Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History (30 page)

Read Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #Imaginary Histories, #International Relations, #Great Britain - Foreign Relations - United States, #Alternative History, #United States - History - 1865-1921, #General, #United States, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #Great Britain, #United States - Foreign Relations - Great Britain, #Political Science, #War & Military, #Fiction, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #History

The first boat came up to the stone pier. The guards looked on in curiosity as the officer stepped out followed by his men. Bazalgette’s pistol appeared in the face of the sergeant of the guard as his men quickly overpowered the guards. More boats began unloading Marines. One of them carried a team of Army sappers who rushed along the stone pier to the thick iron-reinforced oak door of the main gate. They were planting their explosive charge when the small access door in the larger doors opened and an officer stepped out followed by the guard relief. The three sappers reacted quickly and bayoneted two of the guards. The officer, bolder and more quick witted than would be expected at two in the morning, pulled his pistol and shot two of the sappers. The third sapper killed the officer with a single cleaving blow of the engineer’s heavy bayonet and bolted through the open door. Another shot came from within. Bazalgette came running, followed by the fifty men who had disembarked. He saw the open door. Another shot from within echoed. He jumped over the bodies and rushed through to find two dead men on the floor and the sapper struggling with a third. A Marine rushed past to plunge his bayonet into the guard. Other men unbolted the great gate doors and pushed back the leaves. The Marines poured in.

Bazalgette and the Army sappers had carefully studied the plans of the fort that had come his way courtesy of Lieutenant Colonel Wolseley. Armed with this knowledge, the Marines fanned out through the fort as more ships’ boats unloaded the rest of the three hundred–man battalion assault force assembled from the ships of Admiral Milne’s command at Halifax. The shots had started to rouse the garrison, but sleepy, inexperienced men on a foggy night were no match for Royal Marines. Men stumbling out of their barracks were shot down or bayoneted. The Marines stormed inside. In less than a half hour, Fort Gorges had fallen. In the morning the good people of Portland would see British colors flying from it as the Royal Navy entered the port in force. The greatest port in northern New England had all but fallen. The most careful intelligence had reported that the only troops in Portland were the home guard garrisons of the harbor forts. It would all be a matter of formalities.

3

AM

, SEPTEMBER 30, 1863

For the last two days and nights, the Grand Trunk Railway in Canada had been filled with troop trains converging on Montreal, the nexus of

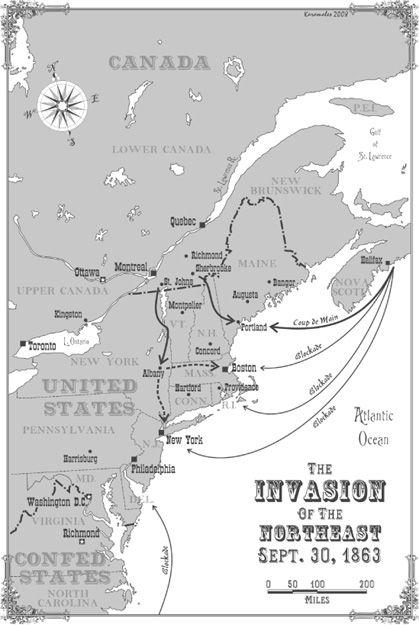

the railway’s connections with New York and New England. From the ancient site of royal France, the might of the British Empire was marshaling rapidly. Most of the forces that had been ostentatiously concentrating between Detroit and Buffalo entrained at night and sped east. The remainder, reinforced by the mobilization of the Sedentary Militia, had occupied the fortifications on the Canadian side. From Montreal the troop trains went south toward the New York and Vermont borders. Just south of St. Johns, the Grand Trunk Railway split to travel on both sides of Lake Champlain and then reunite south of the lake straight down to Albany. From there both Boston and New York City were a bare hundred miles away. Another force of regulars and Canadian Volunteers had concentrated east of Montreal at Sherbrooke along the Grand Trunk and struck southeast through the sleepy small towns of upper Vermont and Maine toward Portland.

4

Wolseley walked the platform at the railroad station as the troop trains sped through south. Already the lead elements of the invasion of New York had crossed the border and seized the first American stations, brushing aside the militia units that had been called up a few days before and cutting the telegraph wires. With the railroad in British hands the invasion forces eschewed the roads and sped south by rail through the night. This time the red-coated regiments ensured that no one would be riding ahead to alert the country that the British were coming. Washington’s eyes had been on Detroit and Buffalo, just as Wolseley had planned. The divisions they had sent north were defending borders the British had no intention of attacking. Militia and home guard units had been deemed sufficient for less threatened areas, the very places the British invasion force was pouring through as fast as their trains would take them. A few Maine regiments were to return home to recruit, he learned in the last week, but they would be dispersed across the state and of little military value.

There were any number of British generals and full colonels leading their men in the first invasion of the United States since 1813, but it was Lt. Col. Garnet Wolseley who had been the brain and energy behind the plan they were executing. Wrapped in his greatcoat against the deep chill of an early Canadian fall, he expounded to the eager clutch of staff officers around him. “We will strike Brother Jonathan so hard that it will drive any thought of attacking Canada right out of his head.” It was exciting to be a part of the exercise of England’s might against an upstart power, but in the presence of a true charismatic leader, the experience was intoxicating. Wolseley went on, more to fill the time than to elucidate. All he could do now was to wait for the first reports of the execution of his plan to deliver such a blow that Union morale would crack wide open.

He continued, “By seizing Albany and Portland we accomplish four essential objectives. First, we are too weak to defend, so we must attack. They cannot threaten Canada if they are threatened in their heartland. Second, by seizing Albany, the capital of New York, we disrupt the richest and most powerful of their states and threaten their greatest port. Third, by seizing Portland and the rest of Maine, we eliminate a geographical salient between Canada and the Maritimes, detach an entire state from the Union, and add it as a buffer to the Maritimes. Fourth, at the same time we acquire the use of another first-rate port south of overburdened Halifax from which the Royal Navy can base its blockade.”

5

He struck his fist into his open palm, letting the pop of cold leather on leather punctuate his exposition. “Gentlemen, we are on the verge of the greatest war to take place in our time. Mark me—it will dwarf the Crimea and the Sepoy Mutiny. For those of you who think promotion slow, your troubles are about to end.

“There’s another thing, gentlemen. You will find man shooting is the finest sport of all; there is a certain amount of infatuation about it, that the more you kill the more you wish to kill.”

6

Privately he admitted that they would have “toughish work of it.” The Americans would not be an easy victory. They had too much experience after two and half years of war, and they were not shy about fighting vast, bloody battles.

7

That was why audacity had to be thrown in the scales to redress British America’s geographical vulnerability. Audacity, yes, aided by indirection. The Americans must be so distracted by fires at the back of the house that they would not be able to give full attention to his breaking down their front door.

As to the front door, so audacious a plan could never have been attempted if the invasion had been on foot and horse. It would take a week of unopposed marching to reach either objective. The use of trains in the offensive had never been tried before. Trains had been used to rapidly move armies to their staging areas but never as the spearhead of invasion itself. It was the only way to deliver a knockout punch. If the element of surprise was maintained, a very big “if” indeed, then they would seize both cities by the next day. If not, they would detrain where necessary and press on by road. Maj. Gen. Lord Frederick Paulet had

been given command of the twenty thousand men of the two mixed British-Canadian divisions, designated the Albany Field Force, that would strike for New York’s capital. The Guards Brigade was in the lead trains heading south to Albany. They had to be given pride of place in this operation. While the guards had burnished their battle honors in the Crimean War, they were not known for their dash or the quick thinking of their officers. Wolseley would have been happier with some of the scrappier line regiments with less social standing in the lead.

Those regiments were heading toward Portland.

AM

, SEPTEMBER 30, 1863

George Grenfell adjusted his cap in the mirror and took a moment to reflect how far he had come since he had set off for a life of adventure. His thoughts fled back to his days in the Moroccan Rif when the bloom of youth was on him. Now his hair was white, but he told himself, “Damned distinguished. Life’s not done with me yet.”

John Hines was not so reflective. The wiry, little man had already put on his uniform and not once glanced in the mirror. He was spinning the cylinder on his pistol to make sure its action was still smooth. He spared a glance to Grenfell. “I swear, sir, you look the dandy, but find the time to admire yourself when we don’t have a fight to start.”

Grenfell just smiled and ran his fingers under his fine, white mustache. “Now, Captain, you must allow yourself to savor a splendid moment. You never know when it will be your last.”

“I’ll do that when the war is over.”

Grenfell did not reply that too many men never lived that long.

There was a knock on the door. They stopped still and glanced at each other and then toward the door. The last ten days had made them wary. That damned Major Cline and his band had dogged their heels far too closely. At times they despaired that their plan would disintegrate as Cline picked apart the pieces. Had he done so already? They had escaped him only by a hair on more than one occasion.

Another knock followed by a muffled, insistent voice. “We’re ready.” Hines relaxed. Even through the door, he recognized Jim Smoke’s rasping voice. Hines let him in, and immediately the room filled with the big man’s menace. “We’re ready,” he said again. “My men are all in place.” Two hundred Copperheads were lying in wait around Camp Morton, the sprawling Confederate prisoner of war facility on what had

been planned as Indianapolis’s fair grounds before the war. Three thousand veteran soldiers of the Confederacy were sleeping inside, or so their guards thought. Word had come to them just hours before to be awake and alert this night. Not that the guards would have picked up anything out the ordinary. The experienced regiment that had been the camp’s guard force had been transferred a week ago, their place taken by volunteer home guards. The new men were profoundly unaware of their duties.

8

AM

, SEPTEMBER 30, 1863

The city of Portland sits on a boot-shaped peninsula with the toe pointing northeast to the broad Casco Bay, sheltered from the Atlantic by a string of islands. Its harbor lay on the southern, or under side of the boot and made Portland one of the finest deep-water ports on the East Coast. The instep and big toe curled around Back Cove. The Fore River ran down the back of the foot and past the heel into the harbor. The town of some forty thousand souls occupied the peninsula from the toe to the heel. The Grand Trunk Railroad ran north to south down the western edge of the boot and curled east along the harbor to pass through the city’s Union Station and then ran north to Canada again. Most Maine men remembered the cool green lushness of the city whose every street but the smallest was lined with stately chestnuts and maples, earning Portland the title of the “Forest City.”

For the Maine men arriving from the Army of the Potomac, the station meant hot food and coffee on a chilly morning from the attentive ladies of the Sanitary Commission who maintained a permanent facility to attend to military personnel in transit. Portland was not on a main troop transit route and the facility was small, but the people of Portland had turned the entire train station into a reception center for their heroes home to rest and recruit back their strength. Since midnight the trains had been arriving, not with a few Maine regiments but with Maine’s entire military contingent from the Army of the Potomac. Sharpe’s suggestion had started the ball rolling, and that ball had rolled right over Major General Meade’s loud protest to lose all his Maine regiments—3,241 men divided into one cavalry, ten infantry regiments, and three artillery batteries. Maine had taken 3,721 men into the battle of Gettysburg and lost 1,017. Since then hundreds of wounded and missing had returned to duty, but most of the regiments had been severely

depleted even before Gettysburg. Had they been at full strength, the entire contingent would have numbered almost thirteen thousand men. It was an example of what wastage the Army had suffered in camp and in the field and of the failure to establish a regular replacement system (see

appendix A

).

9

Thus the story that they were returning home to recruit was entirely plausible. As a cover story, the public announcement had indicated only three regiments were returning. The governor had only been informed of the true extent of the troop movement the day before. The ladies of the Sanitary Commission had had to scramble, but when the trains began to arrive, they were ready with tables piled high with food and enough hot coffee to float a monitor.