Blood Brotherhoods (80 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Italy, like the rest of the developed world, had to face a grave economic crisis following a dramatic hike in crude oil prices in 1973. There ensued a decade of stuttering growth, high unemployment, raging inflation, steepling interest rates and massive public debt. Violent social conflict was on the rise. The trades unions that had been so pugnacious since the ‘hot autumn’ of 1969 now went on the defensive. As a result, some members of Italy’s revolutionary groups lost patience with peaceful forms of militancy; they opted instead to form clandestine armed cells. These terrorists, as ruthless as they were deluded, thought of themselves as a revolutionary vanguard who could hasten the advent of a Communist society by maiming or assassinating strategically chosen targets. Italy had entered its so-called ‘Years of Lead’ (i.e., years of bullets).

The Red Brigades (or BR) would turn out to be the most dangerous of these groups, and many of their earliest actions were kidnappings. The victims—usually factory managers—would typically be subjected to a ‘proletarian trial’, and then chained to the factory gates with a placard daubed with a revolutionary slogan round their necks. In the spring of 1974, under the new slogan of ‘an attack on the heart of the state’, the BR hit the headlines by kidnapping a judge from Genoa. The BR’s demands were not met, but the judge was released unharmed.

After a wave of arrests brought a lull in their activities in the middle of the decade, the Red Brigades returned with more terroristic resolve than ever. On 16 March 1978, they brought the country to a standstill by kidnapping the former Prime Minister and leader of the Christian Democrat Party, Aldo Moro. Moro’s driver and his entire police escort were murdered in the assault. On 9 May Moro was himself shot dead, and his body was abandoned in a car in the centre of Rome. The BR and other groups continued their murder campaign into the following decade. Many young people, in particular, could not find it within themselves to identify with the authorities in their fight against terrorism: ‘Neither with the state, nor with the Red Brigades’ was one political slogan of the day. This was the state that would soon have to face up to unprecedented mafia violence. Calabria was to be the first place where war broke out.

T

HE

M

OST

H

OLY

M

OTHER AND THE

F

IRST

’N

DRANGHETA

W

AR

W

HEN EVIDENCE OF ORGANISED CRIME

’

S VAST NEW WEALTH EMERGED IN THE

1960

S

and 1970s, many observers claimed that, in both Sicily and Calabria, the traditional mafia was being replaced by a new breed. The mafia was now no longer rural, but urban; it was a ‘motorway mafia’, rather than a donkey-track mafia; these were gangsters in ‘shiny shoes’ rather than the muddy-booted peasants of yesteryear. The new model

mafioso

, it was claimed, was a young, aggressive businessman. In particular, he had no time for the quaint, formalistic concerns of the Honoured Societies, or for the antediluvian cult of honour. Backward Calabria was where the transformation appeared to be most marked. Here, even many who took the mafia threat seriously thought that initiation rituals; Osso, Mastrosso, Carcagnosso; and the meeting at the Sanctuary of the Madonna of Polsi were bound to be consigned to the folklore museum—if they hadn’t been already.

The De Stefano brothers, Giorgio, Paolo and Giovanni, fitted most people’s idea of the emergent gangster-manager. The brothers came from Reggio Calabria, the town that was bigamist don Mico Tripodo’s realm. As we have already seen, Tripodo spent much of his time away in Campania, cementing close friendships with the

camorristi

of the Neapolitan hinterland. But a boss can only remain away from his territory for so long before the ground shifts behind him. In don Mico’s absence the De Stefanos emerged as a power in their own right.

Giorgio, the oldest of the brothers and the most cunning, was referred to by one ’ndrangheta defector as ‘the Comet’—the rising star of Calabrian organised crime. The De Stefanos were the most enthusiastic participants in the Reggio revolt, and the keenest to make friends with Fascist subversives. And they were certainly young: none of them was out of his twenties at the time of the Montalto summit. The triumvirs whose authority the De Stefanos would come to challenge were from an older generation: the

tarantella

-dancing don ’Ntoni Macrì could just about have been their grandfather.

One

’ndranghetista

also remembered the De Stefanos as being educated, at least by the standards of the Calabrian underworld, recalling that: ‘Paolo and Giorgio De Stefano attended university for a few years. Giorgio was signed up to do medicine, and I think Paolo studied law.’ That education was visible. Pictures of Giorgio (‘the Comet’) and Paolo, the two oldest and most powerful De Stefano brothers, show men with large, sensitive faces and black hair parted neatly at the side. Their up-to-date, clean-cut image could hardly be more starkly different from the grim physiognomies of the triumvirs: Mico Tripodo and the others all had mean little eyes, cropped hair and sagging, expressionless faces; each seemed to have been assembled from the same old kit of atavistic hoodlum features.

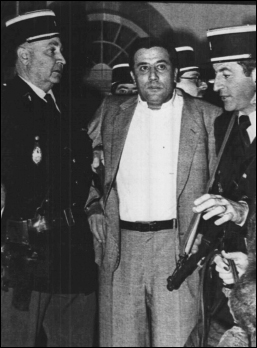

The face of the new ’ndrangheta? Paolo De Stefano in 1982.

As it turned out, these contrasting faces, and the switch from tradition to modernity that they seemed to make visible, proved to be no guide to the winners and losers who would emerge from the unprecedented criminal

wealth and violence of the 1970s. The simplistic ‘modernity versus tradition’ template that was used to make sense of the events of the 1970s was just a bad fit with reality. For one thing, the rise of ambitious young thugs like the De Stefanos from within the ranks of the organisation is not a novelty. For another, even in Calabria, there is nothing new about

mafiosi

with middle-class credentials. Nor are the mafias traditional in the sense of being very old. On the contrary, they are as modern as the Italian state.

It is much nearer the mark to say that the ’ndrangheta, like Cosa Nostra, is

traditionalist

, in the sense that it has manufactured its own internal traditions that are functional to the demands of extortion and trafficking. When the ’ndrangheta grew richer, through the construction industry, tobacco smuggling and kidnapping, it did not simply abandon its traditions and embrace modernity. From their origins, Italy’s mafias have always

mixed

tradition and modernity. Their response to the new era was to

adapt

the mixture. Or indeed, in the case of the ’ndrangheta, to invent brand-new traditions like the one that is the subject of this chapter: the Most Holy Mother. That newly minted tradition is significant for two reasons. First, it provides evidence of just how many friends the mafias, with their new wealth, were making among the Italian elite. Second, the Most Holy Mother became the trigger of the First ’Ndrangheta War. And to understand it, we need to grasp some subtle but important differences between the ’ndrangheta and Cosa Nostra.

The ’ndrangheta and Cosa Nostra are very similar in that they are both Honoured Societies—Freemasonries of crime. Both organisations are careful about choosing whom they admit to the club. No one with family in the police or magistracy is allowed in. No pimps. No women.

Yet there are also some differences in the way the two select their cadres.

’ndranghetisti

tend to come from the same blood families. Cosa Nostra, by contrast, has rules to

prevent

too many brothers being recruited into a single Family, in case they distort the balance of power within it. In some cases, two brothers may even enter

different

Families.

Cosa Nostra tends to monitor aspiring gangsters carefully before they cross the threshold of the organisation, often making a criminal wait until his thirties so that he can prove over the years that he is made of the right stuff. The Calabrian mafia admits many more people. A police report from 1997 estimated that in Sicily there were 5,500

mafiosi

, or one for every 903 inhabitants. By comparison, there were 6,000

’ndranghetisti

in Calabria, or one for every 345 citizens. In the most ’ndrangheta-infested province,

Reggio Calabria, there was one affiliate for every 160 inhabitants. In other words, proportionally speaking, the ’ndrangheta admits two and a half times as many members. The male children of a boss are initiated willy-nilly. Some even go through a ritual at birth. But that does not mean that the Calabrian mafia has watered-down membership criteria. Rather it suggests that it does much of the business of monitoring and selecting members

once they are inside

. A winnowing process continues through each

’ndranghetista

’s entire career. Only the most criminally able of them will rise through the ranks. Young hoods may learn to specialise either in business or in violence.

At this point, it helps to recall the stages of a Calabrian mafioso’s career. As he acquires more prestige, he progresses through a hierarchy of status levels. An

’ndranghetista

starts off as a

giovane d’onore

(‘honoured youth’—someone marked out for admission into the organisation, but who is not yet a member). Through day-by-day service to his superiors—issuing threats and vandalising property as part of extortion demands, collecting protection payments, hiding weapons and stolen goods, ferrying food up to the mountain prisons where hostages are kept—he rises to become a

picciotto

(‘lad’), and then on up the ladder through a long list of other ranks.

As we have seen, ranks are called

doti

(‘gifts’). Being promoted to a higher gift is referred to as receiving a

fiore

(a ‘flower’). The giving of each flower is marked by a ritual. But secrets, rather than gifts, are the true measure of status in the ’ndrangheta. Since it began in the nineteenth century, each ’ndrangheta cell has had a double structure made of sealed compartments: the Minor Society and the Major Society. Younger, less experienced and less trustworthy recruits belong to the Minor Society. Minor Society members are insulated from understanding what goes on in the Major Society to which the more experienced crooks belong. Promotion through the ranks, and from the Minor Society to the Major Society, implies access to more secrets.

As profits rose within the ’ndrangheta in the early 1970s, and tensions increased, so too did the tinkering with these peculiarly complicated protocols. Until the early 1970s, the highest gift that any affiliate of the ’ndrangheta could attain was that of

sgarrista

. Literally,

sgarrista

means something like ‘a man who gives offence, or who breaks the rules’. (The terminology, like so much else about the ’ndrangheta, dates back to the nineteenth-century prison system.)

Around 1972–3, some chief cudgels began to create a new, higher gift for themselves:

santista

(‘saintist’ or ‘holy-ist’). With the new status came membership of a secret elite known as the Mamma Santissima (‘Most Holy Mother’) or Santa for short. In theory, the Mamma Santissima had a very exclusive membership: no more than twenty-four chief cudgels were to be admitted.

Becoming a

santista

involved a new ritual, an upmarket variant of the ’ndrangheta’s existing initiation rites. It also entitled the bearer of this new flower to certain privileges, the most important being the right to join the secret and deviant Masonic brotherhoods that were springing up in 1970s Italy.

The most notorious of the new Masonic groups was Propaganda 2 or P2, a conspiracy of corruption and right-wing subversion that reached right to the heart of the Italian establishment. When, in March 1981, a (probably incomplete) P2 membership list of 962 people was found, it included: