Chernobyl Strawberries (9 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

The army bus is full of handsome, jovial men in fine uniforms. When it stops on the corner, its doors often release a stream of laughter, through which my father walks towards us. It is quite unlike the long snake of the city bus, full to bursting with angry people holding tight twenty or thirty to each pole. My mother parts the crowd with sweet apologies, like Moses crossing the Red Sea.

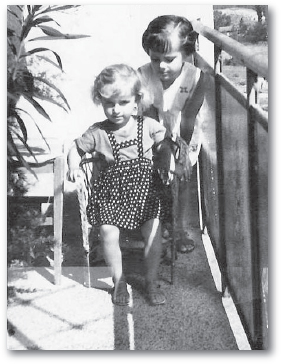

My younger sister and I

From ten minutes to four onwards, my sister and I keep watch for their return, looking up and down the road like spectators at a tennis match. When we notice the small silhouettes of Mother and Grandmother at the opposite ends of the street,

we run to help carry their loads: a mattock and bags of vegetables for Grandmother, who comes from the bottom of the hill; carrier bags for Mother, who comes from the bus station at the top. If my father is the first to emerge, we simply jump on him, clinging like limpets to each arm, and let him carry us into the house. This ritual is repeated until some point just before my twelfth birthday, when my mother takes me aside and tells me that such unladylike actions no longer befit me. After that, only my sister jumps, hanging off my father's right arm like a baby monkey, for two more years. I walk beside them.

The women in my family are tiny â my mother five foot two, my grandmother barely five foot. Returning from work, they sometimes round the corner at the same time: Mother click-clacking in her high heels, Grandmother slowly dragging her lame foot in the thick woollen socks and flat rubber shoes she wears in the field. Both women take enormous pride in their appearance: the younger in looking as elegant as possible in her tailored suits, the older in appearing as impoverished as possible in her widow's black, with a black pinafore apron and a black scarf. When she takes her scarf off, Grandmother's face is divided into spheres of dark and pale skin, like a diagram of the crescent moon.

If a neighbour stops to greet her, usually saying something along the lines of âWhy are you working so hard at your age? Why don't you take a rest and let the children look after you?' Granny sighs and responds, âHow can I? There is an entire family to feed.' Mother gets quite upset if she hears this. Supporting your elders is a matter of pride and yet â like that aunt of Proust's who would never own up to nodding off â my grandmother is absolutely unwilling to admit to being supported.

Even when they are not carrying anything, we run towards them, trailed by the barking from the neighbourhood dogs, who run along the length of each garden as we pass, in a doggy relay race. Grandmother greets us with a line of criticisms and complaints (âYou take so long, you lazy children. I'm so tired. I'm so thirsty. Why do I have to work for you?'), my mother with a hug and a smile, but we know that they are equally pleased to see us. Once Mother's back, the Arcadian atmosphere of our day is replaced by mayhem for three or four hours. She prepares our meals, dusts and cleans and washes, makes things for the deep-freeze and things for the larder, and compiles the ledgers of household bills. When all of this is done, she watches television, reads or knits. Rarely but quite regularly, she disappears to cry in the darkness of one of the bedrooms. She does so noiselessly, without sobbing. You wouldn't know that she was crying unless you asked. We don't ask. We know that if we did she'd cry even more. After a while she washes her face and comes back to us.

When she was eighteen, my mother came to Belgrade from a village in eastern Serbia to study French and Arabic at the university. Her father wanted her to become a journalist and, when he picked her up from the train station in his horse-drawn carriage, they often spoke of the distant places she was going to report from one day. Mother was from a wealthy restaurateur's family which once had lots of land and several houses arranged around a shady central courtyard full of dahlias and sweet peas. They had plum, apple, and peach and apricot orchards; a large vineyard on one of the best slopes in the village; a pepper and aubergine nursery dissected by a grid of small canals with streams of clean water; and a

bostan

â a field set aside for orange, green and yellow melons, and huge

emerald balloons of watermelons on a necklace of leaves trailing on dry, fragrant soil. Mother told me how sometimes, in the evening, they used to throw the largest watermelons into the lake at the bottom of the field, and let them cool through the night, bobbing on the translucent surface of the water. They were ready to be picked up during the following morning's swim.

My mother's father

After a year in Belgrade, Mother had to return home to eastern Serbia. Her father and grandfather were both in prison for failing to deliver an impossible quota of grain to the state. At the same time, land was being taken away in order to create large state farms in the process known as collectivization,

through which the peasants became state employees. My grandfather was ill-suited to becoming anyone's employee. He had already been jailed in the Second World War and was now on a big-time collision course with the socialist state. My earliest memory of him is of hearing the vilest of curses directed at the TV screen on which President Tito walked proudly, arm in arm with some African leader whose people's liberation struggle my country was generously supporting.

Grandfather returned from prison with raging tuberculosis and something that my mother always referred to as âopen caverns', bleeding wounds inside his chest. Paradoxically, by the time he was released the government's policy had changed and the plan to put all land under state control was abandoned, but the family was never the same. Their restaurant was requisitioned as warehouse space and the land â with low purchase prices and high delivery quotas enforced by the state â was insufficient to keep the family going. Their horses were sold off, their coaches rotted away in empty barns. They were hungry amid some of the most fertile fields in Europe.

I remember childhood visits to my maternal home, when I roller-skated through the vast dining hall. The derelict kitchens still smelled of smoked meat, the ice house echoed emptily. I made complicated figures around ornate pillars and through swinging doors, bathed in the jelly-bean spectrum of light which came through tall glass panels inscribed with my mother's maiden name.

By the time she returned to Belgrade to continue her studies, she had switched to law, a subject she never much liked. She had to support herself and law promised a securer future. She got a job as a night-shift duty clerk with City Transport and stayed there for forty years. You used to, apparently, in those days: stay in the same job, in the same town, in the same country, with the same man, your entire adult life. You

had to choose very carefully, and make your choices before you were twenty-five, after which the options narrowed dramatically. The dream of bylines from foreign shores was passed on to me.

During those summers I spent in my mother's village, I grew easily bored with the open fields and the relentless sun. I hid with a book in a guest room full of dark furniture and fading photographs of long-forgotten weddings and christenings. I remembered the room being used only once, when I was seven. The family gathered around the open coffin in which my maternal grandmother lay, aged fifty-two, her arms carefully folded across her chest. A few weeks before she died, she had taken me to one side and asked me not to cry at her funeral but to sing instead. I respected her wish. Although it felt unbearably sad, sadder even than crying, I sat in the corner of the big room, quietly singing a nursery rhyme, until Mother ordered me to stop. She had never ordered me to do anything before, which is one of the many reasons I remember the day so vividly. The table on which Granny's body rested in a luminous circle of candles was now laden with fragrant yellow quinces.

I searched through my maternal grandmother's vast dowry chests, looking for God knows what amid the layers of starched linen with fading embroidery. At the bottom of one drawer, under the lining of greaseproof paper, I found my mother's French exercise book. I leafed through pages and pages of neatly copied, carefully accented text. â

Je suis heureuse. Tu es heureux

,' said the last line, dated December 1949. The exercise in grammar suddenly seemed very personal. I returned the notebook to its resting place. I wanted to know whether Mother was really happy when she wrote this, but there was no way of telling.