Blood Brotherhoods (79 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Kidnapping proved less divisive in the ’ndrangheta than it did in Cosa Nostra. But the new criminal industry did attract media and police attention to Calabria, and therefore controversy within the local underworld. It seems that the

tarantella

dancer and triumvirate member, don ’Ntoni Macrì, made his misgivings about having hostages on his territory known to the other bosses not long after the Getty kidnapping. These misgivings further increased the rivalries between the ’ndrangheta factions that were trying to get their hands on the Colombo package.

Gangsters from the South and Sicily were by no means the only people to profit from the wave of abductions across the country in the 1970s and

1980s. For example, bandits from the island of Sardinia, some of the most active of them operating off-base in Tuscany, had their own tradition of hostage-taking and were particularly active in the 1970s. Many ordinary delinquents latched on to the idea that taking a hostage or two was a short cut to riches. Kidnapping became a criminal craze that was profoundly damaging to Italy’s weakened social fabric.

Luigi Ballinari, a drunken, small-time cigarette smuggler of Swiss nationality, recalled the buzz in prison in 1974: ‘Our conversations always came back to the crime of the moment, which was now a fashion in Italy: extorting money by kidnapping. It was everyone’s dream! We fantasised, we organised, we analysed the mistakes that other kidnappers had made.’

Soon after being released, Ballinari became involved in one of the most atrocious kidnappings of the era. Cristina Mazzotti, nineteen-year-old daughter of an entrepreneur from near Como, on the Swiss border, was taken on 26 June 1975. Her captors stripped, blindfolded and manacled her, blocked her ears, and lowered her into a tiny space below a garage floor. There she was made to consume sleeping pills dissolved in fruit juice for more than two weeks during negotiations with her parents. The plan—one common to many improvised kidnapping groups in the North and centre of Italy—was to sell the hostage on to the real experts: the ’ndrangheta. But in this case, before Cristina could be bartered and sent to a new prison on Aspromonte, her body slowly shut down under the cumulative effect of the drugs; she was loaded into a car boot and buried in a rubbish dump. Her parents, unaware that she was already dead, paid a ransom of 1.05 billion lire ($6.9 million in 2011 values).

Ballinari was later caught trying to launder some of the profits from Cristina’s abduction. By the time he buckled under interrogation, and told the whole story, Cristina’s body was so decomposed that it proved hard to tell whether she had actually been dead when she was interred.

The horrors of the kidnapping industry were legion. The captives on Aspromonte were particularly badly treated. Shackled and fed on scraps, they were not allowed to wash and their clothes were never changed. In intercepted phone conversations, their ’ndrangheta captors were heard referring in code to the prisoners as ‘pigs’. The longest kidnapping was that of teenage student Carlo Celadon from near Vicenza, who was snatched in his own home in 1988. Carlo was kept for a mind-boggling 828 days in a rat-infested grotto scattered with his own excrement. With three chains round his neck, he was subject to constant threats—and to beatings if he dared cry or pray. When he was released, his father commented that he looked like the inmate of a Nazi concentration camp. Carlo’s comment on his ordeal was harrowing: ‘I asked, I begged my jailers to cut my ear off. I was totally destroyed, I had lost all hope.’

In Italy as a whole, between 1969 and 1988, seventy-one people vanished and were never seen alive again; it is thought that in roughly half those cases, a ransom was paid. In 1981 Giovanni Palombini, an eighty-year-old coffee entrepreneur, was kidnapped by a Roman gang who probably intended to pass him on to the ’ndrangheta. He managed to escape, but was so disorientated that when he knocked on the door of a villa to ask for help, it turned out to be his kidnappers’ hideout. He was given a glass of champagne, and then executed. His body was thrown in a freezer so that it could be pulled out for the photographs his family wanted to see to be certain that he was still alive.

Children were not spared: there were twenty-two abductions of children, some no more than babes in arms. Marco Fiora was only seven years old when

’ndranghetisti

grabbed him in Turin in March 1987. His ordeal lasted a year and a half, during which time he was kept chained up like a dog in an Aspromonte hideaway. His captors did their best to brainwash him, telling him that his parents did not want to pay the ransom because they did not love him. It seems that the long delay was due to the fact that the ’ndrangheta’s spies had greatly overestimated how rich Marco’s father was, and refused to believe his claims that he could not afford the ransom. Marco was skeletal when he was released near Ciminà, and his legs were so atrophied that he could barely walk. He knocked on a few doors, but the inhabitants refused to open. So he just sat down by the roadside until a patrol of

Carabinieri

happened upon him. His first words to his mother were, ‘You aren’t my mummy. Go away. I don’t want to see you.’

Some children fared even worse. A little girl of eleven from the shores of Lake Garda, Marzia Savio, was taken in January 1982. Her captor turned out not to be a gangster, but just the local sausage butcher who thought he had found a neat way to make some quick money. He strangled Marzia, probably while he was trying to restrain her, and then cut her into pieces that he scattered from a flyover.

Kidnapping became so common that it acquired its own rituals in the news bulletins and crime pages. The victims’ families giving anguished press conferences. Or, conversely, desperately attempting to shun the limelight and avoid provoking whoever was holding their father, their son, their daughter. There was the long, anguished wait for the kidnappers to make known the ransom demands. There were hoax calls from ghoulish pranksters.

Kidnapping is a crime that creates and spreads mistrust. Many families rightly suspected that friends and employees had leaked information to the criminals. Finding reliable lines of communication and intermediaries was often agonising. The family of Carlo Celadon, the young man who was held for a record 828 days, alleged that the lawyer they delegated to transport the

ransom had pocketed a proportion of it. (He was convicted of the crime but later benefited from an amnesty before his appeal.) The ’ndrangheta sometimes seemed to know more about how much their hostages earned than did the tax man. For that reason, the media tended to cast suspicion over the finances of even the most honest victims. Hostages’ families were often warned against going to the police. And the police were often frustrated by families’ silence: some had the indignity of being arrested for withholding information after seeing their loved ones freed.

The poison of mistrust leaked into the public domain. Each high-profile abduction triggered a vitriolic and, for a long time, entirely inconclusive debate between journalists, politicians and law-enforcement officials. There were those who favoured the hard line on kidnapping: refusing to pay ransoms, freezing victims’ assets, and the like. Ranged against them were those who thought the ‘soft line’ (i.e., negotiation) was the only humane and practical option. Some of the more pugnacious entrepreneurs of the North underwent weapons training. The situation became so bad that, in 1978, one magistrate discovered that some wealthy families were taking out special insurance policies so that they would have enough money for a ransom when the masked bandits paid their seemingly inevitable visit. Wealthy citizens—the class of person who, in other Western democracies, would almost automatically be loyal to the powers that be—were angry, alienated and afraid.

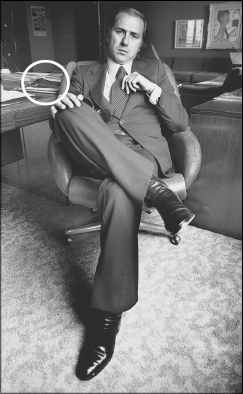

There is a photo that makes for an intriguing memento of that terrible era of fear and mistrust. It shows a self-confident young Milanese construction entrepreneur leaning back in a chair. His serious expression shows no hint of the permanent matinée idol smile that would later become his worldwide trademark. He has just removed a pair of aviator sunglasses, and the flared trousers of his suit reveal the trendy ankle boots on his feet. But it is not his dress and accessories that really make the photo symptomatic of the 1970s. Rather it is the holstered pistol that sits on his desk. The entrepreneur’s name is Silvio Berlusconi, and around the time the photo was taken, he had the well-grounded dread of kidnapping that was common to many wealthy Italians. However Berlusconi’s business factotum, a Sicilian banker called Marcello Dell’Utri, found a more effective way to calm these fears than a pistol in a desk drawer. From 1974 to 1976, Vittorio Mangano, a

mafioso

from Palermo, took a not terribly clearly defined job (groom? major domo? factor?) at Berlusconi’s newly acquired villa at Arcore. The Italian courts have recently ascertained that, in reality, Mangano was a guarantee of Cosa Nostra’s protection against kidnapping. Moreover, he was also there with the intention of making friends. Or, in the language of a judge’s ruling, Mangano was part of a ‘complex strategy destined to make an approach

to the entrepreneur Berlusconi and link him more closely to the criminal organisation’.

In the 1970s, many wealthy people armed themselves as a defence against mafia kidnappers. Here a young Berlusconi is pictured with a gun on his desk (circled).

Marcello Dell’Utri has been convicted of a long-standing collaboration with Cosa Nostra that included recommending Vittorio Mangano’s services to Berlusconi. He still denies the charges, which he says are the result of a judicial plot against him. The case has gone to the Supreme Court.

Vittorio Mangano was later sentenced to life for two murders, and died of cancer in 2000. He died like a good

mafioso

should, without shedding any light on the case.

Silvio Berlusconi’s own public utterances on the affair have been disturbing, to say the least. For example, he gave his view of the

mafioso

in a radio interview in 2008:

[Mangano] was a person who behaved extremely well with us. Later he had some misadventures in his life that placed him in the hands of a criminal organisation. But heroically . . . despite being so ill, he never invented any lies against me. They let him go home the day before he died. He was dying in prison. So Dell’Utri was right to say that Mangano’s behaviour was heroic.

Quite whether the kidnapping season was the beginning of a direct long-term relationship between Berlusconi and the Sicilian mafia is not clear. It should be stressed that Berlusconi has never been charged with anything in relation to the Mangano affair.

Every kidnapping was a clamorous demonstration of the governing institutions’ inability to protect life and property. Italy was getting visibly weaker at the very same time that the mafias were getting stronger, richer, more

interlinked, and closer to descending into war. The state seemed to have lost its claim to a ‘monopoly of legitimate violence’, as the jargon of sociology would have it. In the 1970s, while the wave of kidnappings spiralled out of control, a new wave of economic and political troubles brought further discredit on the state.