushing round picking all the bits of fluff off the threadbare rug under the table –

Oh no! it’s so bare you can see right through to the strings

– as we don’t have a vacuum cleaner, straightening the chairs, making the beds. That’s the first time I’d seen our flat through other people’s eyes and I realised we lived in a dump.

By about three o’clock, everyone had arrived. I was in the kitchen putting homemade rock cakes onto a plate when I heard my dad telling a story about how him and Mum ran a fish-and-chip shop when they lived in Canada and everything that went wrong with it. They burnt the chips, made the batter out of the wrong flour, couldn’t feed a coach party that came in, told them to come back tomorrow. Mum and Dad laughed their heads off about it. That’s the thing that’s never happened before: Mum and Dad laughed together.

I stopped what I was doing and went to have a look. Standing in the kitchen doorway I gaped open-mouthed at them. Tears poured down my face and ran into my mouth, as I drank in this extraordinary sight. I was so happy and so scared, scared that I would never see such a wonderful thing again.

I never did

.

Four hours later I’m lying in the dark, listening. I can tell from the noises coming from the kitchen that Mum is angrier than usual and I know why. After everybody left, me or my sister, I can’t remember which, said something that irritated Dad, just something silly, but he flipped.

‘Go and get the belt.’

This happens a lot. I go to the cellar, open the door – no need to switch the light bulb on, I know this ritual by heart – and unhook the brown leather belt from a nail banged into the bare brick wall. As I breathe in the brick and coal dust, my throat tightens. Then I walk back to Dad, trailing the buckle along the floor behind me, letting it bang and clunk against the furniture. This act of defiance makes him even angrier. I hand the belt over. He tells me to turn round with my back to him and hits me three times across the back of my bare legs. It’s my sister’s turn next. We howl with the unfairness and the pain of it all. We cry as loud as we can, hoping Mum will stop him or the neighbours will hear us and come round and tell him off or have him sent to prison. But no one interferes once you’ve shut the front door of your home. The house next door could be in a different country for all they care.

Dad orders us to our bedroom as extra punishment. It’s always freezing in there. As soon as he’s gone, we root around in the bedside-table drawer, find an old biro and draw around each other’s swollen red welts in blue ink, so even when the marks heal, the squiggly blue outlines will be a record of what he did. We promise each other: we’ll never wash the biro off and we’ll draw over the outlines every day. Our homemade tattoos will be permanent reminders – to him and to us – of what a bully he is. Yep, we’ll show him.

A bit later Dad comes in to see us. We’re sitting on our beds drawing, having got over the worst of the pain and the tears. He cries and hugs us, tells us he’s sorry and asks us to forgive him.

‘Yes, we forgive you, Daddy!’ we chorus.

We have to forgive him, we’ve got to see him every day, life’s going to be even more uncomfortable if we don’t forgive him; it’s a matter of survival. We just want everything to be all right, or seem to be all right. Mum calls out that tea’s ready, Dad tells us to wash off the silly biro and come and sit at the table.

We leave a few blue traces behind on our red skin on purpose, not enough to get him worked up again but enough to salvage our pride, then troop into the tiny steamed-up kitchen to eat stew: lumps on our plates, lumps in our throats, red eyes, red legs. Dad makes a joke and we laugh to please him, then we all chomp away in silence. When no one’s looking, I spit the chewed-up meat into my hand to flush down the toilet later. The radio’s on, the theme tune of

Sing Something Simple

with the Swingle Singers seeps into the room, the vocal harmonies – sweet and sickly – pour out into the air and fill up the silences.

I still can’t stand the sound of those 1950s harmonies – like a drink you got drunk on as a teenager, just the smell of it brings back the nausea

.

6 YOU CAN’T DO THAT

1964

I’m at my babysitter Kristina’s house, my first time in a big girl’s room. There are no dolls or teddy bears anywhere. On her bed is a ‘gonk’, a round red cushion with a long black felt fringe, no mouth, big feet. Her bedspread is purple and she’s painted her furniture purple too. In the middle of the floor is a record player, a neat little box covered in white leatherette, it looks a bit like a vanity case. Flat paper squares with circles cut out of the middle are scattered around the floor. Kristina opens the lid of the record player and takes a shiny liquorice-black disc out of one of the wrappers, puts it onto the central spindle and carefully lowers a plastic arm onto the grooves. There’s a scratching sound. I have no idea what’s going to happen next.

Boys’ voices leap out of the little speaker – ‘Can’t buy me love!’ No warning. No introduction. Straight into the room. It’s the Beatles.

I don’t move a muscle whilst the song plays. I don’t want to miss one second of it. I listen with every fibre of my being. The voices are so alive. I love that they don’t finish the word

love

– they give up on it halfway through and turn it into a grunt. The song careens along, only stopping once for a scream. I know what that scream means:

Wake up! We’ve arrived! We’re changing the world!

I feel as if I’ve jammed my finger into an electricity socket, every part of me is fizzing.

When the song finishes, Kristina turns the record over –

What’s she doing?

– and plays the B-side, ‘You Can’t Do That’.

This song pierces my heart, and I don’t think it will ever heal. John Lennon’s voice is so close, so real, it’s like he’s in the room. He has a normal boy’s voice, no high-falutin’ warbling or smoothed-out, creamy harmonies like the stuff Mum and Dad listen to on the radio. He uses everyday language to tell me, his girlfriend, to stop messing around. I can feel his pain, I can hear it in his raspy voice; he can’t hide it. He seesaws between bravado and vulnerability, trying to act cool but occasionally losing control. And it’s all my fault. It makes me feel so powerful, affecting a boy this way – it’s intoxicating. I ache to tell him,

I’m so sorry I hurt you, John, I’ll never do it again

. I have a funny feeling between my legs, it feels good. I play the song over and over again for an hour until Kristina can’t stand it any more and takes me home.