Carrier (1999) (17 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

The decision about where an individual goes is based on several factors, most importantly where he or she finishes in the first part of their PFT class. Normally, high-scoring students are funneled into the “glamor” Naval aviation assignments, like the fighter/attack communities. Since air wing and carrier skippers have traditionally come from the “fast movers,” assignment to one of these communities carries great weight, status, and self-esteem. Still, more than a few young aviators choose other specialties, such as helicopters or support aircraft. Though one reason is that the skills of flying transport and cargo aircraft have greater value in the civilian job market, sometimes trainees just want to fly a particular kind of aircraft, or a specific mission. Whatever community the trainees want, the personnel detailers do their best to match these desires with the needs of the Navy and Marine Corps.

While every SNA undergoes a rigorous training regime, those in the Strike and E-2/C-2 pipelines clearly have the toughest challenge—learning to make arrested landings aboard aircraft carriers. You cannot overemphasize how

this

one skill, more than any other, sets Naval aviators apart from their land-based counterparts. Landing on a moving ship at sea is insanely difficult, and it must be done with absolute precision

every

time. In fact, no other phase of SNA training “washes out” so many young fliers. The defining moment for every naval aviator occurs when they come out of the break and line up into the “groove” for their first carrier qualification. Terrifying. Heart-stopping. Insane. That’s what they all think when they first look down and out at a carrier and realize they’ll have to land on

that

in just about fifteen seconds!

this

one skill, more than any other, sets Naval aviators apart from their land-based counterparts. Landing on a moving ship at sea is insanely difficult, and it must be done with absolute precision

every

time. In fact, no other phase of SNA training “washes out” so many young fliers. The defining moment for every naval aviator occurs when they come out of the break and line up into the “groove” for their first carrier qualification. Terrifying. Heart-stopping. Insane. That’s what they all think when they first look down and out at a carrier and realize they’ll have to land on

that

in just about fifteen seconds!

To survive your first set of carrier qualifications (naval aviators have to requalifiy literally dozens of times in the course of a career), the key is to make “good” landings as early as possible during qualifications. This is because your final score is an average of

all

your landing attempts. If you start out poorly, then you’ve dug yourself a hole that is almost impossible to get out of. The Navy likes SNAs who are “comfortable” and “natural” with the carrier landing process (as if this is

ever

possible!), and pilots who have to “learn” or “force” it are considered potentially dangerous, and not suited for the trade.

NFO Training: The Guys in Backall

your landing attempts. If you start out poorly, then you’ve dug yourself a hole that is almost impossible to get out of. The Navy likes SNAs who are “comfortable” and “natural” with the carrier landing process (as if this is

ever

possible!), and pilots who have to “learn” or “force” it are considered potentially dangerous, and not suited for the trade.

Pilots and NFOs need each other just to survive. And it’s not just part of the job. The men and women who fly for the sea services have a special bond; they look out for each other in the air and on the ground. This comradeship, added to the many other rewarding aspects of Navy flying, helps keep naval aviators coming back to reenlist. Just as with pilots, the path to becoming an NFO begins at NAS Pensacola, with the same six-week API course taken by SNAs. But then the SNFOs are assigned to their own PFT, run by VT-10. Here they spend fourteen weeks learning basic airmanship, including twenty-two hours of flying time in a PFT trainer. Though they spend eight of these in the pilot’s seat, they are not allowed to solo. The SNFOs then undergo an extensive PC-based training course in aircraft systems, which includes training on radio and navigation procedures, and classroom work in aerodynamics, emergency procedures, flight rules and regulations, and cockpit resource management. Once the basic PFT course is completed, the SNFOs continue onto their intermediate PFT courses via one of two pipelines: Navigator and Tactical Navigator Intermediate Training:

•

Navigator

—The Navigator pipeline supplies personnel for the P-3 and EP-3 Orion; C-130, KC-130, and HC-130 Hercules; and E-6 Mercury TACMO communities. Twenty-two weeks long, the Navigator course is run by the Air Force’s 562nd FTS at Randolph AFB, Texas. There, SNFOs in the Navigator pipeline complete eighty hours of airborne flight training in the T-43A trainer (a modified Boeing 737), learning the difficult trade of long-range and over-water navigation. These include use of celestial, radio, and satellite navigation equipment, as well as secure voice and data transmission systems.

Navigator

—The Navigator pipeline supplies personnel for the P-3 and EP-3 Orion; C-130, KC-130, and HC-130 Hercules; and E-6 Mercury TACMO communities. Twenty-two weeks long, the Navigator course is run by the Air Force’s 562nd FTS at Randolph AFB, Texas. There, SNFOs in the Navigator pipeline complete eighty hours of airborne flight training in the T-43A trainer (a modified Boeing 737), learning the difficult trade of long-range and over-water navigation. These include use of celestial, radio, and satellite navigation equipment, as well as secure voice and data transmission systems.

•

Tactical Navigator Intermediate Training—Every

SNFO who is not assigned to the Navigator course at Randolph AFB goes into the Tactical Navigator Intermediate Training (TNIT) pipeline. This course is designed to provide NFOs for all the “tactical” (i.e., combat) aircraft communities in the sea services—such as the F-14 Tomcat, the S-3B Viking, the E-2C Hawkeye, and the EA-6B Prowler. The TNIT SNFOs take their training with VT-10 at NAS Pensacola, and the course lasts fourteen weeks. The flight training for TNIT SNFOs primarily provides experience in low-level navigation and air-traffic-control procedures and is currently accomplished in contractor-operated T-39Ns (modified Sabreliner business jets); but this will change shortly, as the services begin transitioning over to jointly operated T-1A Jayhawks. Already, the T-1As are augmenting the T-39Ns for navigational training hops. Upon completion of TNIT, SNFOs are then assigned to one of three advanced training courses:

Tactical Navigator Intermediate Training—Every

SNFO who is not assigned to the Navigator course at Randolph AFB goes into the Tactical Navigator Intermediate Training (TNIT) pipeline. This course is designed to provide NFOs for all the “tactical” (i.e., combat) aircraft communities in the sea services—such as the F-14 Tomcat, the S-3B Viking, the E-2C Hawkeye, and the EA-6B Prowler. The TNIT SNFOs take their training with VT-10 at NAS Pensacola, and the course lasts fourteen weeks. The flight training for TNIT SNFOs primarily provides experience in low-level navigation and air-traffic-control procedures and is currently accomplished in contractor-operated T-39Ns (modified Sabreliner business jets); but this will change shortly, as the services begin transitioning over to jointly operated T-1A Jayhawks. Already, the T-1As are augmenting the T-39Ns for navigational training hops. Upon completion of TNIT, SNFOs are then assigned to one of three advanced training courses:

•

Strike SNFO:

The Strike SNFO course provides advanced training for NFOs heading into the S-3 Viking, ES-3 Shadow, and EA-6B communities. This course is run by VT-86 at NAS Pensacola. Flying in the T-2C (soon to be replaced by the T-45), T-39N, and T-1A. Strike pipeline SNFOs spend sixty flight hours over eighteen weeks learning over-water and low-level navigational procedures. The key course objective is to build crew coordination skills, so that in the heat of a combat or emergency situation, they will be ready to act to survive and complete their assigned missions. Once they complete the Strike course, the SNFOs destined for the EA-6B and ES-3 communities go to a special electronic warfare course at Corry Station on NAS Pensacola. S-3 SNFOs go straight into the S-3 community once they finish their training.

Strike SNFO:

The Strike SNFO course provides advanced training for NFOs heading into the S-3 Viking, ES-3 Shadow, and EA-6B communities. This course is run by VT-86 at NAS Pensacola. Flying in the T-2C (soon to be replaced by the T-45), T-39N, and T-1A. Strike pipeline SNFOs spend sixty flight hours over eighteen weeks learning over-water and low-level navigational procedures. The key course objective is to build crew coordination skills, so that in the heat of a combat or emergency situation, they will be ready to act to survive and complete their assigned missions. Once they complete the Strike course, the SNFOs destined for the EA-6B and ES-3 communities go to a special electronic warfare course at Corry Station on NAS Pensacola. S-3 SNFOs go straight into the S-3 community once they finish their training.

•

Strike/Fighter SNFO:

The Strike/Fighter SNFO pipeline provides NFOs for the small community of two-seat strike fighters in service in the Navy (F-14 Tomcats) and Marine Corps (F/A-18D Hornets). While similar to the Strike syllabus, the Strike/Fighter SNFO course is longer (twenty-five weeks) to allow the teaching of airborne intercept and radar skills, air combat maneuvering, and air-to-ground weapons deliveries.

Strike/Fighter SNFO:

The Strike/Fighter SNFO pipeline provides NFOs for the small community of two-seat strike fighters in service in the Navy (F-14 Tomcats) and Marine Corps (F/A-18D Hornets). While similar to the Strike syllabus, the Strike/Fighter SNFO course is longer (twenty-five weeks) to allow the teaching of airborne intercept and radar skills, air combat maneuvering, and air-to-ground weapons deliveries.

•

Aviation Tactical Data System (ATDS) SNFO:

The ATDS SNFO course provides airborne controllers for the E-2C Hawkeye community. This pipeline is unique in that it is run by an actual fleet unit, Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 120 (VAW-120) at NAS Norfolk, Virginia. The thirty-two hours of ATDS flight training (spread over twenty-two weeks) take place aboard actual fleet E-2C aircraft (also unique in SNFO training).

Aviation Tactical Data System (ATDS) SNFO:

The ATDS SNFO course provides airborne controllers for the E-2C Hawkeye community. This pipeline is unique in that it is run by an actual fleet unit, Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 120 (VAW-120) at NAS Norfolk, Virginia. The thirty-two hours of ATDS flight training (spread over twenty-two weeks) take place aboard actual fleet E-2C aircraft (also unique in SNFO training).

Now the new aviators can savor their achievements. They have reached the crowning moment when they are issued their naval aviator number and their “Wings of Gold.” Since the earliest days of naval aviation, this small pin has been the symbol that has set them apart from other officers in the sea services. It is now time for them to join the communities and aircraft that will be at the center of their naval careers for the next two decades.

But before they head out to their first fleet assignment, there is one more school for some of the new naval aviators. This is the notorious SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape) training course, one of the toughest courses any military officer can take. Though its exact details are classified, I do know that it is designed to take “at risk” pilots who will be entrusted with “special” knowledge or responsibilities, and place them into a “real-world” prisoner-of-war (POW) situation. SERE training faces the student with physical and mental stresses similar to those they might expect to experience if they are captured by one of our more unpleasant enemies (North Korea, Iran, Iraq, etc.). As of 1996, there was a single joint SERE school, located at Fairchild AFB near Spokane, Washington. Normally a student attends prior to arriving at his first squadron assignment.

Into the FleetBy now, officers intending to fly for the sea services have been in the military for something over two years and are ready to pass the final hurdle before they begin to repay the million-dollar investment the taxpayers have so far put into their careers. This is their final certification in a Fleet Readiness Squadron (FRS), which teaches the specific skills necessary to operate each type of Navy or Marine Corps aircraft. During the FRS rotation the Navy teaches its Naval aviation professionals the skills that will make them dangerous out in fleet units. Under the supervision of the FRS instructor pilots (IPs), the new NAs and NFOs learn the tactically correct methods for employing the weapons, systems, and sensors of their community’s aircraft. The IPs themselves, normally very skilled airmen who have completed a tour or two at sea, are the final quality check that determines whether a new aviator is allowed to go out to sea. In general, the FRS is the vessel where a particular community’s “tribal knowledge” is kept to be passed along to the nextgeneration of air crews. And at FRSs, many of the new concepts for weapons and systems are born.

26

26

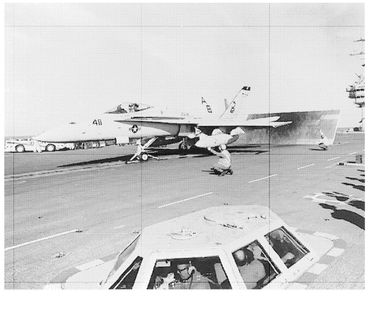

The moment of truth. A U.S. naval aviator prepares to launch in an F/A-18C on the deck of the USS

George Washington

(CVN-73).

George Washington

(CVN-73).

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

For the new NAs or NFOs, the FRS phase of their career can go quickly, or last a while. Exactly how long depends on how fast they learn to operate a fleet aircraft to the exacting standards of the FRS IPs and how soon jobs become available in one of the fleet squadrons. The more difficult aircraft like the F-14 Tomcat or EA-6B Prowler might require a young aviator to be held back so that certain skills can be reinforced; and some are “washed out” of one aircraft type and moved to another that’s less demanding.

Second Home—Squadron LifeOnce the FRS IPs have concluded that a “nugget” (rookie aviator) is ready, a call goes out to the detailing office to look for a spot in one of the fleet squadrons. Squadrons are the basic fighting unit and building block of CVWs (and of all naval aviation); and for the next ten years or so, squadron life will dominate the new nugget’s career. But before we get to that, let’s take a quick look at some Navy jargon and designations. Though the Navy is notorious for its clumsy and awkward-sounding acronyms and conjunctive designations, these batches of alphabet soup do actually serve a purpose. Consider the following table:

Naval Squadron Designations

If you understand the squadron designation, and add the squadron’s number behind it, you know what

kind

of unit you are talking about. For example, VF-14 is a fighter squadron, which just happens to fly F-14 Tomcats. They are known as the “Tophatters,” and their heritage dates back to the 1920s, when they were originally designated VF-2, flying aboard the old

Lexington

(CV-2). The system is actually quite logical and simple, if you take the time to understand it.

kind

of unit you are talking about. For example, VF-14 is a fighter squadron, which just happens to fly F-14 Tomcats. They are known as the “Tophatters,” and their heritage dates back to the 1920s, when they were originally designated VF-2, flying aboard the old

Lexington

(CV-2). The system is actually quite logical and simple, if you take the time to understand it.

Other facts about Navy squadrons are not quite so obvious; the number of aircraft and personnel within a particular kind of unit, for example. An F/A-18 Hornet squadron usually deploys with a dozen aircraft, eighteen air crew, and a support/maintenance base of several hundred personnel. Conversely, each EA-6B Prowler squadron has only four airplanes, but more air crew (about two dozen) and maintenance personnel than the Hornet unit. For each Prowler carries four air crew (compared with the F/A-18’s single pilot), and the jamming aircraft require much more maintenance than the Hornets. The squadrons themselves are structured pretty much alike. A full commander (O-5) generally commands, with a lieutenant commander as the executive officer. Backing them up are department heads for maintenance, intelligence, training, operations, and even public affairs. Watching over the enlisted troops will be a master chief petty officer, who is the senior enlisted advisor to the commander. Under normal peacetime conditions, the squadron personnel will spend about three to four years in the unit, about enough time for two overseas deployments.

Other books

Countess Dracula by Guy Adams

Stranded by Aaron Saunders

At His Mercy by Masten, Erika

Mixed up in March (Spring River Valley Book 3) by Wynter, Clarice

All That You Are by Stef Ann Holm

Complete Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

They Also Serve by Mike Moscoe

Borrowed Identity by Kasi Blake

Shadows on Snow: A Flipped Fairy Tale (Flipped Fairy Tales) by Starla Huchton