City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (41 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

*

Nothing would have confirmed Petrarch’s view of Venetians’ material obsessions so much as the journey of Giosafat Barbaro,

a merchant and diplomat who set out from Tana with 120 labourers to search a Scythian burial mound on the steppes for treasure. In 1447 he travelled by sledge up the frozen rivers, but ‘found the ground so hard we were constrained to forgo our enterprise’. Returning the following year, the workmen dug a deep cutting into the artificial hill. They were disappointed to find only a great depth of millet husks, carp scales and some fragmentary artefacts: ‘beads as big as oranges made of brick and covered with glass … and half of a handle of a little ewer of silver with an adder’s head on top’. They were again defeated by the weather. Barbaro’s men had dug into a rubbish tip. They had missed by a few hundred yards the burial chamber of a Scythian princess, adorned with enough jewellery to ignite all their wildest Venetian dreams of oriental gold. It was not discovered until 1988.

City of Neptune

THE VIEW FROM 1500

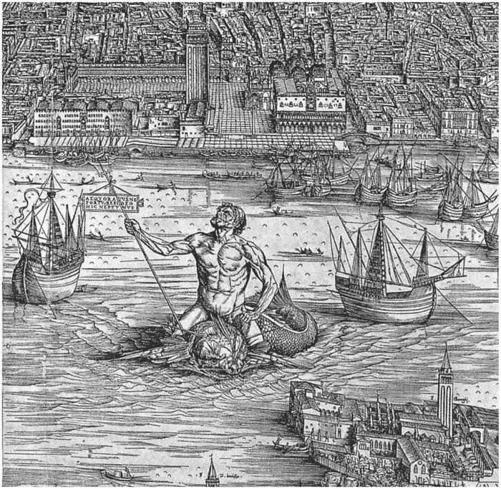

In 1500, an exact half-millennium after Doge Orseolo embarked on his voyage of conquest, the Venetian artist Jacopo de’ Barbari published an immense and spectacular map, almost three metres long. The angle of vision is giddily tilted to present a bird’s-eye view of Venice impossible to human perspective before the invention of flight. From a thousand feet up, Barbari calmly laid out the city in huge and naturalistic detail. The woodcut panorama was based on careful surveys conducted from the city’s campaniles. It shows everything: the churches, squares and waterways, the doge’s palace, St Mark’s and the Rialto, the customs house and the German

fondaco

, and the lazy S-shaped meander of the Grand Canal spanned at its centre by the one wooden bridge.

Despite the level of detail, the map is not quite a factual record. De’ Barbari tweaked the perspective to emphasise the marine appearance of the place, so that it looks like an open-mouthed dolphin with its distinctive fish tail at the eastern end. Like the visual propaganda of the city – its buildings and banners, its elaborate rituals, feast days and festivals – the map is a work of profound intention. De’ Barbari’s Venice is a city of ships, a celebration of maritime prosperity. On the auspicious anniversary it trumpets the glorious ascent from muddy swamp to the richest place on earth. The city appears immortal, as if abstracted from the erosions of time. There are almost no people visible, none of the hubbub and jostle of trade. It displays wealth without human effort.

The lagoon itself is tranquil, just lightly stirred by benign winds blown by the breath of cherubs to speed the fleets on their

prosperous way. Tubby sailing ships, fat as jugs, ride at anchor on taut hawsers in all states of readiness: some are fully rigged, some are demasted, others are chocked up in dry dock or tilted on their sides; aerodynamic galleys, raked back and low, lie beside them; on the

Bucintoro

, symbol of the marriage with the sea, the figure of Justice stands, sword in hand, erect in the prow; a merchant ship is being towed up the Grand Canal. Around the ocean-going craft, a host of little vessels skim the woodcut ripples. All the permutations of Venetian rowing styles are on show: a regatta of four-man racing craft; the flat-bottomed lagoon skiffs rowed by two men; gondolas poled by one; small sailing boats like beaked Phoenician traders laden with produce from the vegetable gardens of the lagoon. The mainland has been pushed back, as if irrelevant.

The map is presided over by benign gods. At the top, the tutelary deity of Venice is Mercury, god of trade, proclaiming with a semicircular sweep of his hand the message, ‘I, Mercury, shine down favourably on this above all other places of commerce’; underneath the portentous date: 1500. But it is Neptune who really catches the eye at the centre of the map. The powerful muscled figure rides a scaly and snouted dolphin; from his trident, held aloft to the skies, the message proclaims: ‘I, Neptune, reside here, watching over seas and this port.’ It is a triumphant statement of maritime power. In de’ Barbari’s image the city is at its peak.

City of Neptune

The ships so carefully portrayed, whose number the pilgrim Pietro Casola was unable to count, were Venice’s life blood. Everything that the city bought, sold, built, ate or made, came on a ship – the fish and the salt, the marble, the weapons, the oak palings, the looted relics and the old gold; de’ Barbari’s woodblocks and Bellini’s paint; the ore to be forged into anchors and nails, the Istrian stone for the palaces of the Grand Canal, the fruit, the wheat, the meat, the timber for oars and the hemp for rope; visiting merchants, pilgrims, emperors, popes and plagues. No state in the world occupied itself so obsessively with managing the business of the sea. A sizeable proportion of the male

population earned their living there; all ranks and classes participated, from the noble shipowners down to the humblest oarsman. When the doge Tommaso Mocenigo gave his deathbed oration in 1423 he counted up the Republic’s maritime resources, albeit with some element of exaggeration: ‘In this city there are three thousand vessels of smaller burden, which carry seventeen thousand seamen; three hundred large ships, carrying eight thousand seamen; five-and-forty galleys constantly in commission for the protection of commerce, which employ eleven thousand seamen, three thousand carpenters, three thousand caulkers.’

*

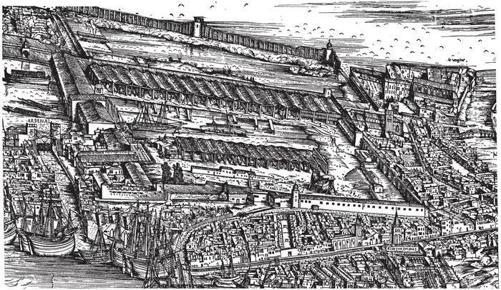

In de’ Barbari’s map the single most prominent structure is the immense walled enclosure of the state arsenal at the tail of the

dolphin. It had grown in size continuously over three hundred years with the maritime requirements of the Republic. By 1500 the sixty-acre site, enclosed by blind fifty-foot-high brick walls topped with battlements, comprised the largest industrial complex in the world. It was capable of building, arming, provisioning and launching eighty galleys at a speed and a level of consistency unmatched by any rival. The ‘Forge of War’ manufactured all the maritime apparatus of the Venetian state. It provided dry and wet docks, hangars for building and storing galleys, carpenters’ workshops, rope and sail factories, forges, gunpowder mills, lumber yards, and storehouses for every component of the process and the associated equipment.

The arsenal

By continuous refinement the Venetians had evolved something as close to assembly-line production as was possible given the organisational resources of a medieval state. The key concepts were specialism and quality control. Skill separation was critical, from the woodmen growing and selecting trees in distant forests, through the master shipwrights, sawyers, carpenters, caulkers, smiths, rope weavers and sail makers down to the general labourers who carried and fetched. Each team’s work was the subject of rigorous inspection. Venice knew well that the sea was

an unforgiving judge, gnawing iron, rotting cables, testing seams, shredding sailcloth and rigging. Strict regulations were in place governing the quality of materials. The bobbin of each hemp spinner was marked so that the work could be individually identified; every rope that emerged from the ropewalk was tagged with a coloured label, indicating the use to which it could reliably be put. The care with which the Signoria oversaw each stage of production was a reflection of its understanding of the marine life. A ship, its crew and thousands of ducats of valuable merchandise could founder on shoddy work. For all the mythological rhetoric, Venice rested on profoundly material facts. It was a republic of wood, iron, rope, sails, rudders and oars. ‘The manufacture of cordage’, it was declared, ‘is the security of our galleys and ships and similarly of our sailors and capital.’ The state made unconditional demands; its caulkers should be accountable for split seams, its carpenters for snapped masts. Poor work was punishable with dismissal.

The arsenal was physically and psychologically central to Venice. Everyone was reminded of ‘the House of Work’ on a daily basis by the ringing of the

marangona

, the carpenter’s bell, from the campanile in St Mark’s Square to set the start and end of the working day. Its workers, the

arsenalotti

, were aristocrats among working men. They enjoyed special privileges and a direct relationship with the centres of power. They were supervised by a team of elected nobility and had the right to carry each new doge around the piazza on their shoulders; they had their own place in state processions; when the admiral of the arsenal died, his body was borne into St Mark’s by the chief foremen and twice raised in the air, once to betoken his acceptance of his responsibilities and again his fulfilling of them. The master shipwrights, whose skills and secret knowledge were often handed down through the generations, were jealously guarded possessions of the Venetian state.

The arsenal lent to the city an image of steely resolve and martial fury. The blank battlements that shut out the world were

patrolled at night by watchmen who called to each other every hour; over its intimidating gateway the lion of St Mark never had an open book proclaiming peace. It was firmly closed: the arsenal lion was ready for war. The industry of the place amazed visitors. When Pietro Casola came in 1494 he saw in the munitions store ‘covered and uncovered cuirasses, swords, crossbows, large and small arrows, headpieces, arquebuses, and other artillery’; in each of the large sheds used for galley storage there were twenty compartments, holding

… one galley only, but a large one, in each compartment; in one part of the arsenal there was a great crowd of masters and workmen who do nothing but build galleys or other ships of every kind … there are also masters continually occupied in making crossbows, bows and large and small arrows … in one covered place there are twelve masters each one with his workmen and his forge apart; and they labour continually making anchors and every kind of iron-work … then there is a large and spacious room where there are many women who do nothing but make sails … [and] a beautiful contrivance for lifting any large galley or other ship out of the water.

And he saw the Tana, the rope-making factory, a narrow hall a thousand feet long, ‘so long that I could hardly see from one end to the other’.

The arsenal worked on a just-in-time basis; it dry-stored all the components of galley construction in kit form for rapid assembly in times of war. Orderly arrangement was critical. To despatch a fleet of war galleys at short notice, the arsenal might be holding five thousand rowing benches and footbraces, five thousand oars, three hundred sails, a hundred masts and rudders, rigging, pitch, anchors, weapons, gunpowder and everything else required for quick deployment. The Spanish traveller Pero Tafur saw the fitting-out of a squadron of galleys in double-quick time during the summer of 1436: one by one hulls were launched into the basin where teams of carpenters fitted the rudders and masts. Tafur then watched as each galley passed down an assembly line channel:

… on one side are windows opening out of the houses of the arsenal, and the same on the other side, and out came a galley towed by a boat, and from the windows they handed out of them, from one the cordage, from another the bread, from another the arms, and from another the ballistas and mortars, and so from all sides everything which was required, and when the galley had reached the end of the street all the men required were on board, together with the complement of oars, and she was equipped from end to end. In this manner there came out ten galleys, fully armed, between the hours of three and nine.