Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (37 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

The Peasants’ War began in the autumn of 1524 as a series of disturbances in the southwest of Germany, in the Black Forest, around Lake Constance, and in Alsace. In itself, this sort of rural uprising was nothing new. The German peasantry was suffering considerably from worsening economic conditions, exacerbated by a sustained effort to restore onerous conditions of labor service (even serfdom) that had been relaxed as a result of the chronic labor shortage in the period following the Black Death. These grievances had provoked a series of local disturbances in the half century before the Reformation, known collectively as the

Bundschuh,

after the heavy peasant boot chosen as a banner of solidarity. In 1514 there was a further serious rebellion, the “Poor Conrad,” against the oppressive rule of Duke Ulrich of Württemberg, and a rising in the Rhine Valley in 1517.

23

In this context it was not immediately clear that

the events of 1524 would be significantly different. But the peasant musters proved more numerous and more persistent than heretofore. By the early months of 1525 they had spread beyond the usual heartland of the

Bundschuh,

through Bavaria to Franconia, Thuringia, and Saxony.

B

AND OF

B

ROTHERS

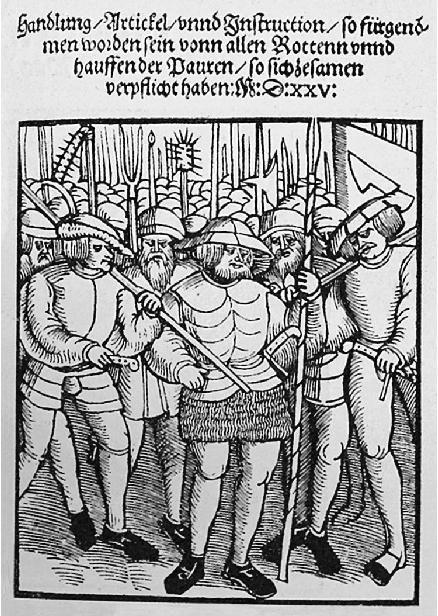

One of numerous editions of the peasant manifestos, this woodcut plays up the potency of the rebels’ military threat.

By this time it was clear that this was not simply a further spasm of pain and distress at declining living standards, but something of an entirely different order. The rebels were better organized, better coordinated, and better led. More dangerously, from Luther’s point of view, they had also begun to clothe themselves in the language of the new evangelical movement. In March 1525 members of the various peasant bands met in Memmingen to agree on a common program. The result,

the

Twelve Articles,

was in the main conventional enough, with complaints about labor service obligations, denial of the rights to cut wood in forests or trap game, high rents, and the seizure of common land. But it also included a demand that pastors should be elected by their own congregations, a common thread in many of the urban Reformation conflicts unfolding in precisely these years. Most incendiary of all was the fact that the whole document was clothed in evangelical theological language, with copious marginal scriptural citations.

Third, it has until now been the custom for the lords to own us as their property. This is deplorable, for Christ redeemed and bought us all with his precious blood, the lowliest shepherd as well as the greatest lord, with no exceptions. Thus the Bible proves that we are free and want to be free. . . .

Twelfth, we believe and have decided that if any one or more of these articles is not in agreement with God’s word (which we doubt), then this should be proved to us from Holy Writ. We will abandon it, when this is proved by the Bible.

24

This added fuel to the flames, and certainly seemed to vindicate those who claimed that the insurrection was the inevitable consequence of the challenge to existing authority raised by the evangelical conflicts. The assumed author of the

Twelve Articles,

the furrier Sebastian Lotzer, had no direct connection to Luther, but two of the black sheep of the Wittenberg movement, Andreas von Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer, were soon deeply embroiled. Karlstadt we have met; his entanglement with the revolt seems to have been a largely unintended consequence of his preaching of the radical gospel in Orlamünde. Müntzer was a problem of an altogether different order. In 1519 he had been an early and aggressive advocate of Luther’s movement; in 1520 he preached in Zwickau, on Luther’s recommendation. But by 1522 the two men had fallen out. Müntzer was a man of great talent, as was revealed by his German Evangelical Mass of 1524, an imaginative prototype for a

vernacular evangelical service.

25

But he was also willful and undisciplined. His incendiary sermons and increasingly direct attacks on the Wittenberg leadership led in 1524 to his deposition from the church at Allstedt. When Müntzer resurfaced at Mühlhausen, he was again expelled; but returning at a critical juncture when the town had effectively thrown in its lot with the rebellious peasants, Müntzer soon emerged as one of the most powerful spokesmen of the insurgency.

This uncomfortable turn of events exposed one of the other salient aspects of the Peasants’ War: that it was by no means confined to the countryside. The earlier

Bundschuh

revolts had exposed significant tensions between city dwellers and the inhabitants of the rural hinterland; the roving peasant bands were for the most part feared and despised.

26

But the Peasants’ War came at a moment when many towns were already experiencing significant social tension as a result of the Reformation—debates and disputes that set portions of the citizenry against the civil leadership. Here the appointment of clergy, either favorable to the evangelical message or more conservative, was a significant flash point. The new stirs appeared to many in the towns an opportunity to press home their advantage. Alongside the

Twelve Articles

a number of the most important manifestos issued during the revolt were drafted by urban rebels.

27

These, like the

Twelve Articles,

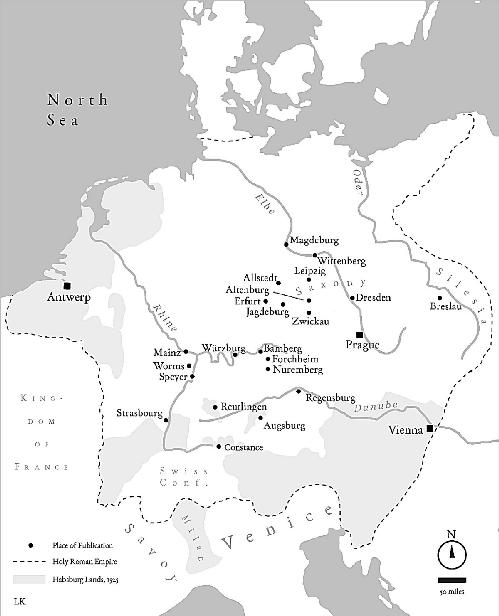

were widely circulated in print. This use of print represented the final, decisive shift in the nature of the revolt: print became the instrument for molding a national movement, and, in the process, exposing the radicalism of the peasant demands to friend and foe alike. For Luther there was a certain rough justice that the same medium that had brought him to national prominence was now used to broadcast and amplify what he could only see as a frightening perversion of his evangelical message. The key writings that accompanied the Peasants’ War were published widely throughout Germany. The

Twelve Articles

of Memmingen went through multiple printings, from Strasbourg and Worms in the west, to Augsburg, Regensburg, and Constance in the south. In the northeast they were printed at Zwickau and Leipzig, Erfurt and Magdeburg; this, for Luther, was dangerously close to home. Müntzer briefly ran his own press in Allstedt; the

Frankfurt Articles

of April 1525 were also widely circulated.

28

All in all around eighty-five editions of the peasant manifestos and Müntzer’s writings proclaimed the case for reform; and their allegiance to a social gospel inspired by Martin Luther.

T

HE

B

ITER

B

IT

Printing locations of manifestos of the Peasants’ War and other associated publications.

This was potentially enormously damaging, particularly when the peasant bands turned on their persecutors and began to sack noble castles and fortified houses. Religious houses also felt the force of their antipathy (many peasants paid their rents to clerical landlords). Luther had been initially slow to react to the stirs in the distant Danube basin. With the publication of the

Twelve Articles

he recognized the need to respond, but he did so with a measured evenhandedness that satisfied no one. In his

Admonition to Peace

he naturally condemned the disorder and violence. But equally he warned the princes: in a dangerous sentence he lectured them that the rebellion was also a just punishment for their sins. Their resistance to the Gospel and exploitation of the common man was the cause of the revolt. Only repentance could divert God’s wrath.

29

Conventional perhaps, but incendiary; the result was that Luther’s first comment on events disappointed both sides, while giving some encouragement to the sentiment that the peasant grievances were justified.

This was, it must be said, an exceptionally difficult period for Luther. Events seemed to be crowding in a torrent of negative headlines: Erasmus, Karlstadt, and Müntzer, the Peasants’ War, the abusive reactions to his own marriage. While we can separate these different issues into neat compartments, in the day to day of spring and summer 1525 this must have seemed to Luther like a perfect storm of ceaseless bad news. Luther was perfectly aware that his enemies interpreted this as the wholly predictable denouement of the crisis induced by his own disobedience. It did not help that in precisely these months Luther was having to deal with the transition of authority in Electoral Saxony following the death of Frederick the Wise in May. The relationship between Luther and his first and most crucial patron had been a strange one, but his passing at such a difficult moment left little time for reflection and mourning. In the event, Frederick’s successor, his brother John, was even more resolute in his support for the Reformation. But this fact (which would have been clear from Duke John’s earlier support for Luther) did not stop speculation that Luther’s writings against the peasants were inspired by a wish to cozy up to the Catholic Duke George now that his great

protector was gone. “They say publicly in Leipzig that since the Elector had died, you fear for your skin and play the hypocrite to Duke George by approving of what he is doing.”

30

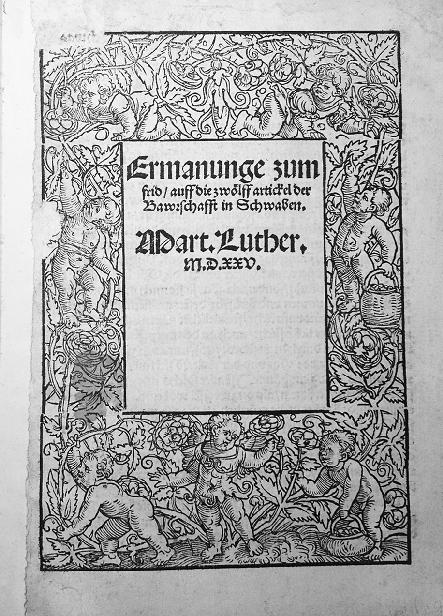

ADMONITION TO PEACE

Too little, too late. In 1525, unusually, Luther failed to find the words to articulate a coherent response to the uprising.

Luther’s enemies were circling, and his friends were nervous. As had now become characteristic of Luther, his reaction was both belligerent and deeply personal. In April and May he visited relatives in Eisleben. Naturally he received invitations to preach, but his reception was very different to what he had come to expect. The atmosphere was aggressive; the congregation rang bells to signal their dissent. Luther had

experienced a similar defiance when he tried to bring order to Karlstadt’s former congregation in Orlamünde. Here members of the congregation had openly contested his teaching. Later he was helpfully informed that members of the Orlamünde congregation were using his tract

Against the Heavenly Prophets

as toilet paper.

31

When Luther had elaborated his concept of the priesthood of all believers, this was not at all what he had in mind: this was anarchy, the dissolution of social order. Returning to Wittenberg through Weimar Luther was left in no doubt by Duke John of the gravity of the situation: the princes now demanded his allegiance.

This was the background for the most notorious of Luther’s works,

Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants

. This had been intended initially as a new third section for the third Wittenberg edition of the

Admonition to Peace,

a context that would have diluted significantly its stark message of retribution. But for the printers, this grim, sustained, remorseless denunciation of the violence was irresistible: it was published as a separate pamphlet and massively printed around Germany. Here, an audience who had perhaps never met this side of Luther could read his bleak verdict on the consequences of rebellion: “Therefore let everyone who can smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you, and a whole land with you.”

32