Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (5 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

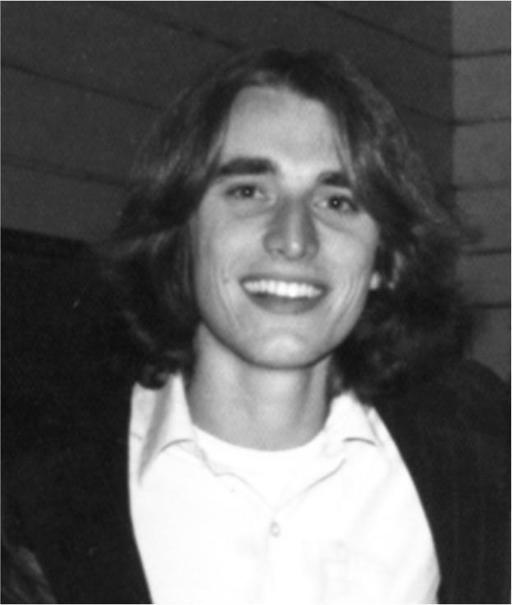

Ben

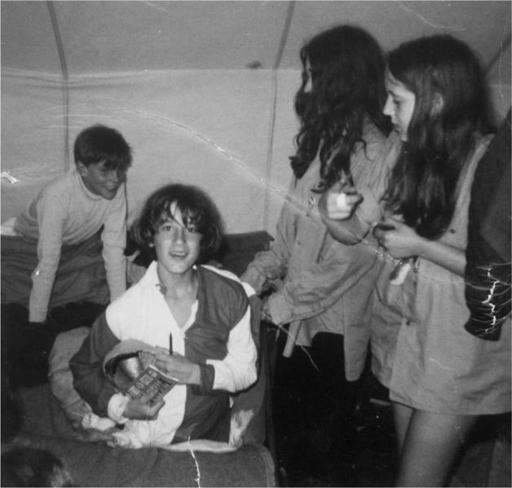

The boy I most fancy after Ben Barson is Nic Boatman, the naughtiest and cutest boy at Woodcraft. Once when me and Nic were kissing and touching each other on a bed in someone’s house, he put his hand inside my knickers and I orgasmed immediately just from the newness of the experience. Well, I think it was an orgasm, it felt like a big twitch and then I wasn’t interested in being touched any more.

Paul, Nic (age fourteen), me (age thirteen) and Maggie in a tent on a Woodcraft camping trip to Yugoslavia, 1968

14 MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC

1967–1972

The music I was exposed to when I was growing up was revolutionary and because I grew up with music that was trying to change the world, that’s what I still expect from it.

I heard most new music through friends and whenever I went out I’d have a record under my arm – not mine, usually I was returning it. The record you carried let everyone know what type of person you were. If it was a rare record, cool people would stop you in the street to talk to you about it. One good thing about not having a phone was that it was difficult for people to remind you to give them their records back, they had to trek round to your house and hope you were in if they wanted it that badly – and then you could always not answer the door. (Mum taught us never to answer the door, the minute the doorbell rang we all froze. If you were near a window, you had to duck under the sill and try not to disturb the curtains. We all knew the drill: wait motionless until the ringing stops and the person goes away. She was worried it would be a social worker. They kept coming round after the divorce.)

Music brought the war in Vietnam right into our bedrooms. Songs we heard from America made us interested in politics; they were history lessons in a palatable, exciting form. We demonstrated against the Vietnam and Korean wars, discussed sexual liberation, censorship and pornography and read books by Timothy Leary, Hubert Selby Jr (

Last Exit to Brooklyn

) and Marshall McLuhan because we’d heard all these people referred to in songs or interviews with musicians. My pin-ups were the political activist and ‘Yippie’ Abbie Hoffman and Che Guevara. Music, politics, literature, art all crossed over and fed into each other. There were some great magazines around too, the sex magazine

Forum, International Times, Spare Rib, Oz, Rave

and

Nova

. Even though we couldn’t afford to travel, we felt connected to other countries because ideas and events from those places reached us through music and magazines.

The first band I ever saw live was the Edgar Broughton Band at the Hampstead Country Club, behind Belsize Park tube station. I sat in the front row on a little wooden chair with a couple of older boys I’d met. I’d never heard live music before and I couldn’t get my ears around it. I didn’t know how to listen to it. Up until then everything I’d heard had been produced, was on a record. There was a speaker right next to my head and all the sounds meshed together, I couldn’t differentiate between them. The band thrashed at their instruments and screamed, ‘

Out demons out!

’ It was deafening.

When I was fourteen I heard there was going to be an anti-war demonstration with famous people giving speeches in Trafalgar Square. It was the thing to go to, as exciting as a rock concert. I hoped there’d be lots of handsome boys there. I spent all Saturday morning before the demo tie-dyeing a white T-shirt black, stirring it round and round with an old wooden spoon in a large aluminium pot on the stove. Mum said, ‘Hurry up, you’ll miss it! Just wear any old thing, it doesn’t matter.’ But I had to look right. The T-shirt came out great, dark grey rather than black, with a white tie-dyed circle in the middle, a bit like the CND peace sign. I sewed black fringes down the sides of my black cord jeans and washed my hair by kneeling over the bath, drying it in front of the open oven with my head upside down so it would look full and wild. Then off me and my friend Judie went to the demo, chanting, ‘Hey hey, LBJ, how many kids have you killed today?’ at the top of our voices. We got off the bus and ran down Haymarket towards Trafalgar Square. When we got there it was completely deserted. The paving stones were covered in litter, empty bottles rolled around, leaflets were blowing in the wind. No people, just pigeons. We’d been so long messing around with our clothes that we’d missed the whole thing. We were only disappointed for a minute, then we jumped in one of the fountains and chased each other around. A policeman told us off, said if we didn’t stop he’d arrest us and tell our parents. We were scared of going to prison, so we ran off to the bus stop. Sitting on the top deck of the bus, the fringes on my jeans all straggly, my hair damp and flat and the dye from my wet T-shirt leaving grey streaks across my arms, I thought,

What a great day!

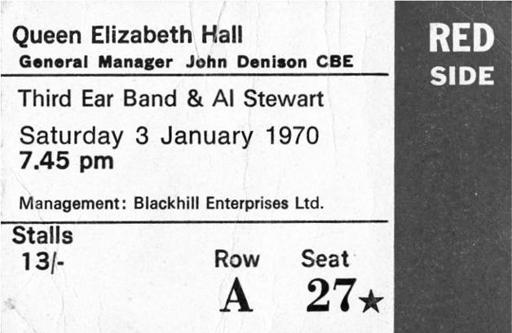

One of the strangest bands I saw around this time was Third Ear Band at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. I found out about them through listening to John Peel on the radio, he was always mentioning them. He played on their record

Alchemy

. The music was over my head, really difficult, but I understood the ideas – experimentation, pushing boundaries and not conforming to musical clichés. I stared at the stage, I couldn’t tell if one of the players in the band was male or female, the tall skinny one with long black hair; I stared and stared at this one hoping and hoping that they were female. I left without knowing as she or he had their head down the whole time.

Me and my friend Zaza went to see Third Ear Band again (even though they were very experimental, they played all over the place and had a big following) in July 1969 when I was fifteen. They opened for the Rolling Stones at the ‘Stones in the Park’ free concert in ‘the cockpit’ – the big dip in the grass in Hyde Park. King Crimson were on too.

Zaza was a year older than me and insane about music. She was strikingly beautiful, natural, never wore makeup (nor did I), long shiny black hair, always wore clean jeans and a cool T-shirt, never

ever

a skirt. For the concert I wore a long, pale lemon lace dress from the 1930s, it fitted like it was made for me. It was completely see-through and I wore a short mauve slip under it. I loved that the hem trailed in the dirt so it was muddy and frayed. As usual I had bare feet. Zaza and I couldn’t get near the stage, so we sat down on the grass towards the back. The atmosphere was laden with sadness because Brian Jones, the Stones’ guitarist, had died in a swimming pool two days before. He’d recently been chucked out of the Stones and replaced by Mick Taylor – it felt like they replaced god: how could they do that? Me and Zaza thought Brian probably committed suicide because he was so upset. We wondered how the Stones were going to handle the whole thing, if they’d ignore it or if they even cared that he was dead. Everyone around us was talking about it:

Do the rest of the Stones feel guilty? How does Mick Taylor feel? Will he appear?

Mick Jagger drifted onto the stage wearing a diaphanous white dress with floaty bell sleeves over white flared trousers. The dress said it all.

We are the Stones. We’re shocking but we’re also caring and gentle. We will honour and acknowledge Brian’s life and death, but in our own way. Black mourning clothes are for straights

. Mick read a poem and then released thousands of white butterflies over the crowd, they fluttered over our heads into the park. We were part of a big moment in history and we knew it. It was like we were at Brian Jones’s funeral; the Stones shared this moment with us. During one song, Jagger strutted to the front of the stage and the girls in the front row reached out to touch him. He grabbed Mick Taylor and pulled him to the front, making Taylor sit down beside him on the edge of the stage, and gestured to the girls to touch the guitarist too. Taylor looked mortified, he hung his head down and just kept playing. I felt a terrible pain on the top of my foot, in between my toes. Someone was stubbing a cigarette out on it, we were so tightly packed together he didn’t realise. It didn’t matter. When the show was finished, me and Zaza walked back through the park, trying to avoid squashing the dying butterflies under our feet. There were so many of them.

Another great free concert was when Fleetwood Mac played an all-nighter on Parliament Hill Fields. My friend Hilary and I climbed out of the bedroom window of her mum’s flat in Highgate at 10 p.m. and walked along Southwood Lane then up Highgate Hill, across the fields, towards the corrugated-iron bandstand. Loads of like-minded people were walking along the roads even though it was so late. We felt special that it was happening in our area; we knew Highgate and the Heath back to front. More and more people arrived, hundreds of us. We got talking to two nice boys and hung out with them all evening. Fleetwood Mac came on at midnight. They played

Albatross

; it was like being in an open-air church, the sad guitar crying out over the black trees … we lay on our backs and stared up at the sky, transported away from North London by this haunting, elevating music. It was the most magical experience I’d ever had.

Fleetwood Mac only played a couple of songs before the atmosphere was ruined by skinheads running down the hill and throwing things. The concert was stopped, so we went home. The two nice boys walked with us. Me and Hilary played knock down ginger, ringing the doorbells of the fancy white houses and then running away. The boys, who were a bit older than us, weren’t so keen. As we all charged down the hill, ‘my one’ held his hair down as he ran. Completely turned me off. Couldn’t wait to get rid of him after that.

Marc Bolan was the most important man in my life for a year. I think what appealed to me most was his prettiness. He was sexual – pouting and licking and throwing his hips forwards – but he wasn’t at all threatening to young girls. It was a new thing for men to be so delicate and pretty and overtly sexual at the same time. Marc was almost a girl. He wore girls’ tap shoes from the dance shop Anello and Davide in pretty colours, had long ringletty hair, glitter around his eyes and a cupid’s bow mouth: you could almost be him. He wasn’t scary to fantasise about, you could be dominant or dominate him, he wasn’t the kind of guy who would jump on you or hurt you. Fantasising about Marc Bolan (or any pop star) was a great way to discover your sexuality, a safe way in.

Listening to T. Rex was one of the first times I actually noticed guitar playing (apart from Peter Green and George Harrison). Bolan’s riffs were so catchy and cartoony – combined with a very distinctive guitar sound – that I would find myself singing the parts. Girls didn’t usually listen out for guitar solos and riffs, that was a male thing –

wow that was so fast, wow that was a really obscure scale, wow the way he bends the notes

. I used to listen to the lyrics and the melody of songs, not dissect the instruments. I couldn’t bear Hendrix’s playing at the time, it was so in your face and he was so overtly sexual, it was intimidating. I remember saying to my cousin Richard, ‘The only words I can make out in this song are “’Scuse me while I kiss the sky.”’ He said, ‘I don’t even know that many.’ He was a huge Hendrix fan and he didn’t know one word of any of his songs.