Bloody Times (16 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

On May 7 Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Pritchard, commanding the Fourth Michigan Cavalry regiment, left Macon, Georgia, in pursuit of Jefferson Davis. His orders were to capture or kill him.

On May 8 Davis separated from his family again. At dawn he rode on. By nightfall he had made little progress through heavy rains, and Varina’s train caught up with him. Before dawn on May 9 they were together once more.

Lieutenant Colonel Pritchard and his men arrived at Abbeville, Georgia, at 3:00

P.M.

on May 9. There he encountered the commander of the First

Wisconsin Cavalry, who told Pritchard that a wagon train had crossed the Ocmulgee River the night before, a mile and a half north of Abbeville.

The Wisconsin men went off down the main road while Pritchard’s soldiers planned to follow the river. Pritchard left Abbeville at 4:00

P.M.

, headed toward Irwinville.

Toward the end of the day on May 9, Davis decided to make camp for the night with Varina’s wagon train near Irwinville. They pulled off the road, and pine trees helped conceal their position. The tents and wagons were scattered over an area of about one hundred yards. Any Yankee who rode into one part of the camp during the night would not be able to see to the other side of it. Davis, unless captured at once, could escape into the woods under the cover of darkness. The layout was perfect, except for one flaw. Despite two dangers—thieves looking for plunder and the Union cavalry hunting for Davis—they posted no guards to keep watch.

When Jefferson Davis entered his wife’s tent late on the night of May 9, 1865, he was lucky to still be a free man. Davis’s advisers knew that it was too dangerous for the president to continue traveling with his wife’s slow-moving wagon train. Unless Davis left his family and moved fast on horseback, along with just three or four men, he had little chance of escape.

Davis said that on the night of May 9 he would eat dinner, stay up late, and leave on horseback under cover of darkness. He was dressed for the road: dark felt, wide-brimmed hat; wool frock coat of Confederate gray; gray trousers; high, black leather riding boots and spurs. His horse was tied near Varina’s tent, already saddled, with his saddle holsters loaded with Davis’s pistols, ready to ride.

Several of the men, including John Reagan, stayed up late talking, waiting for Davis to give the order to depart. It never came. The delay puzzled one of the men picked to accompany the president. “Time wore on, the afternoon was spent, night set in, and we were still in camp,” he wrote later. “Why the order ‘to horse’ was not given by the President I do not know.”

Pritchard’s men arrived in Irwinville at 1:00

A.M.

on May 10, but found no traces of Davis or his followers. Pritchard rode ahead with a few men and, posing as Confederate cavalrymen, they questioned some villagers. The locals told Pritchard that at sunset a party with wagons had camped a mile, or a mile and a half, from town out on the Abbeville road.

Pritchard positioned his men about half a mile from the mysterious encampment. He sent twenty-five men, guided by a local black man and under the command of Lieutenant Alfred Purington, to circle around the camp and cut off any chance of escape from the rear. He waited for daylight. He didn’t want any of the Confederates to escape into the woods under cover of darkness.

For the next hour and a half, they waited in the dark.

At 3:30

A.M.

, at the first hint of dawn, Pritchard ordered his men into their saddles and to ride forward. After a quick dash, they succeeded in capturing the camp and everyone in it. Pritchard’s men had not fired a shot. “The surprise was so complete,” Pritchard wrote later, “that few of the enemy were enabled to make the slightest defense, or even arouse from their slumbers in time to grasp their weapons, which were lying at their sides, before they were wholly in our power.”

But before Pritchard’s men could gain full control, and before the colonel was even sure that he had captured Jefferson Davis’s camp, gunfire broke out. It came from behind the camp, where Pritchard had sent Lieutenant Purington and his twenty-five men. It was a rebel counterattack, Pritchard assumed. He spurred his horse past the tents and wagons and rode to the sound of the fighting.

Lieutenant Purington and the men under his command were in position behind Davis’s camp, waiting for Pritchard’s signal. As Purington faced Davis’s camp, he heard mounted men approaching him from his rear. They called out that they were “friends.” But they refused to identify themselves and would not ride forward when Purington ordered them to. One of them shouted, “By God, you are the men we are looking for,” and began to ride away. Purington ordered his men to open fire.

In the dark the two groups of armed men could not see that they wore the same uniform, Union blue cavalry shell jackets decorated with bright yellow piping. The Fourth Michigan Cavalry was fighting the First Wisconsin.

The gunfire woke the people in Jefferson Davis’s camp, and one man sounded the alarm. “I was awakened by the coachman, Jim Jones,” Burton Harrison remembered, “running to me about day-break with the announcement that the enemy was at hand!” Harrison drew his pistol and faced several men from the Fourth Michigan charging up the road from the south. He raised his weapon and took aim.

“As soon as one of them came within range,” Harrison said, “I covered him with my revolver and was about to fire, but lowered the weapon when I perceived the attacking column was so strong as to make resistance useless, and reflected that, by killing the man, I should certainly not be helping ourselves. . . . We were taken by surprise, and not one of us exchanged a shot with the enemy.”

John Reagan, the postmaster general, was there as well. “The major of the regiment reached the place where I and the members of the President’s staff were camped,” he said later. “When he approached me I was watching a struggle between two federal soldiers and Governor Lubbock. They were trying to get his horse and saddle bags away from him and he was holding on to them and refusing to give them up; they threatened to shoot him if he did not, and he replied . . . that they might shoot and be damned, but that they should not rob him while he was alive and looking on.”

Jefferson Davis, still inside Varina’s tent, had received his coachman’s warning. He now heard the gunfire and the horses in the camp. He assumed that the riders were Confederate deserters, thieves planning to rob Mrs. Davis’s wagon train. “Those men have attacked us at last,” he warned his wife. “I will go out and see if I cannot stop the firing; surely I still have some authority with the Confederates.” Upon going to the tent door, however, he saw the blue coats of the Union soldiers and turned to Varina. “The Federal cavalry are upon us,” he told her.

Davis had not undressed during the night. He needed no time to get ready. His pistols and saddled horse were within sight of the tent. If he could get to that horse, he could leap into the saddle and gallop for the woods. He was still a superb rider and must have felt that he could outride any Yankee cavalryman half his age. Seconds, not minutes, counted now, and if he hoped to escape he had to act at once.

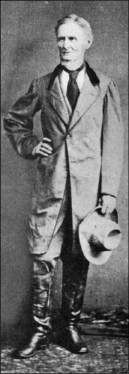

Before he left, Varina asked him to wear an overcoat, also known as a “waterproof.” It was cool and drizzling, and if he could escape the camp, he faced several hours of hard riding. The extra layer of warmth might help, and the coat might also conceal his identity. “Knowing he would be recognized,” Varina explained, “I plead with him to let me throw over him a large waterproof which had often served him in sickness during the summer as a dressing gown, and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was round my own shoulders, seeing that he could not find his hat.” These two garments—the coat and shawl—would help create a myth that Davis had attempted to evade capture by wearing women’s clothing.

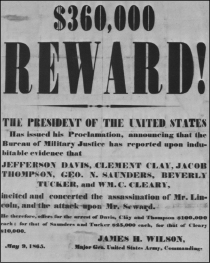

Popular images lampooned Davis for allegedly attempting to escape capture dressed as a woman.

Jefferson Davis described what happened next. “I had gone perhaps between fifteen or twenty yards when a trooper galloped up and ordered me to halt and surrender, to which I gave a defiant answer, and, dropping the shawl and the raglan from my shoulders, advanced toward him.” The soldier leveled his weapon at Davis, but the Confederate president did not hesitate. “But I expected, if he fired, he would miss me, and my intention was in that event to put my hand under his foot, tumble him off on the other side, spring into the saddle, and attempt to escape. My wife, who had been watching me, when she saw the soldier aim his

carbine

at me, ran forward and threw her arms around me. . . . Recognizing that the opportunity had been lost, I turned back, and, the morning being damp and chilly, passed on to a fire beyond the tent. . . .”

The manhunt was over. Jefferson Davis and everyone with him had been captured. But the gunfire was still going on. One of Davis’s men warned Pritchard that if shots were being fired, it was not the Confederates being killed. “Captain, your men are fighting each other over yonder,” he said.

Pritchard was sure that Davis’s camp must be protected by more soldiers. But the other man insisted that he was wrong. “You have our whole camp; I know your men are fighting each other,” he said.

Soon Pritchard and his officers discovered it was true. There were no Confederate soldiers behind the camp, only two Union regiments—the Fourth Michigan and the First Wisconsin. All were attempting to earn the glory of capturing Jefferson Davis and the gold he was supposed to have with him. Every Union soldier had heard the rumors—the “rebel chief” was fleeing with millions of dollars in gold coins. Yes, Confederate treasure was on the move in April and May 1865, but what the manhunters did not know was that Jefferson Davis was not the one transporting it.

A second reward poster for Davis and other Confederate leaders. Neither Davis nor his pursuers learned of the reward until after he was captured.

The gun battle caused hard feelings between the two regiments. They blamed each other and fought over the reward money promised to whoever captured Davis. The Fourth Michigan wanted to claim all the money and did not want to share it with the First Wisconsin. The Wisconsin men complained that if the Fourth had not fired upon them, then they would have been the ones who would have captured Davis.

On the morning of his capture, Jefferson Davis wore a suit of Confederate gray and not one of Varina’s hoop skirts.

Jefferson Davis, who sacrificed all he had for the Confederacy and who was captured penniless, without a single dollar to his name, must have appreciated the irony. He never commented about it, but it surely amused him to see Yankees killing each other and squabbling over money in their zeal to claim him as their prize.