Challenging Depression & Despair: A Medication-Free, Self-Help Programme That Will Change Your Life (11 page)

Authors: Angela Patmore

Tags: #Self-Help, #General

My reputation as a Heartless Bitch will perhaps have forewarned you that this is one book on depression where you won’t get an easy ride

. Unlike many of my fellow advisers on mental health issues, I’m not trying to calm you down or mollycoddle your feelings. I regard it as my responsibility to get you to face the Demon of Despair, deal with it robustly and truly get better. I happen to think you are more likely to do this if you face reality than if you face somewhere else, pop pills and imagine calm scenes.

So this chapter has to start by giving you a fright.

Health warning

Hopeless and helpless people should understand that, even if they have never attempted suicide, they may be allowing themselves to get sick and even to die by their failure to help themselves.

Research on despair shows that it makes the sufferer vulnerable to harmful physiological changes. In America in the 1970s, depressed patients were interviewed about their feelings while they were wired up to monitoring equipment, and the scientists found that even

talking

about feelings of hopelessness and helplessness may cause a sudden drop in blood pressure sufficient to be life-threatening, even though the speaker may be completely unaware of any physiological change.

1

Earlier, in the late 1960s, Martin Seligman and Steven Maier carried out experiments that were to change the face of modern psychology. Seligman and Maier discovered that:

1

If they exposed laboratory animals or human volunteers to painful situations, their normal response was to try to escape and avoid the pain. This was not unexpected.

2

If they could not escape, most of them gradually resigned themselves and exhibited apathetic behaviour. This was not unexpected either.

3

What was unexpected was that even if an escape hatch was then provided, some of these pathetic subjects continued to behave in a resigned way, putting up with the pain and not trying to save themselves.

Afterwards their resignation was found to have quite dramatically undermined their health. It became clear that giving up is maladaptive and harmful to survival because it disrupts the body’s defences and exposes it to pathogens. The scientists called the behaviour they had seen ‘learned helplessness’ or ‘failure to initiate responses in the face of threat’.

2

Martin Seligman went on to develop a model of depression based on his experimental work.

RESIGNATION, NOT ‘STRESS’

Resignation is quite different from arousal. In fact the reaction is the biological

opposite

of the fight-or-flight response designed to galvanise our brains and bodies to meet challenges (that many are now calling ‘stress’). Learned helplessness, in contrast, is a kind of biological death wish. It is very useful, for example, to a gazelle about to face imminent slaughter by a predator. Resignation numbs the threatened creature by releasing opiate-like substances in the brain to calm it for its impending ugly fate. It acts as an anaesthetic and as a painkiller. The fact that the response shuts off the immune system (called ‘auto-immune suppression’) is perhaps no surprise: if you are just about to die, you hardly need an immune system.

THE STING IN THE TAIL

The sting in the tail is this: if an animal – or indeed a person – is not facing imminent violent destruction, the helpless response shuts off the immune system

anyway

. It kills while it calms. Meanwhile all attempts at self-help appear futile, because opiate-like natural substances known as pentapeptides are being released into the nervous system to anaesthetise the inert individual from present pain and

future action. This is why, in humans, helplessness is likely to increase feelings of pointlessness, desolation and despair.

There is robust research evidence on the health consequences of resignation from studies of prisoners of war, survivors of concentration camps (describing those who had succumbed) and bereaved spouses. Insurance companies are familiar with the potentially lethal effects on middle-aged men who ‘give up the ghost’ having lost their jobs. Their survival can no longer be guaranteed.

Helplessness – a case study

In my work as a Restart trainer, I often came across jobseekers who had ‘given up’, not only on looking for work but on everything else as well. So I would read them a press clipping to illustrate the potentially lethal consequences of resignation. The article was about 27-year-old Andrew Thomas of Glamorgan, who died after being made redundant. Pathologist Dr David Stock said Mr Thomas appeared to have been ‘a completely healthy young man’ and the cause of his death was ‘unascertainable’. After initial attempts to find work, Mr Thomas had begun getting up late and spending every day watching videos and television. He even gave up getting dressed and would sit all day in his pyjamas. His father Gwilym was reported to have said after the hearing, ‘I believe he lost the will to live.’

3

The learned helplessness research may clarify the mystery of what ‘stress’ scientists mistakenly and inaccurately refer to as ‘long-term stress’, which they blame for harming our health. The confusion has led to a great deal of misinformation being given to the public about ‘stress’ arousal and disease links. People are being constantly warned about the fight-or-flight response – a survival mechanism that can save them – and not warned about the opposite response – resignation – that can kill them.

THE HELPLESS PROFILE

How does somebody suffering from despair identify this helpless mindset? Here are some of the attributes typical of the helpless personality:

•

low self-esteem

•

poor coping skills

•

‘can’t be bothered’ attitude

•

avoidance of ‘scenes’ or conflict

•

unwillingness to face problems head on

•

submission (often with resentment)

•

escapist calming habits, e.g. alcohol, nicotine, etc.

•

escapist games-playing, television, DVD-watching, etc.

•

not fighting back

•

resigned and apathetic attitude

•

fatalism (‘what will be will be’).

Helpless individuals will resort to strategies that avoid confronting problems or threats, preferring to cling to calming ‘painkilling’ habits like tobacco, cannabis, alcohol and comfort-eating, even though they know these to be potentially harmful to their health. The resigned person simply doesn’t care. He or she hears all the time comments from others that they are ‘hopeless’ – and indeed they are. Their fate generally hangs in the balance, or by a seriously disabled spider’s last cobweb. A common phrase used in my classes was

I

can’t be arsed

. The helpless have given up trying to save themselves and turned their back on a threatening situation. This approach to life is not only abject but extremely dangerous.

HELPLESS THINKING

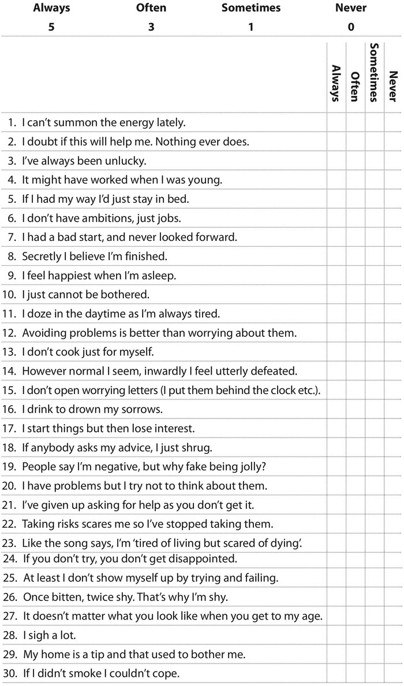

Do the following thoughts occur to you? Tick the relevant boxes and score yourself on each statement.

Scores

| 0–45 | Even though you may be depressed right now you are really self-determining. You are a survivor and make your own luck. |

| 45–80 | You don’t give up easily. When disaster strikes you will generally find out how to cope. |

| 80–115 | You are prone to letting others decide your fate. Stand your ground and make the effort. You decide. |

| 115–150 | You have the most to gain by changing, as your whole life is waiting out there for you. Stop drifting over the waterfall. Wake up and take control right now . |

HOW

NOT

TO BE HELPLESS

So what can you do if your habits are helpless as well as hopeless? Use this panel: photocopy it or cut it out and paste it on the wall. Send it to yourself as an e-mail. Stick it on your mirror. Nail it to the back gate. It is very important.

The first step is REALISATION.

Understand and recognise what your behaviour is doing to you, and to your body, and that you are committing slow-motion suicide.

The second step is to TAKE CONTROL.

So long as you act helpless and ‘give up’, you relinquish control of your life to others, and to chance. Take back control. Be the master of your fate. This is your life. Live it.

The third step is to STOP TRYING TO ESCAPE.

Don’t try to outrun reality – you’ll never make it! In the long run, and even the short run, escapist behaviour won’t make you safer. It won’t even make you feel more secure, because it lowers your self-esteem and leaves you vulnerable. You render yourself defenceless in a scary place. And meanwhile, the problem itself gets bigger with time because you have failed to address it.

The last step is to learn the simple truth: BEST TO FACE THE WORST.

Turn and embrace challenges. Face problems head on. Our whole culture is full of examples of facing down monsters and robbing them of their power because as a race we have learned this generally works. When we run from monsters, they grow. When we turn and face them, they diminish. Whatever the problem or threat you are trying to avoid, it is unlikely to be as dangerous to your mind and body as the harm you are doing to yourself. The moment you make the decision to get off your behind and help yourself, you will feel a surge of energy. Try it – you’ll like it. You will feel different because your brain will support you. Remember: it is designed to help you survive.

THE NEED FOR PRESSURE

If resignation is nature’s way of anaesthetising us, what does this tell us about the opposite, more proactive style of living such as:

•

facing reality

•

accepting challenges

•

meeting threats