Chernobyl Strawberries (8 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

Housed in a cluster of seventies buildings, the university is more like a piece of the homeland I left behind than anything still remaining in it. Remove the student union shop, empty the car park, add a few tramlines below and a mesh of trolleybus wires above, and you could be back at Belgrade City Transport thirty years ago. Walking towards the lecture theatres on crisp mornings, when the Thames, hidden behind neat rows of Edwardian villas, smells of rot and clay, I sometimes feel I am becoming my mother. My pace shortens and accelerates,

my arms no longer wave about, I tread as elegantly as I can in my cowboy boots, and when I sit down I keep my hands in my lap and my back upright. I say no thank you and yes please. I smile. My eyes are blue.

My mother's office is full of supplicants â members of her staff asking for a swap on the work rota or a day off for a spurious funeral, pensioners complaining about the slow issue of travel-cards, foreign students with vouchers gone astray. The room is full of cigarette smoke. (My mother doesn't smoke, but practically all of the men and quite a few of the women who work for City Transport are chain-smokers.) A picture on the wall shows Comrade Tito, the Yugoslav President, inside a brand-new trolleybus. He wears the grey uniform of a marshal of the Yugoslav National Army, with more buttons on it than on the dashboard he is leaning against. Below Tito's picture is a large street map of Belgrade, with a spider's web of bus routes in blue, trolleybus routes in green and tram routes in red. My mother knows each of these by heart. At home, we sometimes play a game which consists of asking her questions about imaginary itineraries â what is the best route, for example, from Patrice Lumumba Street in Karaburma to the International Brigades Avenue in New Belgrade, on the other side of town â and she reels off line numbers, interchanges and frequencies. It is a game my mother loves.

Her office houses two large desks with telephones and typewriters, a couple of heavy leather armchairs and a small table with a ficus plant and an overflowing ashtray. When a visitor comes, Mother telephones for small cups of bitter coffee from the canteen in the basement. Anyone important is announced by a security officer, a large woman called Stanka, who wears a black leather jacket and short boots which end just

below her melon-like calves and look as though they were designed by NASA for Mars landings. Under her jacket, Stanka has a wide belt with a pistol in a fine leather holster. She is a gregarious woman. She often laughs loudly and her belly moves up and down. Her pockets are full of boiled sweets, which she hands out to my sister and me when we visit.

My mother never forgets to ask Stanka about the health of her only child, Stanko, a little boy whose legs are thin and spindly, like cooked spaghetti. The security officer is the only single mother we know in the whole of Belgrade, and we feel sorry for her little son, as though he were an orphan, or worse. We cannot begin to imagine what his sad, fatherless life must be like. Stanka often repeats that Stanko is the only man in the entire world she would cook and wash for. âMen, they are all the same,' she laughs, and puts her big hand over the pistol holster. âThey all deserve to rot in hell.' My mother doesn't laugh. âOff to work, woman. Off to work,' she says, and gives Stanka a pat on the back with her small hand, a large amethyst and gold ring glinting against the heavy leather jacket. Stanka seems almost a foot taller than my mother.

There are three telephones on my mother's desk. They ring all the time and she often speaks on two lines simultaneously. My mother's secretary, a middle-aged white-haired man called Toma, without the index finger on his right hand (a hunting accident), comes in and out of the room carrying bits of paper for my mother to sign. (I can't remember whether the absence of a digit affected Toma's touch-typing speed.) Many of the supplicants assume that Toma is the boss â communism notwithstanding, Yugoslavia is still a patriarchal place â and start repeating their stories of misfortune when he enters. When Toma points out the error of their ways, they return to my mother with a syrupy flow of apologies.

I sit in one of the armchairs with a glass of raspberry squash and listen, waiting for my mother to finish work. She keeps telling everyone about my exceptional school results and the supplicants smile at me ingratiatingly. I am embarrassed, proud and pleased at the same time. I tell everyone I want to be a poetess when I grow up.

It is 8 March, International Women's Day. Most of the visitors and quite a few employees bring in a bunch of flowers or a box of chocolates. My mother's desk is covered with cards, some of them with the picture of Klara Zetkin, the German communist leader, whose square jaw reminds me of Stanka. By the end of the afternoon, the hyacinths almost overpower the smell of smoke. I am here to help Mother carry the presents into the car: it is one of my annual treats. For days and even weeks after 8 March we visit relations and friends, distributing the boxes of chocolates and potted hyacinths Mother got.

My father waits in our white Skoda outside. During the drive home, as always at the end of the working day, my mother runs through events from the office in detail, but Father switches off after a minute or two. You can tell when he is not listening any more from the automatic intervals between his yeses, but she carries on regardless. It is the telling rather than his responses that seems to matter to her. My sister and I know all of the many dramatis personae of Mother's office life by name, ethnic origin and family situation. We know their illnesses, their children's misadventures at school, the location of their summer houses and allotments, details of their spouses' jobs. My father never talks about his work. If you ask him what he does at the office, he normally says that he sharpens pencils or some such lark.

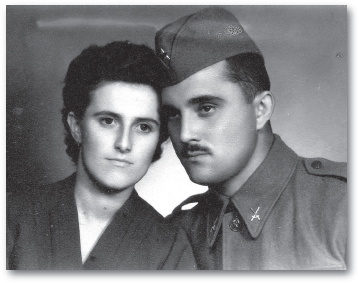

My parents, before me

Mother leaves home at five-ten every morning in order to be at work at six-thirty. The ticket kiosks throughout Belgrade open at seven o'clock and she has a whole series of telephone calls to make beforehand. At seven, she telephones home to wake up my sister and me for school. She tells us what she's put out for breakfast on the kitchen table and which clothes she's hung on the towel rail, and sometimes asks, âWhat's new?' absent-mindedly, as though anything much could have happened in the two hours of sleep we've had since she left. At other times she says, â

Molim

' â âYes please' â as though we'd rung her. When we play office, my sister and I emulate this particular tone on imaginary air telephones. In fact, we often play office, and my mother brings empty form books, paper clips and pieces of used indigo paper so that we can issue forms in triplicate. We even have our special office names for the game. My sister â who is normally

my secretary â calls herself Clementine. I chide her about sloppy form-filling, and she bangs her imaginary carriage return in noisy protest.

Most people in our street go to work an hour later than my mother. Often, when I leave for school, I see her small footprints like rows of hurried exclamation marks in untouched snow. I know that she was the first person in the entire street to leave her warm house in the morning, to take her seat on an empty bus whose wheels churn the icy slush in semi-darkness. At eleven, I am already taller than her, with longer, wider feet. I feel strangely protective towards Mother's traces: their edges soften and blur as the day progresses.

My favourite time of day is the early afternoon, when we are back from school and my parents are not yet home. My sister and I riffle through the mail, telephone friends, cut pictures out of magazines and play music very, very loudly. We are latchkey children of sorts. My paternal grandmother lives on the floor below (our New House is three storeys high), but she is at work on her land most days between late February and late October. She tends to return at dusk with bags of fresh vegetables. We still own half a dozen acres of land in the Makish valley, most of it under maize, and my grandmother keeps an acre or so for tomatoes, peas, beans, lettuce and radishes. My sister and I love the smallest of new potatoes, which are barely bigger than pearls. Granny's vegetable patch is reached through a narrow path in fields of corn, with long dark sabres of leaves which make the wind sound like a distant waterfall.

My mother comes back from work at four o'clock, with bags of ingredients for supper, breakfast and the next day's lunch. She prepares the evening meal and the next day's lunch at the same time every evening. Between five and seven, the

kitchen is a noisy, steamy cauldron of activity; this is the best time to hide away in one's room pretending to be doing urgent homework, while in fact writing poetry or simply staring out of the window, daydreaming.

My father also returns around four with a briefcase and a newspaper, and often with warm loaves of bread under his arm. He and my mother sometimes catch up with each other on the short walk from the bus stop. She travels home by public transport and he in special army buses which pick him up from the same street corner every morning and drop him off every afternoon, like khaki school buses for grey-haired boys. The schoolboy impression is reinforced by the fact that Father often carries his gym bag in his briefcase. He regularly puts in an hour's swimming or a game of five-a-side football at the end of his working day.

Between four and five he usually has his siesta. He summons my sister or myself to tell him about our day at school. Our stories, he claims, lull him more easily to sleep. At five, he wakes up and promptly disappears downstairs, to the manly equivalent of the kitchen cauldron â things which involve neat kits of screwdrivers, pots of paint and polish, the car with its bonnet open, like the shoe-house of the fairy tale.

Early on, I begin to think that I should have been born a boy. I can't break an egg without making a mess of it, while I am usually exceedingly quick at grasping the interior mechanisms of every domestic appliance and the precise order of the bulbs behind the TV screen. A sole man in a household of four women, my father welcomes my interest, though the guilt associated with joining him rather than my mother in the kitchen most frequently keeps me in my room, writing.