Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (35 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

D

UKE

G

EORGE OF

S

AXONY BY

L

UCAS

C

RANACH

High principled, moral, and chivalrous, George was Luther’s most formidable opponent. Cranach was always content to take commissions from Catholic patrons; if Luther disapproved he was wise enough to keep his thoughts to himself.

Often one needs to take protestations of poverty on the part of sixteenth-century craftsmen with a pinch of salt; but on this occasion the Leipzig printing industry really was in desperate straits. Wolfgang Stöckel, a printer in Leipzig since 1493 and a true giant of the industry, had in 1508 bought a large house in the Grimmaische Strasse. In 1525 he was forced to sell it because of his mounting debts.

53

Two printers, Jakob Thanner (the printer of the ninety-five theses) and Michael Blum, tried printing forbidden evangelical literature, but were apprehended and punished. Both Nickel Schmidt and Valentin Schumann attempted to transfer to Wittenberg, and Schmidt worked there briefly as a bookbinder before returning disconsolate to Leipzig.

54

Even before he was rebuffed by Wittenberg, Schumann had something altogether more audacious in

mind. In 1522 he set up a branch office in Grimma, some fifteen miles south of Leipzig. Here his factor, Nikolaus Widemar, turned out a range of small evangelical books, works by Luther and others, including the partial editions of the New Testament already spoken of.

55

In 1523 the shop was moved to Eilenburg, again under the management of Widemar but now in partnership with Wolfgang Stöckel.

56

There was nothing ideological in this for Schumann (or indeed Stöckel); Schumann had also provided the types for the Emser press in Dresden.

57

It represented simply a desperate attempt to put bread on the table. In 1526,

to stave off financial ruin, Stöckel abandoned Leipzig and moved his operation to Dresden. A residual press he left behind in Leipzig in the hands of his son Jakob published no more than a handful of works.

58

The Grimma and Eilenburg experiments were the first example of a practice that would find several imitators in the century of the Reformation: the establishment of a surreptitious branch office in neutral territory to take advantage of a lucrative but forbidden trade. The great Antwerp publishing magnate Christophe Plantin would attempt something similar to print Protestant books during the Dutch Revolt.

59

Wenzeslaus Linck was behind the establishment of a press in Altenburg, at a time when evangelical printing was banned in Nuremberg.

60

But for Leipzig’s printers it was a sign of desperation, a Band-Aid for an amputated limb. Without the trade in Reformation books, which accounted for almost half the German book trade in these years, the presses were doomed to decline.

Leipzig’s main publishers were experienced and highly capable; they were also, as these examples show, inventive and resourceful. But they were washed away by an economic tide so fierce that they were unable to stand in its path. Demand for evangelical books was so strong in these years that it sucked up most of the spending power available for books, making it virtually impossible for Leipzig’s printers to develop alternative markets. Their attempts to do so were thwarted by Duke George’s iron determination, the weak demand for conservative theology, and the buoyancy of local rivals Erfurt and Wittenberg. Like handloom weavers confronting their first spinning jenny, the Leipzig printers could do little except gaze upon their doom, their hands tied from taking any of the actions that could have rescued their business. Duke George lived on until 1539, firmly upholding his Catholic faith. Only then would his successor move Ducal Saxony into the evangelical camp, twenty years too late for Leipzig’s printers.

9.

P

ARTINGS

N

N

J

UNE 13, 1525,

a small private ceremony took place in the Augustinian house at Wittenberg, now Luther’s home. Present were Justus Jonas, Bugenhagen, and Johann Apel, professor of law at the university, along with Lucas Cranach and his wife. They were there to witness an extraordinary event, the betrothal of a forty-two-year-old former monk to a twenty-six-year-old former nun, Katharina von Bora. Bugenhagen presided and the Cranachs acted as sponsors and witnesses. Unusually, and in the same limited company, the wedding proceeded the very same evening. Only two weeks later was there any public festivity to celebrate Martin Luther’s transition to married life.

This was in many respects a strangely subdued, almost furtive way for Luther to mark this important, and ultimately joyous, milestone in his life. The reformer was a hugely popular figure in Wittenberg, and one would have thought that he would want to take this momentous step in the company of his friends and congregation. Yet not even his loyal friend Philip Melanchthon was invited (Philip was deeply hurt, and found it hard to disguise his sense of outrage in his letters recording the event).

1

It was not as if Luther was blazing a trail in taking a wife. Most of his Wittenberg colleagues were already married, and with his full approval. He had been a consistent advocate of clerical marriage in his

writings since at least 1520. But Luther knew his was a special case. Not only was he a former monk, and his wife a runaway nun; he was also a condemned outlaw and heretic. What sort of life was Katharina taking on? And Luther knew he was handing a huge propaganda opportunity to his enemies. In the deeply personal pamphlet exchanges of the early Reformation, every aspect of Luther’s conduct was exposed to opprobrium: his vanity, his arrogance in his own judgment, his ungovernable temper. Now all was clear: the church had been turned upside down, monasteries cleared and convents emptied, so that Father Luther could satisfy his sexual appetites.

2

Luther knew all this would be said; he also knew that this would add fuel to the fire at a time when the Reformation faced a barrage of criticism from many separate quarters. Luther’s marriage came, most unhappily, at the juncture of the most serious crisis that had faced Luther’s movement since its first turbulent months. In 1524 the great humanist Desiderius Erasmus published the long-awaited attack on Luther’s theology, precipitating a complete break between the two men. Luther recognized the importance of this, but the need to craft a suitable reply had, most unusually for Luther, been repeatedly delayed, overcome by the still more serious calamity of the Peasants’ War.

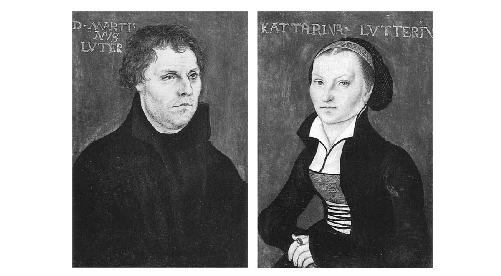

His duties as witness performed, Lucas Cranach was in the position to offer a further gift, a wedding portrait of the happy couple. This double portrait was, as was the usual custom, composed as two separate panels, which could be hung side by side with man and wife facing toward each other. The portrait of Luther is one of Cranach’s greatest works, a psychological study of great honesty. Here Luther is stripped of the polemical armor of Cranach’s first depictions of the young reformer. It shows a lean, tense figure, staring with a distracted absence into the middle distance. Gone is the confident optimism of the first years of the Reformation, the iron-willed zeal of the young monk; this is a man close to the edge of his endurance. And with good reason. For in June 1525, when Luther first took on the obligations of a family, he was confronting a challenge that might well have consumed his Reformation. Germany was in revolt, and Luther, for once, struggled to find the words to give his movement direction.

M

ARTIN AND

K

ATHARINA:

T

HE

M

ARRIAGE

P

ORTRAIT

Cranach’s powerful psychological portrait does not disguise the tension of this momentous year. Katharina looks ready for the challenges ahead.

ERASMUS

When Luther first loomed on his consciousness, Erasmus had just enjoyed the most successful years of his career. In the twelve months from August 1515 Erasmus sent to the press three works of huge significance: his editions of Seneca, Jerome, and the first recension of the Greek New Testament. These resonated throughout the European scholarly community. In 1516 friends began preparing the first collective catalog of his work; during the four years between 1514 and 1517 Erasmus would be Europe’s most published living author (a title he

relinquished in 1518 to Martin Luther).

3

Not surprisingly, Europe’s printers competed for his attention and his patronage. He had become that rare phenomenon: a scholar who could make money from writing.

Erasmus now enjoyed a towering reputation among humanist scholars across all of Europe. Especially among the humanist sodalities of Germany, Erasmus was lionized. Among those from central Europe who vied for his attention were some of those who would later be Luther’s closest supporters, among them Melanchthon, Capito, and Spalatin. Spalatin wrote to inform Erasmus that Frederick the Wise had purchased all of his published works that he could find for the library in Wittenberg. The youthful Melanchthon sent a verse composition.

4

This adulation was not, at the time, in any way reciprocal. As Erasmus shuttled back and forth between Paris, Louvain, and Basel, Wittenberg scarcely figured on his consciousness. In a revealing aside in a letter to Frederick the Wise, as late as April 1519, Erasmus apologized that he had not responded to Frederick’s respectful greeting by sending him a book, but he had, he said, no one he knew in Wittenberg to send it to.

5

The first mention of Luther in the great humanist’s correspondence is strangely oblique. In December 1516 Spalatin had written to Erasmus to ask his view on some of the intellectual currents then circulating in Germany. “My friend,” he wrote, not mentioning Luther by name, “writes to me that in interpreting St. Paul you understand justification by works . . . ; and secondly that you would not have the Apostle in his epistle to the Romans to be speaking at all about original sin. He thinks therefore that you should read Augustine.”

6

Erasmus did not engage. At this time he was embroiled with controversies closer to home: the long and complex arm wrestling with the French theologian (and rival biblical scholar) Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, and his mounting irritation with the young English scholar Edward Lee, a former protégé whose criticism of his New Testament would become a dangerous obsession for Erasmus over the next few years. When Erasmus received a copy of the ninety-five theses in March 1518 he was interested enough to send the copy on

to his friend Thomas More in London, but his covering letter does not name Luther as the author.

7