Carrier (1999) (22 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

Before this can begin, any other ships in Dry Dock 12 are floated out and the movable cofferdam is removed. Then the dock is carefully flooded, with hundreds of NNS and Navy personnel monitoring tidal conditions and the watertight integrity of the carrier. When the dock is fully flooded and the ship has lifted off the keel blocks, the gate is opened. Now things happen fast. As a small tugboat pulls the carrier out of the dry dock, other tugboats wait just outside in the river to take control of the massive hulk. When the carrier is finally clear of the gate and safely into the deep channel of the river, it is turned and towed downstream to the fitting-out wharf on the southern end of the NNS property. Here it will be moored until it is turned over to the Navy, approximately two years later.

While it is an impressive sight sitting at the fitting-out dock, the mass of metal floating there is hardly a ship of war. It is still, in naval terminology, just a “hulk.” Making it into a habitable vessel is the job of almost 2,600 NNS yard workers—everything from nuclear-reactor engineers to diesel-engine mechanics, computer specialists to roughneck welders. Building a modern warship takes almost every technology and tradecraft known. Imagine a skyscraper with offices, restaurants, workshops, stores, and apartments that can steam at more than thirty knots, with a four-and-a-half-acre airfield on the roof. That is a fair description of a

Nimitz-

class aircraft carrier.

Nimitz-

class aircraft carrier.

During a visit to NNS in the fall of 1997, I spent some time aboard the USS

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) while she was about nine months from commissioning and delivery. I’d like to share with you some of my experiences there. My first stop, after NNS and Navy officials led me aboard, was the massive hangar deck. At 684 feet/208.5 meters long, 108 feet/33 meters wide, and 25 feet/7.6 meters tall, it is designed to provide a dry, safe place to store and maintain the aircraft of the embarked wing. As we walked forward, I passed several large access holes that led into the two nuclear reactor compartments below. These would be buttoned up shortly, my guides told me. The nuclear fuel packages would then be installed, followed by testing and certification of the twin A4W reactor plants. All around the hangar deck, workers were busy welding and installing pieces of equipment.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) while she was about nine months from commissioning and delivery. I’d like to share with you some of my experiences there. My first stop, after NNS and Navy officials led me aboard, was the massive hangar deck. At 684 feet/208.5 meters long, 108 feet/33 meters wide, and 25 feet/7.6 meters tall, it is designed to provide a dry, safe place to store and maintain the aircraft of the embarked wing. As we walked forward, I passed several large access holes that led into the two nuclear reactor compartments below. These would be buttoned up shortly, my guides told me. The nuclear fuel packages would then be installed, followed by testing and certification of the twin A4W reactor plants. All around the hangar deck, workers were busy welding and installing pieces of equipment.

Catapult-testing deadweights aboard the

Harry Truman

(CVN-75).

Harry Truman

(CVN-75).

JOHN D. GRESHAM

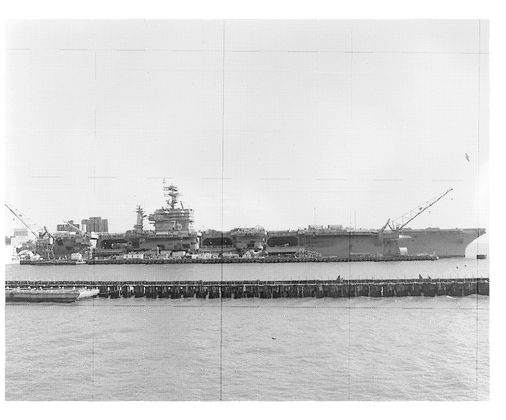

The hulk of the USS

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) at the NNS fitting-out wharf in the fall of 1997. By mid-1998, the

Truman

was conducting sea trials off the Atlantic Coast.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) at the NNS fitting-out wharf in the fall of 1997. By mid-1998, the

Truman

was conducting sea trials off the Atlantic Coast.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

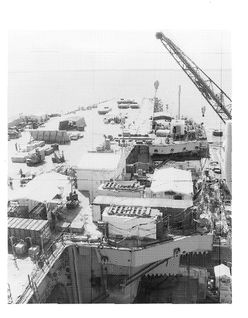

After climbing several ladders, we emerged on the flight deck, where hundreds more NNS workers were hustling about at their tasks, and then moved forward to the catapults, which were in the process of testing and certification. They are installed in pairs on the bow and the deck angle port-side, and each of the four 302-foot/92.1-meter-long C13 Mod. 1 catapults is capable of launching an aircraft every few minutes (the cycle time depends largely on the skill of the deck crew). Each catapult is powered by a pair of steam cylinders, which are built into the flight deck, and normally use high-pressure saturated steam from the reactor plant; but since the reactors were not yet powered up,

Truman

drew her power, water, and steam from plants dockside.

Truman

drew her power, water, and steam from plants dockside.

Testing such powerful machines is a dramatic procedure. Scattered around the deck were a number of orange-painted, water-filled, wheeled trolleys called deadweights. Each deadweight simulates a fully loaded aircraft, with attachment points that allow it to be hitched to the shuttle of a catapult. After the bow has been pointed into the James River channel, and the Coast Guard and local boaters have been suitably warned, each catapult fires the entire range of deadweights. The tests are noisy and the sight of the weights flying hundreds of yards/meters into the channel is bizarre. Nevertheless, this is a highly effective way to prove that the machinery is ready. After leaving the catapults, we headed aft to inspect the catapult control station between Catapults 1 and 2.

35

Set on a hydraulically raised platform under an armored steel door, the control station is a pod where the catapult officer—or “shooter”—can control the catapults in safety and comfort. Another identical station is located on the port side, controlling Catapults 3 and 4.

35

Set on a hydraulically raised platform under an armored steel door, the control station is a pod where the catapult officer—or “shooter”—can control the catapults in safety and comfort. Another identical station is located on the port side, controlling Catapults 3 and 4.

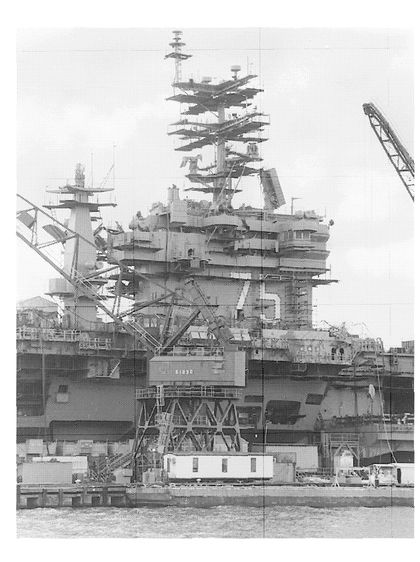

The island structure of the

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) being finished at NNS.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) being finished at NNS.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

Next we walked over to the island structure, where our guides showed us how the many systems on the flag and navigation bridges, the primary flight control, and the meteorology office were installed. Although the basic

Nimitz

design is over thirty years old, the many changes bringing it into the 21st century are quite visible. Up on the

Truman’s

navigation bridge, for example, are many of the “Smart Ship” systems (mentioned in the second chapter) that make it possible for three people to steer the ship from auto-matedcontrol stations (before, almost two dozen people were required to do the same job). Similar systems will be scattered throughout the

Truman,

and will be tested when she goes to sea in 1998.

Nimitz

design is over thirty years old, the many changes bringing it into the 21st century are quite visible. Up on the

Truman’s

navigation bridge, for example, are many of the “Smart Ship” systems (mentioned in the second chapter) that make it possible for three people to steer the ship from auto-matedcontrol stations (before, almost two dozen people were required to do the same job). Similar systems will be scattered throughout the

Truman,

and will be tested when she goes to sea in 1998.

The cluttered flight deck of the

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) while being fitted out at NNS.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) while being fitted out at NNS.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

As we moved farther aft, we passed by the kinds of tool sheds and other temporary storage buildings that you find at any construction site. Then we dropped down a ladder back to the hangar deck and down another into the bowels of the ship. At this point, the primary work on

Truman

involved preparing some eight hundred (out of a total 2,700) compartments for turnover to the Navy. Those compartments contain crew berthing, medical facilities, galley and mess areas, office spaces, the ship’s store, the post office, and storage rooms. Everything needed to finish these spaces must be carried up and down ladders and through narrow passageways by hand. Sprained knees and ankles are the price paid to haul paint cans, power cables, and tools into the ship.

Truman

involved preparing some eight hundred (out of a total 2,700) compartments for turnover to the Navy. Those compartments contain crew berthing, medical facilities, galley and mess areas, office spaces, the ship’s store, the post office, and storage rooms. Everything needed to finish these spaces must be carried up and down ladders and through narrow passageways by hand. Sprained knees and ankles are the price paid to haul paint cans, power cables, and tools into the ship.

Shortly after this job was completed, just after New Year’s of 1998, the first of the Navy’s crew of “plankowners” arrived. Several of the ship’s spaces that had already been turned over proved to be spotless when we visited them; and the quality and workmanship are very impressive. In particular, the communications spaces, which were just being brought to life by a Navy crew, had the look and smell of a new automobile. As the final stop on my visit, I was allowed to visit the magazines and the pump room in the very bottom of the ship.

It was close to quitting time when we made our way back to the hangar deck, aft to the fantail, and down the access ramps to the dock. As we sat waiting for our tired leg muscles to loosen, the shift alarm went off, and we watched 2,600 NNS workers come off shift and head for home—an impressive sight. As they passed by us on the dock, I was reminded of the builders of the Egyptian pharaoh’s pyramids. Both groups labored to build a wonder of the world. Unlike the pharaoh’s slaves who hauled and stacked the stones in the desert, these people

have chosen

to labor at their “wonder of the world.” They

want

these jobs, take pride in what they do, and make good livings. For those who think that Americans don’t build anything worthwhile these days, I say go down to NNS and watch these great men and women build metal mountains that float, move, and fly airplanes off the top. It truly is the “NNS” miracle.

have chosen

to labor at their “wonder of the world.” They

want

these jobs, take pride in what they do, and make good livings. For those who think that Americans don’t build anything worthwhile these days, I say go down to NNS and watch these great men and women build metal mountains that float, move, and fly airplanes off the top. It truly is the “NNS” miracle.

The “NNS Miracle”: Some of the 2,600 Newport News Shipbuilding workers leave the

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) at the end of an afternoon shift.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) at the end of an afternoon shift.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

When the initial crew cadre came aboard Truman in early 1998, they began to help the NNS yard workers bring the ship’s various systems to life. This process (ongoing until the ship is handed over to the Navy) is designed to make her ready for her “final exams,” when the carrier will become truly seaworthy, with her reactors powered up and most of her “plankowner” crew aboard. Combat systems tests occur when the ship is about 98% complete, with evaluations of the radar and radio electronics, defensive weapons, and all the vast network of internal communications and alarms. After these tests, it is time for sea trials off the Virginia capes, including speed runs to evaluate the power plant. After these trials are completed, the Navy conducts one last series of inspections prior to the most important ceremony of the entire building process (at least for NNS). This is the signing of the Federal Form DD-250, which indicates that the Navy has taken possession of the vessel and NNS can now be paid!

The next six to eight months are filled with training and readiness exercises, including the traditional “shakedown” cruise. Following this is a short period of yard maintenance (known as “Post Shakedown Availability”) to fix any problems that have cropped up. The new carrier will then spend much of her time over at the Norfolk Naval Station, moored to one of the long carrier docks, where she will get ready for commissioning. At the commissioning ceremony, the high officials, the dignitaries, and the ship’s sponsor once again gather. Again there are speeches and presentations. And almost a decade after the decision was made to build this mighty warship, a signal is given, the commissioning pennant is raised, the crew rushes aboard to man the sides, and she is finally a warship in the U.S. Navy.

Other books

Fragmented by Eliza Lentzski

Only You by Denise Grover Swank

0765332108 (F) by Susan Krinard

Chance: An Action & Adventure Romance Novel (Sacrifice) by A.C. Heller

Truly Tasteless Jokes Three by Blanche Knott

The Blasted Lands by James A. Moore

The Right Moves - The Game Book 3 by Hart, Emma

The Soulblade's Tale by Jonathan Moeller

The Peppercorn Project by Nicki Edwards

Wide is the Water by Jane Aiken Hodge