Bloody Times (14 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

The train pulled into Columbus at 7:30

A.M.

, Saturday, April 29. Again there was a procession and a viewing in yet another building draped with black and overflowing with flowers. The hearse drove off and, as usual, left behind on the train a coffin that had accompanied Lincoln from Washington. In newspaper stories of the funeral train, little mention was made of Willie Lincoln. His small coffin was never unloaded from the train. But in Columbus Willie Lincoln was not forgotten. General Townsend recalled: “While at Columbus I received a note from a lady,” he wrote, “accompanying a little cross made of wild violets. The note said that the writer’s little girls had gone to the woods in the early morning and gathered the flowers with which [they] had wrought the cross. They desired it might be laid on little Willie’s coffin, ‘they felt so sorry for him.’”

On April 29 Jefferson Davis crossed the Saluda River in South Carolina. Federal soldiers were having a difficult time picking up his trail. One Yankee cavalryman complained, “The white people seemed to be doing all they could to throw us off Davis’ trail and impart false information to their slaves, knowing the latter would lose no time in bringing it to us.”

The Union general in charge of the manhunt for Davis did not know exactly where to look—but it didn’t really matter. He expected Davis to head for Georgia, or perhaps make it all the way to Florida, and so he planned to blanket the entire region with troops. If Davis went south, someone would find him.

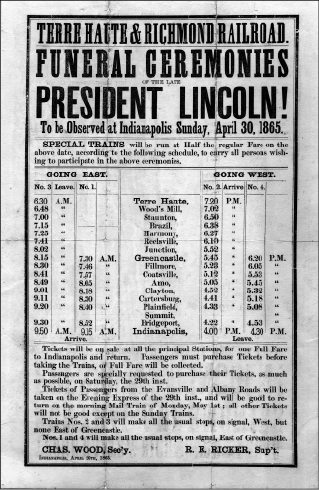

Railroads ran special trains to the cities where Lincoln’s body lay in state.

At 8:00

P.M.

tolling bells signaled the train’s departure from Columbus. It steamed west and crossed into Indiana in the middle of the night. At 7:00

A.M.

on Sunday, April 30, the train arrived in Indianapolis. In the rain, a hearse fourteen feet high and fourteen feet long drew the president to the dome of the state capitol, where he would lie in state for more than fifteen hours and be seen by more than a hundred thousand people.

At midnight the train set off again for Chicago.

Around the same time, Varina wrote a letter to her husband. “I have given up hope of seeing you but it is not for long,” she told him. She hoped to “take a ship or what else I can . . . still think we will make out somehow. May the Lord have you in his holy keeping I constantly, and earnestly pray. . . . The children have been more than good, and talk much of you. . . .”

The funeral train reached Chicago on May 1 at 11:00

A.M.

Guns fired to announce its arrival. Tens of thousands of people had been waiting in the streets for hours. One spectator wrote that “every window was filled with faces, and every door-step . . . filled with human beings.” A newspaper even suggested that the rough waters of Lake Michigan “suddenly calmed from their angry roar into solemn silence” as if they, too, mourned for Lincoln.

At the train station a huge funeral arch had been set up. Lincoln’s coffin was laid near it, and thirty-six high school girls, each dressed in white and wearing a black sash, placed a flower on the coffin. Then the honor guard placed the coffin in the hearse, and the procession to the courthouse began. Ten thousand children marched in line behind groups of soldiers and city officials. More than 120,000 people took part in or witnessed the procession. One of them, Daniel Brooks, had, as a sixteen-year-old boy, taken part in George Washington’s funeral procession in 1799.

The Chicago funeral arch.

The hearse stopped at the courthouse, and the coffin was carried inside and laid upon a platform. Over the platform was a canopy of heavy cloth into which had been cut thirty-six stars. The light shone through the stars and fell on the coffin below.

The public viewing began at 5:00

P.M.

, and by midnight more than forty thousand people had seen Lincoln’s corpse.

Jefferson Davis had spent a quiet night in Cokesbury, South Carolina. He left there on May 2 before daylight, and at about 10:00 that morning he rode into Abbeville. The townspeople were happy to see him. Captain William Parker, the officer safeguarding the Confederate treasure wagon train, had arrived before Davis. Parker turned the gold over to John Reagan and allowed the young cadets who had been guarding the treasure to leave for home.

Then Parker called on Davis. “I never saw the President appear to better advantage than during these last hours of the Confederacy,” remembered Parker. “He showed no signs of despondency. His air was resolute; and he looked, as he is, a born leader of men.”

When Davis heard that Parker had dismissed his band of cadets, he said, “Captain, I am very sorry to hear that,” and repeated the words several times. Still hopeful that he could rally the troops, Davis was unhappy about the loss of even a single soldier from the Confederate forces. Parker explained that the secretary of the navy had given the order. “I have no fault to find with you,” said Davis, “but I am very sorry Mr. Mallory gave you the order.”

Davis suggested that they remain in Abbeville for four days, but Parker warned him that if he stayed that long he would be captured. Davis replied that he would never desert the Southern people. He rose from his chair and began pacing the floor, repeating several times that he would “never abandon his people.”

Parker spoke frankly: “Mr. President, if you remain here you will be captured. . . . You will be captured, and you know how we will all feel that.” Parker told his president, “It is your duty to the Southern people not to allow yourself to be made a prisoner.” He advised Davis on how to escape: “Leave now with a few followers and cross the Mississippi.”

Parker was not the only one giving that advice to Davis. On the same day Varina wrote to her husband, worried for his safety. “Do not try to meet me,” she told him. “I dread the yankees getting news of you so much, you are the countrys only hope. . . . Why not cut loose from your escort? Go swiftly and alone with the exception of two or three. . . . May God keep you, my old and only love, As ever Devotedly, your own Winnie.”

After Davis talked with Parker, he received more bad news. He met with several cavalry officers and asked them about the “condition and spirit” of their men. Were they able and willing to go on fighting?

The answer was discouraging. The officers told him frankly that “they could not depend upon their men for fighting, that they regarded the struggle as over.” Davis was again urged by his advisers to make his way quickly to Florida or across the Mississippi, but he still refused. “The idea of personal safety, when the country’s condition was before his eyes, was an unpleasant one to him,” remembered Stephen Mallory. He was not yet willing to flee for his own life.

Mallory decided that there was nothing more he could do to help Davis. At Abbeville he gave up his job as secretary of the navy. His family needed him, he said, and he did not want to flee the country and abandon them. But he agreed to remain with Davis’s party for a few more days.

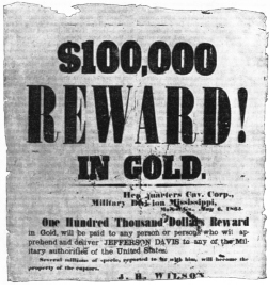

On May 2 President Andrew Johnson offered a reward of one hundred thousand dollars for Jefferson Davis’s capture. The announcement of it accused Davis of being involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

The first reward poster for Jefferson Davis.

By noon on May 2, the line of people in Chicago waiting to view Lincoln’s body stretched nearly a mile. They came all day, and when the doors to the courthouse were shut at 8:00

P.M.

, the thousands of people still waiting in line had to be turned away. This was a city that felt a special relationship with Abraham Lincoln. He had worked here as a lawyer in the courts; his most famous campaign debates had been held here; and five years ago here he had accepted the nomination to become president. And now, the

Chicago Tribune

newspaper wrote, “he comes back to us, his work finished.”

The funeral train left Chicago at 9:30

P.M.

The excitement aboard the train increased. This was the last night. In the morning the funeral train would complete its journey, and Lincoln’s body would return to Springfield. As the train passed through a town called Lockport, a sign was seen on a house. It read, “Come home.”

During the night of May 2 and through the early morning hours of May 3, the residents of Springfield were restless. They had been getting ready for Lincoln’s homecoming since they heard news of his death. Now they had finished hanging the decorations and painting the signs. Crepe and bunting blackened the town. Lincoln’s own two-story house was a decorated masterpiece of mourning. Over the front door of his law office hung a sign that read, “He Lives in the Hearts of His People.”

They had waited eighteen days since Lincoln’s death and thirteen days since the train had left Washington. Beginning tomorrow, over the next two days of May 3 and 4, Springfield would show the nation that no town loved Abraham Lincoln more.

That night, more of Jefferson Davis’s advisers begged him to flee with a small escort of three officers and make a run for the coast of Florida. Davis, once again, refused. But he did agree to leave Abbeville that night, instead of staying several days.

Davis wrote to Burton Harrison about his plans. The letter was not a happy one, and Davis even expressed his low opinion of the Confederate soldiers and his worry about the Union soldiers hunting for him. “I think all their efforts are directed for my capture and that my family is safest when furthest from me—I have the bitterest disappointment in regard to the feeling of our troops, and would not have any one I loved dependent upon their resistance against an equal force,” he wrote.

At 11:00

P.M.

Davis left Abbeville. The wagons carrying the Con-federate treasury followed, watched over by Secretary of State Benjamin.

* * *

On the morning of May 3, Lincoln arrived in Springfield. His journey was complete.

Edward Townsend sent his usual matter-of-fact telegram to Stanton: “The funeral train arrived here without accident at 8.40 this morning. The burial is appointed at 12 p.m. to-morrow, Thursday.”

Townsend had done it. Under his command, the funeral train had taken the corpse of Abraham Lincoln 1,645 miles from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, and it had arrived on schedule. During its thirteen-day journey, the train never broke down, suffered an accident, or left one city a minute late.

At every stop along the way, the soldiers of the honor guard had performed perfectly. Not once did they falter in their handling of the heavy coffin. Whenever they carried the president, whether on level ground, up and down steep winding staircases, or onto a ferryboat, whether in daylight or darkness, in sunshine or a driving rain, the veteran Union army soldiers never made a misstep. Now, in Springfield, they would carry the president of the United States upon their shoulders for the last time.