Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History (29 page)

Read Britannia's Fist: From Civil War to World War: An Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #Imaginary Histories, #International Relations, #Great Britain - Foreign Relations - United States, #Alternative History, #United States - History - 1865-1921, #General, #United States, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #Great Britain, #United States - Foreign Relations - Great Britain, #Political Science, #War & Military, #Fiction, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #History

Unknown to Spencer, he had already taken a good part of Albion’s revenge. John Winslow was dead on his own quarterdeck, cut in two by a 32-pounder shot. The ship was drifting, engines dead, masts shot through or hanging shattered over the side. Its hull was riddled and taking water, its decks were a ruin, half its guns out of operation, and the dead and dying strewn across the wreckage. The two heavier British frigates were closing, their guns tearing the guts out the ship, and they were taking everything the surviving Dahlgrens could throw. The senior officer aboard

Kearsarge

was now Lamson. From

Dauntless

an officer called through a megaphone, “Do you strike,

Kearsarge

? Do you strike?”

“Fuck you, you Limey bastard!” a seaman shouted back, waving his fist. Lamson looked up to the quarterdeck and only then realized just the dead occupied it. “Do you strike,

Kearsarge

?” came again from

Dauntless

. If any man had the ability to take in a situation at a single glance and cut to the heart of it, it was Lamson. A glance at the

Topaze

saw the

Aleksandr Nevsky

cutting across the British frigate’s bow and raking her with the larboard battery. She had come to join the fight after leaving the

Gannet

adrift and burning. The Marine sergeant, his head bandaged, reported to Lamson. “Sergeant, it’s time for the Marines to be infantry. Use your Spencers to kill everyone on that deck.”

Turning back to the

Dauntless

, he cupped his hands and bellowed, “Double canister! Double canister, sir! That is my answer!” He sensed what was coming next, could see with his mind’s eye the

Dauntless

’s gun deck crews climbing the ladders to the decks armed with pikes, cutlasses, and pistols to board. “Prepare to repel borders!” he shouted again.

Dauntless

lurched closer; the men massing on her deck were visible. Among the blue jackets and their pikes were the red coats of the

Royal Marines, their Enfields with fixed bayonets. Lamson’s Marines rose from their concealment and fired their repeaters into the packed crowd as bodies pitched forward over the side or backward into the crowd. “Sergeant! The carronade!” Lamson grabbed him by the arm and pointed at the fat, blunt gun on the

Dauntless

’s forecastle. This naval shotgun would sweep his deck with musket balls. The sergeant dropped the gunner with a single shot and then with a smooth cocking of the handle, he shot the next man who grabbed the lanyard. By then his men had dropped the rest of the gun crew.

32

Dauntless

was now a bare yard away, and the British were still massing on the side. The forward XI-incher swung on its pivot to point at a sharp angle down the side of the enemy ship. The British were flexing their legs to make the leap from their greater height as the ships closed that last yard when the gun captain yelled, “Fire!” The gun leapt back on its lines, spewing two large tins of small iron balls into the crowd. The ships ground against each other. The remaining members of

Gettysburg

’s crew raced up the ladders to repel borders, but there was only silence from the British ship. They watched the blood pour out of the

Dauntless

’s scuppers onto the

Kearsarge’s

deck and then cascade out of the wreckage as the British ship drifted away, leaving a pink stain in the water.

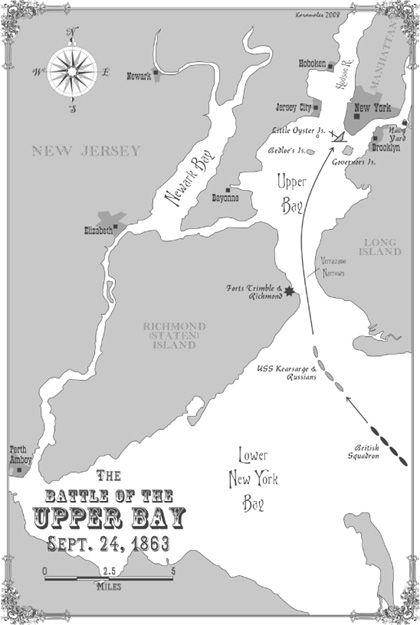

From this moment, the

Kearsarge

became only a spectator to the last stage of what would be called “the Battle of the Upper Bay.” The

Topaze

and the

Nevsky

continued to throw broadsides into each other, with the

Topaze

clearly getting the upper hand. The

Peresvet

was locked in a slugging match with the smaller but deadly

Alert

. Time had run out for the British. A swarm of harbor defense gunboats were steaming down the East River from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Alone, none of them would be a match for any of the British ships. In a swarm they could hem a larger ship in and strike from any direction. The end was inevitable, especially since more powerful warships were also coming to their aid. The first of them was the

Oslyabya

, rushing to Lisosvky’s aid.

Captain Spencer was no romantic; he knew when the game was up. He did take intense satisfaction to see the

Kearsarge

listing badly from the water rushing in through the colander that was her hull. She would go down and soon. His mission was all but accomplished. Now Spencer must save what he could. He signaled the

Alert

and

Dauntless

to break off action and steam for the Verrazano Narrows and escape.

Gannet

was adrift and in flames.

Dauntless

limped south escorted by

Alert

. Running the gauntlet of the forts at top speed

Topaze

and

Alert

made it through with heavy damage.

Dauntless

’s slowness was her doom as the shot and shell from the forts hailed down on her. Slowed even more, she was caught by

Oslyabya

and the gunboats and pounded to pieces. She refused to strike and went down fighting.

33

As Lamson watched the battle recede, the surviving engineer reported the damage below. The ship was taking water too fast. The pumps had been destroyed with the boilers. A gunboat came aside and asked if

Kearsarge

needed assistance. “I need a tow to the Navy Yard before I sink,” he called over. It would be close. The ship was settling fast.

34

AM

, SEPTEMBER 24, 1863

The Foreign Office special courier was rushed into the office of Ambassador Lord Lyons. He knew what news the courier brought, and it confirmed his worst fears. After Moelfre Bay, it could only be war. He imagined the news had spread immediately from the ship to the docks and must at this moment be flying through Washington.

Lyons called for his secretary and instructed him to personally request an interview with the Secretary of State. Then he carefully examined his instructions.

The halls of the State Department were crowded when Lyons entered just before two in the afternoon. The whispers that announced his identity silenced the crowd but did not quell their angry looks or the occasional hiss. Wretched manners, these Americans. He was ushered through open doors directly into Seward’s office. Seward was facing the open window, hands clasped behind his back. He cut such a slight figure, but when he turned he seemed to grow from the anger in him.

Lyons did not betray his concern as he bowed. “Mr. Secretary, it is my sad duty to inform you that as of September 10 a state of war has existed between the British Empire and the United States of America.” He went on to describe the justifications of Her Britannic Majesty’s government for taking these much-provoked steps, reading from his instructions the precise language directed by the Foreign Office. When he had finished, he bowed once again and presented the declaration to Seward.

35

“Lord Lyons, is it the custom of Her Majesty’s government to attack before delivering its declaration of war? Even for Britain, that is a new and yet unfathomed perfidy.”

“Attack, Mr. Secretary?”

“Lord Lyons, don’t play games with me!”

“I assure you, sir, that I do not understand what you mean.”

Seward’s skinny face had flushed red. Lyons could not help thinking that with his shock of unruly white hair and great Roman nose, he looked nothing more than a fighting cock ready to strike. “The telegraph from New York has been on fire for the last two hours with news of a great naval battle in New York Harbor. A British fleet pursued a U.S. warship escorted by two Russian ships into the Upper Bay in a running battle that rages as we speak.”

Lyons blanched. He was aware from his instructions that a squadron had been sent in pursuit of

Kearsarge

, but not in his wildest imagination did he dream that they would hunt their prey into the heart of America’s greatest city, much less than it would happen before the formal declaration had been delivered. He could only keep an impassive face and hand Seward his letters.

Seward snatched them from his hand. He spat on them, threw them on the floor, and ground them into the carpet with his heel. Looking directly at Lyons, whose eyes had gone wide at the act, he said to his aide, “Show this gentleman out the back door.”

36

PM

, SEPTEMBER 24, 1863

As soon as Lisovsky’s ships docked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard they offloaded their wounded into the eager arms of ambulance crews. Mayor George Opdyke immediately saw to the provision of a train to take Lisovsky to Washington shortly after the admiral had broken the seal on his orders, written in the hand of the Czar himself, and read them. The progress to the station had been impeded by the huge crowds of cheering New Yorkers, hailing the savior of their city from British surprise attack. As the police cleared the way to the station entrance, a police captain ran up with a telegram and thrust it into the mayor’s hand.

Opdyke’s face turned white. He handed it to the admiral and stood up to wave the crowd silent. “Good people of New York, I have just been handed a telegram from the President of the United States.” The buzz of the crowd hushed in expectation. “I am informed that today, as the battle raged in the Upper Bay, the British ambassador delivered a declaration of war.” He paused for the impact to sink in. The silence held, then burst into a wave of anger from thousands of voices that grew into a howl of incandescent rage.

The tracks were cleared for the train’s run all the way to Washington. Ambassador Stoekel and a naval guard of honor were there to greet

it. The ambassador and he spoke quietly before the Russian party climbed into their waiting carriages with a cavalry escort to lead the way. Crowds had gathered at the news of Lisovsky’s approach and broke into wild applause as he sped to meet Lincoln and Seward.

They were immediately ushered into Lincoln’s private study. Stoekel had never seen two graver men than Lincoln and Seward. He introduced Lisovsky, and after warm greetings, Lisovsky bowed and recited the orders Czar Alexander had written him. “Your Excellency, my Imperial Majesty has instructed me that in the event of an attack by a foreign power, particularly Britain or France, upon the United States or upon the recognition of the Southern Confederacy by either of those powers, I am to put my squadron at the disposal of Your Excellency. I have three frigates now in New York. Two more corvettes and a clipper are expected within a few days. I am also instructed to say that a squadron of the Imperial Navy will shortly be arriving at the port of San Francisco under the same orders. I am at your command, Your Excellency.”

37

Stoekel now spoke. “Mr. President, I am instructed by His Imperial Majesty under contingent orders that should the United States be attacked by these powers, I am to confirm the admiral’s orders and state that upon notification of such an attack His Imperial Majesty will declare war on the attacker. I am empowered to conclude a treaty of alliance at once.”

38

.

A Rain of Blows

AM

, SEPTEMBER 30, 1863

The British sailors pulled slowly on their muffled oars through the fog. They had left the iron screw troopship HMS

Dromedary

some distance back. In the boats between the oarsmen sat Royal Marines, still and silent. In their blue greatcoats and shakos and with the Enfield rifles in their hands, they could easily be mistaken for American troops, especially in the thick fog.

A light, wan and struggling against the fog, appeared ahead. A clutch of guards, wrapped in their own greatcoats against the chill and huddling against a fire in an iron basket, could be made out under it. At last one cried out, “Who goes there?”

“Garrison relief,” answered a voice in a good New England accent.

“Come in, then,” answered the guard. Capt. George Bazalgette, the officer of Marines, sighed in quiet relief. They had surprise on their side. He silently thanked Providence that the worsening situation had snatched him out of the back-of-beyond station on San Juan Island on the Pacific coast south of Vancouver after the aborted confrontation between Britain and the United States dubbed “the Pig War.” An assignment like this was bound to ensure that he was not remembered as the officer who almost fought in the Pig War.

1

The plan had relied on the laxness of the Maine home guards who provided the garrison of the fort on rotation. The huge fort appeared as a shadowy mass in the fog. The officer had seen it before on a special visit he had made in mufti a week before. Build on a man-made island on Hog Island Ledge, it was a granite-built, six-sided fort with two tiers

of casemates, designed for 195 guns, at least half of which had been installed.

2