Carrier (1999) (24 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

Forward of the living spaces, in the very bow of the ship, is the forecastle. Here the anchors, handling gear, and their huge chains are located. It is also the domain of the most traditional jobs in the Navy: the Deck Division. In an era of computers and guided weapons, these are the sailors who can still tie every kind of knot, rig mooring lines, and handle small boats in foul weather. You need these people to operate anything bigger than a rowboat, and aboard a carrier they are indispensable. On the port side of the forecastle you find the first of a set of “stairs,” which we’ll use to climb up several levels. These are not conventional stairways, but very nearly vertical ladders, and they are quite narrow. You learn to move up and down ships’ ladders carefully, and finding a handy stanchion to grasp when you’re on them becomes instinctive.

Opening another hatch, you find yourself on a small platform adjacent to the bow. From here, you can climb a few steps and move out onto the four and a half acres that is the carrier’s flight deck. Again, the spongy feel of the deck tells you that there is non-skid under your feet. Around the deck, two or three dozen aircraft are packed in tight clusters, to free as much deck space as possible. During flight operations, the noise is incredible. It is so loud that you must wear earplugs just to watch from up on the island, while flight deck personnel who must work among the aircraft wear special “cranial” helmets with thickly padded ear protectors to preserve their hearing. Only Landing Signals Officers (LSOs, the people who guide aircraft during landings) are allowed on deck during flight operations without a cranial, since they have to clearly hear and see aircraft as they approach the stern for landing.

There are other hazards as well. In fact, the flight deck of a modern aircraft carrier is arguably the most dangerous workplace in the world. Aircraft are constantly threatening to either suck flight deck personnel into their engines, or blow them off of the deck into the ocean. For this reason, the entire perimeter of the flight deck and the elevators is rigged with safety nets. In addition, everyone on the flight deck also wears a “float coat,” which is an inflatable life jacket with water-activated flashing strobe light, and a whistle to call for help—just in case the safety nets don’t catch you. Standard flight deck apparel also includes steel-toed boots, thick insulated fabric gloves, and goggles (in case a fragment of non-skid or some foreign object/ debris—FOD—is blown into your face).

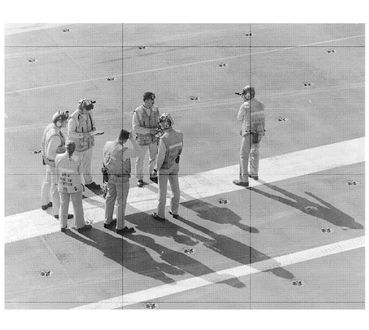

Flight deck personnel aboard the USS

George Washington

(CVN-73).

George Washington

(CVN-73).

JOHN D. GRESHAM

Each float coat and cranial is color-coded by job. Under the float coats, deck crews also wear jerseys—heavy, long sleeved T-shirts—of the same color as the float coat (though they may be a different color from the cranials). These color-code combinations are universal aboard Navy ships. Here is what they mean:

DECK PERSONNEL IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

For example, only sailors wearing purple coats, jerseys, and cranials are allowed to handle fuel and other flammable fluids on deck (they are nicknamed the “grapes”).

Keeping an eye on flight-deck operations is a vital task. Up on the island, observers constantly watch the position and flow of planes, personnel, and equipment around the deck. Any deviation from standard procedures or safety rules calls down a sharp and angry rebuke over the flight deck loudspeaker (loud enough to hear through your cranial—and that is really LOUD) telling you

exactly

what you must do

RIGHT NOW!

To help these commands make sense, there is a standard set of coordinates and definitions for the various parts of the flight deck. For example, the catapults are numbered from 1 through 4 in order, starboard to port, bow to stern. The elevators are numbered, with 1 and 2 ahead of the island on the starboard side, number 3 just aft, and number four on the port side aft. The jet blast deflectors (JBDs) are matched to the catapults, 1 through 4. The arresting wires are also numbered, running from number 1 farthest aft, to number 4 up forward. Areas of the deck also have specific names, so that when an observer or lookout yells out a warning, he can direct other eyes to it without delay. Some examples include:

exactly

what you must do

RIGHT NOW!

To help these commands make sense, there is a standard set of coordinates and definitions for the various parts of the flight deck. For example, the catapults are numbered from 1 through 4 in order, starboard to port, bow to stern. The elevators are numbered, with 1 and 2 ahead of the island on the starboard side, number 3 just aft, and number four on the port side aft. The jet blast deflectors (JBDs) are matched to the catapults, 1 through 4. The arresting wires are also numbered, running from number 1 farthest aft, to number 4 up forward. Areas of the deck also have specific names, so that when an observer or lookout yells out a warning, he can direct other eyes to it without delay. Some examples include:

•

The “Crotch”

—The point where the roughly 14° landing deck “Angle” ends and the port bow begins.

The “Crotch”

—The point where the roughly 14° landing deck “Angle” ends and the port bow begins.

• The “Junkyard”—The area at the base of the island aft. Here tractors, forklifts, a wrecking crane, and the world’s smallest fire truck (collectively known as “yellow gear” even though some are now painted white) are parked, always ready to move when needed.

•

The “Hummer Hole”

—The area just forward of the Junkyard. Here the E-2C Hawkeyes (nicknamed “Hummers”) and their cargo-carrying cousins, the C-2 Greyhounds, are parked.

The “Hummer Hole”

—The area just forward of the Junkyard. Here the E-2C Hawkeyes (nicknamed “Hummers”) and their cargo-carrying cousins, the C-2 Greyhounds, are parked.

•

The

“Street”—The “ Street” is up on the bow in the area between Catapults 1 and 2; the forward catapult control pod is located there.

The

“Street”—The “ Street” is up on the bow in the area between Catapults 1 and 2; the forward catapult control pod is located there.

•

The “Rows”

—Also on the bow are the “1 Row” and “2 Row.” These are the zones outboard of Catapults 1 and 2 and are normally used as parking areas for the F/A-18 Hornets when a landing event is active.

The “Rows”

—Also on the bow are the “1 Row” and “2 Row.” These are the zones outboard of Catapults 1 and 2 and are normally used as parking areas for the F/A-18 Hornets when a landing event is active.

•

The “Finger”

—A narrow strip of deck just aft of Elevator 4, with parking space for a single plane.

The “Finger”

—A narrow strip of deck just aft of Elevator 4, with parking space for a single plane.

Working in this noisy, hot, and dangerous world is the job of some of the bravest young men and women you will ever meet. Most are under twenty-five; and some look so naive (or so scary), you might not trust them to valet park your car at a restaurant. Yet the Navy trusts them to safely handle aircraft worth several

billion

dollars, not to mention the infinitely precious lives of air crews, each representing millions of dollars in training and experience.

billion

dollars, not to mention the infinitely precious lives of air crews, each representing millions of dollars in training and experience.

Theirs is a world of extremes. For up to eighteen hours a day, they’re subjected to noise that would deafen if not muffled; heat and cold that would kill if not insulated. They are surrounded by explosives, fuel, and other dangerous substances,

36

and are frequently buffeted by winds of over sixty knots. For this, they receive a special kind of respect and a “hazardous duty” bonus (in 1998, about $130 per month) in addition to their sea pay. These young men and women know their work makes flying aircraft on and off the boat possible, and they take quiet pride in this dirty, dangerous job up on “the roof.” Because of the extreme noise, a richly expressive sign language is used to direct operations on the flight deck. Using a series of common and easily understood hand signals, the deck crew personnel tell each other how to move aircraft and load bombs and equipment, and warn each other of emergencies. They constantly watch out for each other, for only the brother or sister sailor looking out for you keeps you safe. All of these efforts are dedicated to just two basic tasks: the launching and landing of aircraft. Let’s now look at how it is done in somewhat greater detail.

36

and are frequently buffeted by winds of over sixty knots. For this, they receive a special kind of respect and a “hazardous duty” bonus (in 1998, about $130 per month) in addition to their sea pay. These young men and women know their work makes flying aircraft on and off the boat possible, and they take quiet pride in this dirty, dangerous job up on “the roof.” Because of the extreme noise, a richly expressive sign language is used to direct operations on the flight deck. Using a series of common and easily understood hand signals, the deck crew personnel tell each other how to move aircraft and load bombs and equipment, and warn each other of emergencies. They constantly watch out for each other, for only the brother or sister sailor looking out for you keeps you safe. All of these efforts are dedicated to just two basic tasks: the launching and landing of aircraft. Let’s now look at how it is done in somewhat greater detail.

A top view of an improved

Nimitz

-class (CVN-68) nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

Nimitz

-class (CVN-68) nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

JACK RYAN ENTERPRISES, LTD., BY LAURA DENINNO

If you move aft from the bow down the “Street,” you walk between the two bow catapults, each as long as an American football field. And there is a similar catapult arrangement on the landing “angle” on the port side. Most of the machinery for each C13 Mod. 1 catapult is concealed under the flight deck: two slotted cylinders in a long steel trough, each with a narrow gap along the top. Overlapping synthetic rubber flangles cover and seal the gaps. In each cylinder is a piston, with a lug projecting through the sealing strips on top. Each of these lugs leads to a small crablike fixture called a “shuttle,” which is up on the flight deck.

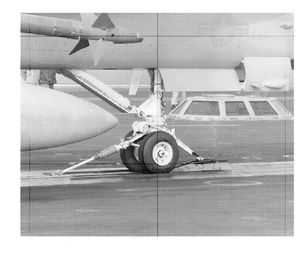

When an aircraft is ready to launch, it is maneuvered into position under the guidance of a plane handler. When the nosewheel is just behind the shuttle, a metal attachment on the gear strut, called a towbar, is lowered into a slot on the shuttle. Meanwhile, the Jet Blast Deflector (JBD) just aft of the plane is raised, and another mechanical arm is attached to the rear of the nose gear strut with a device called a “holdback.”

37

This allows the aircraft to run its engines up to full power, far beyond the ability of the plane’s brakes to keep it on the deck. In this way, the bird will have a considerable forward thrust even before it starts moving. Each aircraft type in the wing has its own special color-coded holdback, to prevent them from being used mistakenly on the wrong bird. The exceptions are the F-14 Tomcat and F/ A-18 Hornet, which have permanent holdback devices built into their nosewheelgear struts.

37

This allows the aircraft to run its engines up to full power, far beyond the ability of the plane’s brakes to keep it on the deck. In this way, the bird will have a considerable forward thrust even before it starts moving. Each aircraft type in the wing has its own special color-coded holdback, to prevent them from being used mistakenly on the wrong bird. The exceptions are the F-14 Tomcat and F/ A-18 Hornet, which have permanent holdback devices built into their nosewheelgear struts.

The nose gear of an F/A-18C Hornet on the #1 Catapult of the USS

George Washington

(CVN-73). The forward towbar is linked to the catapult shuttle, and the holdback device is in position.

George Washington

(CVN-73). The forward towbar is linked to the catapult shuttle, and the holdback device is in position.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

Once the aircraft is properly hooked up by one of the green-shirted catapult crewmen, another “green shirt” holds up a chalkboard with the plane’s expected takeoff weight written on it for the pilot and catapult officer (down in the catapult control pod) to see. If both agree that the number is correct (confirmed by hand signals), then the catapult officer (known as the “shooter”) begins to fill the twin pistons with a pressurized charge of saturated steam from the ship’s reactor plant.

38

The steam pressure is carefully regulated to match the takeoff weight of the aircraft, the speed of the wind over the deck (this is the natural wind speed plus the speed of the ship), and other factors like heat, air pressure/density, and humidity. This has to be very precise. Too much pressure will rip the nosewheel gear out of the plane, while too little will cause a “cold shot.” In a cold shot, the aircraft runs down the deck and never reaches takeoff speed; the catapult then hurls it into the water ahead of the onrushing carrier.

39

At best, the crew will eject and the aircraft will be lost. At worst, both the aircraft and flight crew will be lost. As might be imagined, catapult officers (who are themselves veteran carrier aviators) take this highly responsible job quite seriously.

38

The steam pressure is carefully regulated to match the takeoff weight of the aircraft, the speed of the wind over the deck (this is the natural wind speed plus the speed of the ship), and other factors like heat, air pressure/density, and humidity. This has to be very precise. Too much pressure will rip the nosewheel gear out of the plane, while too little will cause a “cold shot.” In a cold shot, the aircraft runs down the deck and never reaches takeoff speed; the catapult then hurls it into the water ahead of the onrushing carrier.

39

At best, the crew will eject and the aircraft will be lost. At worst, both the aircraft and flight crew will be lost. As might be imagined, catapult officers (who are themselves veteran carrier aviators) take this highly responsible job quite seriously.

Other books

Open Heart by Elie Wiesel

Master of Pleasure by Adriana Hunter

Lady Falls (Black Rose Trilogy) by Bernard, Renee

She Can Shift (Interracial Shifter Romance BWWM) by Archer, Tia

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank: Stories by Nathan Englander

Lost Boi by Sassafras Lowrey

Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez

Dead Spy Running by Jon Stock

Emperor Mage by Pierce, Tamora