City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (44 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

In between, the passengers saw all the wonders and perils of the deep pass them by. Casola watched a water spout ‘like a great beam’ suck a mass of water out of the sea, and the aftermath of an earthquake in Candia, dashing the ships together in the harbour ‘as if they would all be broken to pieces’, and churning the sea to a strange colour; he passed Santorini, whose bay was thought to be bottomless, where the captain had once witnessed a volcanic explosion and seen a new island ‘black as coal’ rise spontaneously from the depths. Fabri’s ship was all but sucked down by a whirlpool off Corfu, got mistaken for Turkish pirates off the coast of Rhodes and narrowly dodged a Turkish invasion fleet bound for Italy. And in the midst of this, through calm and storm, seasickness

and fear of corsairs, there was landfall in the ports of the Stato da Mar, welcome relief from the interminable rocking of the ship, and a promise of food and fresh water.

The pilgrims had full opportunity to glimpse how hard the marine life was. They watched the intense labours of the

galeotti

, working to the whistle, doing everything at a run and with loud shouts, ‘for they never work without shouting’. Passengers learned to keep out of their way or risk being knocked overboard as the seamen lugged up anchors, lowered and raised sails, scurried up rigging, swayed from the tops, sweated on the oars to manoeuvre the ship against the wind into a secure harbour. They swore ‘Spanish oaths’, terrible enough to shock the pious pilgrims, suffered cold and heat and the endless delays of contrary winds and lived for moments of respite – landfall or a barrel of wine. All seamen were prey to superstition; they disliked holy water from the River Jordan on their ships and stolen holy relics and Egyptian mummies; drowned bodies were an ill omen; corpses in the hold were sure to bring disaster – all misfortunes of a voyage could be attributed to such events. They called on a galaxy of special saints to ease their passage and had their prayers said in Italian rather than Latin. When the winter sea became furious off the coast of Greece, it was the archangel Michael beating his wings; in the rough weather of late November and early December they called on St Barbara and St Cecilia, St Clement and St Katherine and St Andrew; St Nicholas was invoked on 6 December, then the Virgin herself two days later; they were wary of mermaids, whose singing was fatal, though these might possibly be distracted with empty bottles thrown into the sea, with which the mermaids liked to play. And in every port they brought out small quantities of merchandise from chests and sacks to try their luck.

Fabri sat on deck by day and night in good weather and bad, following the intricate life of the ship. He compared it to being in a monastery. In Candia he watched underwater repairs to the rudder:

… the waterman stripped to his drawers, and then taking with him a hammer, nails and pincers, let himself down into the sea, sank down to where the rudder was broken, and there worked under water, pulling out nails and knocking in others. After a long time, when he had put everything right, he reappeared from the depths, and climbed up the side of the galley where we stood. This we saw; but how that workman could breathe under water, and how he could remain so long in the salt water, I cannot understand.

He had explained to him navigation by portolan maps and observed at close quarters how the pilot read the weather ‘in the colour of the sea, in the flocking together and movement of the dolphins and flying fish, in the smoke of the fire, the smell of bilge water, the glittering of ropes and cables at night, and the flashing of oars as they dip into the sea’. In the dark he frequently escaped the foetid pilgrim dormitory to sit upon the woodwork at the sides of the galley, letting his feet hang down towards the sea, and holding on by the shrouds. If there were the perils of storm and calm, there were also times of exhilaration and beauty when the sea would be like rippled silk, the moon bright on the water, the navigator watching the stars and the compass,

… and a lamp always burns beside it at night … one always gazes at the compass, and chants a kind of sweet song … the ship runs along quietly, without faltering … and all is still, save only he who watches the compass and he who holds the handle of the rudder, for these by way of returning thanks … continually greet the breeze, praise God, the blessed Virgin and the saints, one answering the other, and are never silent as long as the wind is fair.

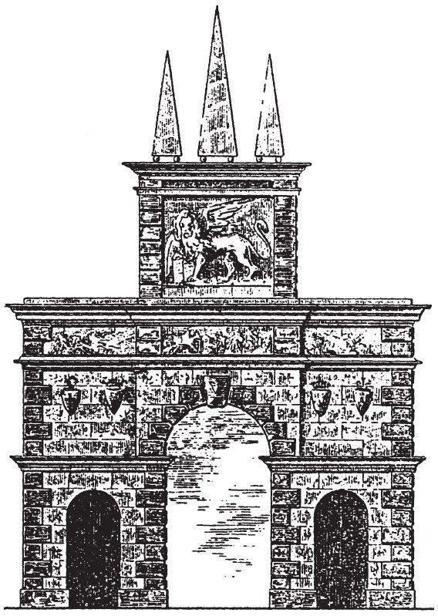

Fabri and Casola were able to make almost the entire voyage to Jaffa by way of Venetian ports. All down the Dalmatian coast, round Coron and Modon, via Crete and Cyprus they put in at harbours where the flag of St Mark fluttered in the salt wind. They witnessed the majestic operation of the Stato da Mar at first hand. They observed the prowling menace of its war fleets, its state ceremonies, colonial dignitaries, banners and trumpet calls. They saw the tangible fruits of the sea stacked high in Venetian

warehouses. To outsiders, the city projected in de’ Barbari’s map seemed the pinnacle of prosperity. But this was the last generation of pilgrims to sail so freely. Even as Neptune’s trident was raised triumphantly aloft, the Stato da Mar was simultaneously in hidden decline. For seventy years shadows had been creeping over a sunlit sea. There were social factors at work – the toughness of the maritime life was one – and the Venetian lion now had his paws firmly planted on dry land; the business of the terra firma was starting increasingly to consume the Republic’s resources. But above all it was the inexorable advance of the Ottoman Empire which threatened to dissolve Venice’s marriage with the sea at the moment of its supremacy.

PART III

ECLIPSE: THE RISING MOON

1400–1503

The Glass Ball

1400–1453

On 1 June 1416, the Venetians engaged an Ottoman fleet at sea for the first time. The captain-general, Pietro Loredan, had been sent to the Ottoman port at Gallipoli to discuss a recent raid on Negroponte. What happened next he related in a letter to the doge and the Signoria.

It was dawn. As he approached the harbour, a signal to parley was misinterpreted as a hostile attack. The lead ships were met with a hail of arrows. In a short time the encounter had turned into a full-scale battle.

As captain I vigorously engaged the first galley, mounting a furious attack. It put up a very stout defence as it was well manned by brave Turks who fought like dragons. But thanks to God I overcame it and cut many of the Turks to pieces. It was a tough and fierce fight, because the other galleys closed on my port bow and they fired many arrows at me. I certainly felt them. I was struck on the left cheek below my eye by one which pierced my cheek and nose. Another hit my left hand and passed clean through it … but by fierce combat, I forced these other galleys to withdraw, took the first galley and raised my flag on her. Then turning swiftly about … I rammed a galleot with the spur [of my galley], cut down many Turks, defeated her, put some of my men aboard and hoisted my flag.

The Turks put up incredibly fierce resistance because all their [ships] were well manned by the flower of Turkish sailors. But by the grace of God and the intervention of St Mark we put the whole fleet to flight. A great number of men jumped into the sea. The battle lasted from morning to the second hour. We took six of their galleys with all their crews, and nine galleots. All the Turks on board were put to the sword, amongst them their commander … all his nephews and many other important captains …

After the battle we sailed past Gallipoli and showered those on land with arrows and other missiles, taunting them to come out and fight … but none had the courage. Seeing this … I drew a mile off Gallipoli so that our wounded could get medical attention and refresh themselves.

The aftermath was similarly brutal. Retiring fifty miles down the coast to Tenedos, Loredan proceeded to put to death all the other nationals aboard the Ottoman ships as an exemplary warning. ‘Among the captives’, Loredan wrote, ‘was Giorgio Callergis, a rebel against the Signoria, and badly wounded. I had the honour to hack him to pieces on my own poop deck. This punishment will be a warning to other bad Christians not to dare to take service with the infidel.’ Many others were impaled. ‘It was a horrible sight,’ wrote the Byzantine historian Ducas, ‘all along the shore, like bunches of grapes, sinister stakes from which hung corpses.’ Those who had been compelled to the ships were freed.

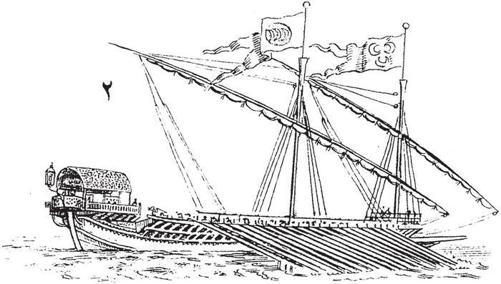

An Ottoman galley

In this first hostile engagement, Loredan had almost completely destroyed the Ottoman fleet – and the means quickly to recreate it. The Venetians understood exactly where the source of Ottoman naval power lay. Many of the nominal Turks in their

fleet were Christian corsairs, sailors and pilots – maritime experts without whom the sultan’s embryonic navy was unable to function. The Republic’s policy was to remain unbending in this respect: snuff out the supply of skilled manpower and the Ottomans’ naval capability would wither. It was for this reason that they butchered the sailors so mercilessly. ‘We can now say that the Turk’s power in this part of sea has been destroyed for a very long time,’ wrote Loredan. No substantial Ottoman fleet would put to sea again for fifty years.

The accidental battle of Gallipoli bred a certain over-confidence in Venetian sea power. For decades after, galley commanders reckoned that ‘four or five of their galleys are needed to match one of ours’. Touchy about their Christian credentials, they also used the victory to point out to the potentates of southern Europe their reputation as ‘the only pillar and the hope for Christians against the Infidels’.

*

The Ottomans had advanced so swiftly and silently across Asia Minor in the chaotic aftermath of the Fourth Crusade that their progress had passed, for a time, almost unnoticed. They had inserted themselves into the Byzantine civil wars and the trade contests of the Venetians and the Genoese. They were alive to the opportunities of confusion, siding with the Genoese in the 1350s, who shipped them across the Dardanelles to Gallipoli, from which they could not be dislodged. Picking up speed, they struck into Bulgaria and Thrace, surrounded Constantinople and reduced the emperors to vassals. By 1410 Ducas claimed that there were more Turks settled in Europe than in Asia Minor. It was as if the column in the Hippodrome had grown a fourth serpent, whose python-like grasp threatened slowly to squeeze all its rivals to death. Christian Europe, torn by conflicting interests and religious schisms, failed to respond. Successive popes, increasingly aware of the danger of ‘the Turk’, wrung their hands at the enmity between Catholic and Orthodox, and the endless Venetian–Genoese wars; without the naval resources of the

maritime republics crusades died at birth in the antechambers of the Vatican.

Venice was watchful of this burgeoning power. By the 1340s they were warning of ‘the growing maritime power of the Turks. The Turks have, in effect, ruined the islands of Romania [the Aegean] and as there are hardly any other Christians to combat them, they are creating an important fleet with a view to attacking Crete.’ The power vacuum which Venice had helped to create in 1204 was now being filled. It was the Republic’s policy never to make military alliances with the Ottomans, as the Genoese did, but neither were they in a position to act against them. Always distracted by other wars and by trading interests, and wary of unstable crusading alliances which could leave them dangerously exposed, they watched and waited. They observed sceptically from the sidelines an ill-fated crusade against the Ottomans by a joint French and Hungarian force in 1396; their sole contribution was a measure of naval support, picking up a pathetically small huddle of survivors from the shores of the Danube after its total defeat at the battle of Nicopolis. Their response to appeals to defend Christendom was stock: they were not prepared to act alone, but whenever they surveyed the idealistic crusading projects of the papacy they politely declined.