Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (36 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Yet it was Erasmus’s fate that at this point his admirers, and those of the Wittenberg reformer, largely converged. When a friend sent Erasmus two of Luther’s early works in December 1518, he assumed that Erasmus would approve of what he read.

8

In March 1519 Erasmus received a delegation of German admirers who had traveled from Erfurt and Wittenberg to meet him. They brought with them a letter from Martin Luther, the first indeed that passed between the two men. Erasmus replied with cautious courtesy, but the exchange of compliments masked a growing sense of unease.

9

Erasmus was happy, as were his followers, to concur with many of Luther’s criticisms of church practice and ceremonies. The critics of indulgences included many humanist scholars. But the escalation of Luther’s defiance, his growing alienation from the church hierarchy, and the increasingly strident language of his denunciation of the papacy all filled Erasmus with alarm. He could see that they were men of very different temper. Furthermore he feared that his own more measured reforming agenda, characterized as so often in the humanist community by wit and irony rather than a direct challenge, might be tarnished by association. The Luther affair became an increasing preoccupation: on the part of those friends urging Erasmus to speak out for Luther and those warning that Erasmus’s enemies were seeking to tar him with the same brush. Wolfgang Capito was among those pleading with Erasmus for restraint: “There is nothing [Luther’s] enemies wish more than to see you indignant with him.”

10

Erasmus attempted to find a middle way: to signal sympathy for Luther while withholding support. In a careful letter to Frederick the Wise, Erasmus refused to be drawn into a theological discussion. Instead he took aim against the immoderation of those who condemned the Wittenberger. “One would think they thirsted for human blood rather than the salvation of souls.”

11

This formula, that Luther deserved to be heard rather than condemned, was one that Erasmus would hold to

through the critical years when Luther’s cause was debated in Germany and Rome, and one that earned him considerable opprobrium from the papal party.

12

Luther, for his part, reckoned that he had got Erasmus’s measure. He was an early reader of Erasmus’s New Testament, and had a copy of the Basel edition in his hands soon after its publication in March 1516. He rejoiced in Erasmus’s denunciation of clerical hypocrisy: “he trounced the religious and the clergy so manfully and learnedly, and had torn the veil off their out-of-date rubbish.” But he also recognized that the two men came to their views of contemporary church questions in very different ways: “How different is the judgment of the man who yields something to free will than one who knows something of grace.” His conclusion was harsh: “I see that not everyone is a truly wise Christian just because he knows Greek and Hebrew.”

13

Nevertheless Luther reached out, because he realized that the movement would be stronger if the two were not seen to be at odds. And for a time this was certainly the case. In the first difficult years Erasmus’s interventions were more helpful to Luther’s cause than the opposite, as Luther would grudgingly acknowledge. “Some people had in hand a magnificent letter of Erasmus to the Cardinal of Mainz. [Erasmus] protects me quite nobly, yet in his usual skillful way, which is to defend me strongly while seeming not to defend me at all.”

14

In particular Erasmus made one crucial intervention when Frederick the Wise consulted him for his opinion when their paths crossed in Cologne in November 1520. This was Erasmus’s chance to damage Luther had he so wished, in a private conversation with Luther’s indispensible protector. But whatever his irritation at the difficulties Luther might be causing him, Erasmus was surprisingly supportive. Even at this relatively late stage in Luther’s process (the bull

Exsurge Domine

had already been published), Erasmus was prepared to aver that good men and lovers of the Gospel were those who had taken the least offense at Luther. “[T]he whole fight against Luther sprang from hatred of the classics and from tyrannical ignorance.”

15

All of this changed with Luther’s condemnation at the Diet of

Worms. However much he regretted the virulence with which Luther had been pursued, Erasmus knew he could not follow him into schism. Already he was extremely concerned that his own reputation would be dragged down with Luther. In a letter of August 1520 he frankly asked Luther not to involve him in his business. Luther agreed to respect his wish, though not without a certain bitterness. Erasmus, he had concluded, “was not concerned for the cross but for peace. He thinks that everything should be discussed and handled in a civil manner and with a certain benevolent kindliness.”

16

This appraisal was one with which the great humanist would probably concur. He understood his own temper all too well. In an unusually frank and revealing letter to an English friend, Richard Pace, he confessed as much.

Even had all [Luther] wrote been religious, mine was never the spirit to risk my life for the truth. Everyone has not the strength needed for martyrdom. . . . Popes and emperors when they make the right decisions I follow, which is godly; if they decide wrongly I tolerate them, which is safe.

17

Erasmus now came under increasing pressure to denounce Luther publicly. For some years he resisted, with charm, evasion, and sophistry; but in the end the pressure would tell. By 1524 it had become clear that he would write against Luther; rumors that something was in the wind reached Wittenberg, prompting the reformer to write directly to ask Erasmus to hold back.

18

Luther was to be disappointed: the pressure on Erasmus to act was by this point irresistible. But if the breach between the two men was to become public, Luther heartily approved the choice of a battleground. Erasmus chose to address the issue that defined the difference between the two men, theologically and temperamentally, as Luther had recognized since 1516: Luther’s denial of human agency in the act of salvation, the doctrine of justification by faith.

L

UTHER,

E

RASMUS, AND THE

C

OMMON

M

AN

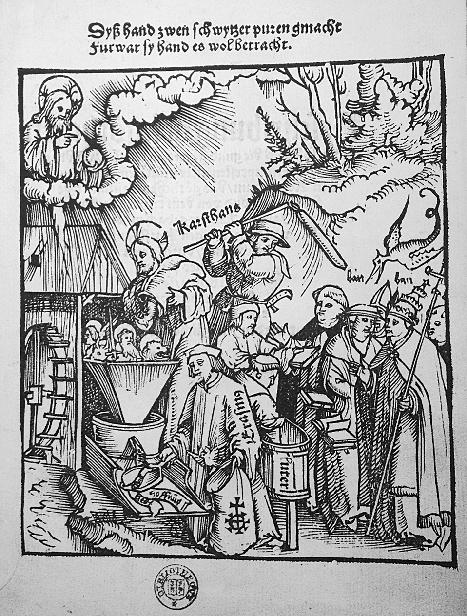

In this famous image, Luther and Erasmus are depicted as allies in the cause of reform, harvesting the word of God from the “host mill.” Note the peasant with his flail, preparing to chastise the churchmen who reject the word.

De Libero Arbitrio,

Erasmus’s

Diatribe or Discourse Concerning Free Choice,

was published in September 1524. It is a careful, thoughtfully constructed, and in many ways humane consideration of the central problem of Reformation theology. Erasmus recognized that without grace there was no hope of salvation; but here lay the paradox, for without freedom surely man could not be held responsible for sin. Luther’s theology, to Erasmus (and many Christians since), required one to discount all good works, merit, and obedience. Surely a righteous God would reward good deeds? Although grace initiated salvation, if it did

not require man’s free cooperation, then God was responsible for evil—a bleak prognosis indeed.

De Libero Arbitrio

achieved considerable success. Especially among the scholarly theological community of Germany it was widely read, with editions in all the main centers of printing in the Empire, with the exception of Wittenberg.

19

Erasmus observed the necessary courtesies, ensuring that it would be known in Wittenberg by sending a copy to Melanchthon. It was immediately obvious that Luther should reply. He read the book almost immediately, though with characteristic disdain (“an unlearned book from such a learned man”). Yet it would be another eleven months before Luther settled to the task, and a further five before the work was finished: his response,

De Servo Arbitrio,

On the Bondage of the Will,

appeared from the press of Hans Lufft only on December 31, 1525.

20

This was distinctly odd for such an experienced and accomplished disputant. When one considers that Luther was here defending the theological core of his movement, the issue that had divided evangelical and humanist approaches to reform since the beginning of the Reformation, it becomes even more so. One must acknowledge that Luther had other pressing preoccupations, particularly in the urgent need to contain the fallout of the Peasants’ War. But there was more to it than this. Some part of Luther seems to have felt that Erasmus was not worth the trouble: as he rather rudely expressed it in his reply, if such a great intellectual could do no better than this, it only confirmed his view that free will was a fiction. It was only his friends’ insistence that Erasmus’s work was achieving traction among supporters of the Reformation that forced Luther to engage.

The result was a crushing, comprehensive restatement of Reformation doctrine. At four times the length of Erasmus’s original, it ranged widely and was severe on what he perceived to be his opponent’s naive and superficial (if plausibly attractive) restatement of human agency. Luther set out his position with brutal clarity. It was not possible for a person to turn to God. Conversion was God’s promise and gracious act, and

from this there could be no stepping back. Only the elect fulfilled God’s will; as far as salvation and reprobation are concerned, human will could determine nothing. Luther is here the master theologian, rebuking a well-meaning but lazy amateur for a lack of serious engagement with theological truths. The engaging brevity of Erasmus’s work is here turned against him.

Erasmus, as was so often the case, took great offense at this personal criticism. His first reaction (also characteristic) was to try to shut Luther down with a behind-the-scenes maneuver, in this case appealing to the new Elector John to reprimand Luther for this insolence. The elector forwarded the letter to Luther, and followed his advice to stay out of the quarrel. Erasmus also took it into his head that Luther had attempted in some way to pull a fast one, and that the publication was timed to prevent him from being able to reply before the spring Frankfurt Fair. This is surely fantastical: had this been the case Luther would have delayed two more months; in any case Luther hardly needed to play this sort of game. One way or another Erasmus was determined that Luther should be answered at the March fair. In contrast to the painful deliberation of Luther’s

Bondage,

Erasmus tossed off the first part of his reply,

Hyperaspistes

(the “protector” of the

Diatribe

), in ten days. Froben was persuaded to clear most of his presses to have the work printed, and the task was duly accomplished in time for the fair.

21

Although this makes a good story, and a fine demonstration of Erasmus’s command of the printing process, this seems to have been a private competition with only one participant. Luther had little further interest in sparring with the great humanist; he was sent a copy of the

Hyperaspistes

by Philip of Hesse but was in no hurry to read it. By September it was clear that he would not reply. Erasmus had raised the temperature by responding in kind to Luther’s personal abuse, but had not advanced the theological debate in any meaningful way. Although the

Hyperaspistes

was a publishing success, it was probably more for the spectacle of Luther and Erasmus at each other’s throats than for its contents.

22

Erasmus published a second part of the

Hyperaspistes

in September

1527, generally agreed to be dull and rather listless. By this point Luther had moved on. He would, interestingly, continue to read Erasmus in later life. He was keen to obtain the revised 1527 edition of Erasmus’s New Testament, and his copy is heavily (if critically) annotated. Though Luther had been alarmed at the prospect that Erasmus would speak against him, the controversy when it came did surprisingly little damage. Those humanists who had been attracted to Luther’s cause in the early years had already made their choice. Erasmus’s work gave comfort to some of Luther’s Catholic opponents, but it did little to shift opinion elsewhere. Ultimately it was a much more significant milestone in the life of Erasmus than in the Reformation movement as a whole.

THE PEASANTS’ WAR

If the conflict with Erasmus did little to damage Luther, that could not be said of the second great challenge of this crowded year, the Peasants’ War. This was a truly existential event for Luther’s thriving yet still vulnerable movement: the greatest threat to the new church’s survival since the first years of his protest.