Bloody Times (17 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

It was not until the skirmish between two regiments of the same army was over that Colonel Pritchard became aware that he had captured the president of the Confederate States of America.

The men traveling with the president had used good judgment on the morning of May 10. No matter how much they desired to open fire on the Union cavalry, they knew they would lose the fight. They might kill several of the enemy, but the Union soldiers, outnumbering them by more than ten to one, might kill them all and then shoot the president. A gunfight at dawn, when visibility was low, might also lead to the deaths of Mrs. Davis and the children. Surrender, however hateful, was the honorable choice.

Truth vs. Myth. Left: The Raglan coat Jefferson Davis actually wore the morning of his capture. Right: The shawl and spurs Davis wore the morning of May 10, 1865.

And so, thirty-eight days after he left Richmond, after a journey through four states by railroad, ferryboat, horse, and wagon, Jefferson Davis was a prisoner. Several of his supporters thought he could have evaded the manhunt and made it all the way to Mexico, Texas, Cuba, or Europe, if only he had placed his own safety ahead of his own wish to continue to fight for the cause and preserve the Confederacy.

No one is sure why Jefferson Davis did not leave the camp that night. Perhaps he was tired. Perhaps he hoped a few more hours of stolen rest would not matter. Perhaps he thought it was too late to escape to Texas. Perhaps he believed that, once he left this camp, he would never see his wife and children again. Perhaps part of him did not want to flee, run away to another country, and vanish from history. We will never know.

Davis failed in his mission. He did not rally the Confederate army or the Southern people to continue the war. He did not escape to Texas to create a new Confederacy across the Mississippi River. But he had done his best. Robert E. Lee once said: “No man could have done better.”

The war, and the manhunt for Jefferson Davis, were over. But he was alive. May 10, 1865, was the end for Jefferson Davis’s country and his presidency. Now Davis would begin a new, twelve-day journey to prison.

That day in the Union capital, people did not rush into the streets to celebrate Davis’s capture. No one knew about it. Georgia was too far away for the news to travel to Washington on the same day. Instead, the newspapers were still filled with headlines and stories about the Lincoln assassination. May 10 was the opening day of the trial for the seven men and one woman accused of being accomplices in John Wilkes Booth’s plot to murder Abraham Lincoln and Secretary Seward. Many people believed that if Davis were captured before the trial ended, he would be rushed to Washington and charged as the ninth conspirator in Lincoln’s murder.

On the morning of their capture on May 10, Davis, his family, and his aides remained defiant. They were not meek prisoners. They objected to the soldiers plundering their belongings, were offended at the disrespectful way the soldiers addressed the president, and scorned their captors as inferiors. To the Southern mind, these rude, ungentlemanly, thieving Yankee troops represented all that was wrong with the North.

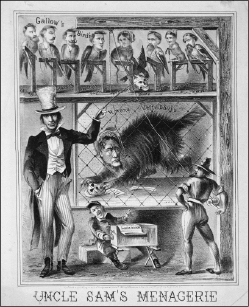

This fanciful print depicts Davis as a caged hyena wearing a lady’s bonnet. The Lincoln assassination conspirators perch above him on gallows, foreshadowing their execution.

Their Southern pride infuriated their captors. The cavalrymen would find a way to settle the score, not with violence but by attacking Jefferson Davis’s most precious possession—his reputation. This was the beginning of the myth that Jefferson Davis was captured in women’s clothing—a myth that is repeated to this day.

“The foolish and wicked charge was made that he was captured in woman’s clothes,” John Reagan wrote indignantly. “He was also pictured as having bags of gold on him when captured. . . . I saw him a few minutes after his surrender, wearing his accustomed suit of Confederate gray, with his boots and hat on . . . and he had no money.”

Davis and his fellow prisoners were taken to Macon, Georgia. From there, on May 14, Davis was taken by train to Atlanta, and then he traveled to Augusta, from where he departed for Savannah.

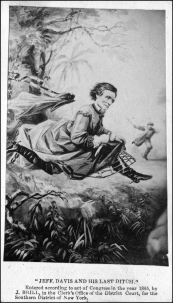

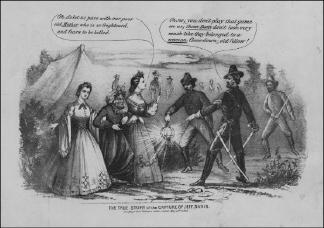

Another popular image that lampooned Davis for allegedly attempting to escape capture dressed as a woman.

On Sunday, May 14, a month after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and ten days after his burial in Springfield, the citizens of Washington read their morning papers and learned stupendous news. Jefferson Davis had been taken. “Thank God we have got the arch traitor at last,” Benjamin Brown French wrote in his diary. “I hope he will not be suffered to escape or commit suicide. Hanging will be too good for him.”

While some hoped to see Jefferson Davis die, others hoped to make a profit out of his capture—particularly the circus owner P. T. Barnum. Barnum owned the American Museum in New York City, full of treasures and curiosities. As soon as he heard the story that Jefferson Davis had been captured in a dress, he wanted it as an exhibit. He wrote to Stanton, offering to make a donation to either the care of wounded soldiers or the care of freed slaves if he could have that dress.

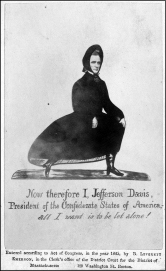

Stanton said no. He planned to keep the gown for himself. But once the clothes worn by Davis during his capture arrived in Washington, Stanton saw that the story was a huge exaggeration. The “dress” was a loose-fitting, waterproof “raglan,” or overcoat. The “bonnet” was a rectangular shawl, a type of wrap President Lincoln had worn on chilly evenings. But the story continued to be told, and drawings, cartoons, and prints all over the country showed Davis in a hoopskirt and a bonnet.

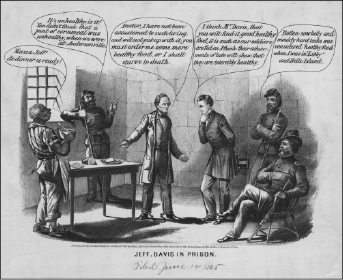

Printmakers continued to ridicule Davis after his capture.

On May 16 Davis arrived in Savannah, Georgia, where he was put aboard a vessel bound for Fortress Monroe, Virginia. Meanwhile, Edwin Stanton was trying to decide what should be done with some prisoners he did not want—Varina Davis and the women who had been arrested with her. He discussed the question with Gideon Welles and General Grant. Stanton exclaimed that the women must be “sent off” because “we did not want them.” “They must go South,” he declared. Welles could not resist toying with him. “The South is very indefinite, and you permit them to select the place. Mrs. Davis may designate Norfolk, or Richmond.” Or anywhere.

Stanton could not stand the idea of the former First Lady of the Confederacy showing up wherever she wanted. “Stanton was annoyed,” Welles saw, and “I think, altered the telegram.” Stanton suspected that if Varina returned to Washington, she could be a dangerous political opponent.

By Monday, May 22, Jefferson Davis was imprisoned in Fortress Monroe, Virginia. He did not know whether he would ever see his wife and children again or even how long he would live. When he parted with Varina, he told her not to cry. It would, he said, only make the Yankees gloat.

His captors refused to address him as “Mr. President.” They called him “Jeffy,” “the rebel chieftain,” or “the state prisoner.” He was always watched, and often not allowed to sleep. Through insult, isolation, and silence, they tried to humiliate him and break his spirit. He was, in the words of some newspapers, the arch criminal of the age, a man “buried alive” who must never be set free. Many people hoped that he would never emerge from his dungeon alive.

Within days of his capture, popular prints ridiculed the Confederate president.

Shortly after he was shut inside his prison, men entered Davis’s cell and told him they had orders to shackle him. Davis saw the blacksmith with his tools and chains. He told them all that he refused to allow such a humiliation, pointed to the officer in charge, and said he would have to kill him first. Davis dared his jailers to shoot him.

Soldiers lunged forward to grab him, but Davis knocked one man aside and kicked another away with his boot. Then several ganged up on him, seized him, and held him down while the smith locked the chains in place.