Belisarius: The Last Roman General (20 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Procopius gives a different reason for the detachment of Gibamundus. He claims that Gibamundus was to make a wide swing to the left before moving back in and attacking the Byzantines from their flank (Procopius, III.xviii.1). On close inspection this scenario would appear unlikely, since the eastern road was too far from Ad Decimum – according to Procopius, Gibamundus was travelling northwards forty

stades

(approximately 4½ miles) away from the battlefield. Any troops sent on this route would have little chance of taking part in the battle, since the intervening terrain was hilly and would slow down their movement accordingly. If the troops under Gibamundus were to attack the Byzantines in the manner described by Procopius, they would have stayed with the main force until nearer to Ad Decimum before moving a short way into the

hills. With only a short distance to travel, they would then have been in an ideal position to fall upon the undefended Byzantine flank.

Gelimer’s plan was relatively simple and only depended upon timing. In contrast, at no point did Belisarius want to fight a battle on that day. He still had no clear idea concerning the Vandal’s strength or army composition. What he wanted was information which he could use in order to plan a battle for the following day at the earliest.

The Battle of Ad Decimum

Although usually described as a single battle, the action was actually fought in four distinct and separate phases, all either out of line of sight of each other or at different times.

Opening Moves

Following Gelimer’s instructions, on the early morning of the fourth day after the invasion Ammatus (Gelimer’s brother) ordered his men to follow him to the pass whilst he himself went ahead to scout the area and decide upon deployment.

As the Vandals marshalled their forces and marched towards Ad Decimum, Belisarius was nearing the valley. Around four miles from Ad Decimum, the Byzantines came upon a natural position which was an ideal place to act as a camp. Setting the infantry to fortify the place, and leaving the baggage and Antonina in relative safety, Belisarius led the remainder of his cavalry out to meet the Vandals. With John and his 300 men still scouting ahead and with the Huns still guarding his left flank, Belisarius set forth on the afternoon of the fourth day since their arrival in Africa. His plan was to locate the enemy and assess the strength and the composition of their army, before retiring to the safety of the newly-built camp and deciding upon a strategy for the ensuing battle. Accordingly, he sent the

foederati

under Solomon (Dorotheus having died in Sicily) ahead to contact John and try to locate the Vandal forces. He was unaware that John had already made contact and that the Battle of Ad Decimum had begun.

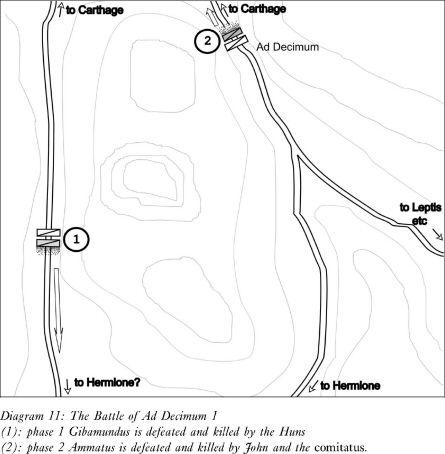

Phase I: The Defeat of Gibamundus

According to Procopius, two engagements occurred at approximately the same time. At around noon, Gelimer’s nephew Gibamundus and his 2,000 men encountered the Huns as they travelled along the third road, close to Pedion Halon, forty

stades

(around 4½ miles) from Ad Decimum. Although outnumbering the Huns by odds of over three to one, the Vandals stopped when faced by a single Hun who rode ahead of his own forces and faced them alone. It is unknown why they stopped: possibly due to fear of a trap, possibly in amazement at the courage of the lone Hun, or possibly due to their surprise at finding enemy troops so far from Ad Decimum. Procopius chooses to claim that they were afraid due to the Huns’ reputation as fierce warriors. Whatever the actual reason, their failure to act put heart into the Huns and they attacked the Vandals at full speed. Without attempting to resist, Gibamundus was killed and his men routed and completely destroyed (Procopius,

Wars,

III.xviii. 18–20).

Phase II: The Defeat of Ammatus

Meanwhile, Ammatus had made a mistake that would prove extremely costly. Instead of gathering a large force and advancing towards Ad Decimum

en masse,

he had gone ahead with only a few troops to assess the proposed battlefield. The rest of his forces followed in small groups of no more than thirty men, stretching back in a long line towards Carthage.

Ammatus reached Ad Decimum around noon, at roughly the same time as Gibamundus was being defeated and killed. Unfortunately for him, he

encountered John and his 300

bucellarii.

Despite killing twelve of the

bucellarii,

Ammatus was himself killed and the remnants of his small force fled back down the road towards Carthage, with John and the

bucellarii

in hot pursuit.

Unable to concentrate their forces and mount a viable defence, the small groups of Vandals that the pursuing Byzantines encountered marching towards Ad Decimum abruptly turned and fled. The whole action quickly assumed a sort of domino effect. The trickle became a flood, with all of Ammatus’ forces retreating towards Carthage. John advanced as far as the gates of the city before his men halted their pursuit. The road back to Ad Decimum was now littered with the bodies of dead and dying Vandals; Procopius stated that the carnage resembled a battle fought by 20,000 assailants rather than 300 (Proc,

Wars,

xviii, 11). The victors slowly began to drift back along the road, looting the bodies of the Vandal dead as they went.

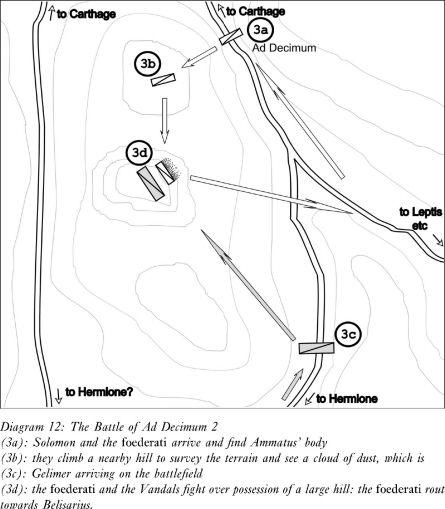

Phase III: The Arrival of Gelimer

Meanwhile, the Byzantine

foederati

under Solomon – moving in advance of Belisarius – had reached the site of the initial fighting between John and Ammatus and had found the bodies of the troops who had died, including that of Ammatus himself. After questioning local inhabitants – presumably friendly thanks to the troops’ excellent behaviour – they were at a loss as to what course to take, so climbed the nearby hills to gain a vantage point over the country thereabouts. Once on higher ground, they noticed a cloud of dust approaching from the south, following the line of the second road; it was Gelimer and the main Vandal force. The leaders of

the foederati

immediately sent messengers to Belisarius, urging him to march as quickly as possible to their assistance. They now argued over whether to retire or to attack the Vandals. However the decision was to be academic. In between the armies was a large hill, the highest in the area. Ideal as a place to establish a camp, with views over all of the surrounding area, individuals in both armies recognised its importance and began to fight to gain possession of the hill.

The Vandals reached the summit first and then, due to the advantage of being uphill as well as having superior numbers, their attack routed the

foederati.

Fleeing in panic, the

foederati

attempted to reach Belisarius and his reinforcements. They retreated until they reached a position held by Uliaris, the commander of Belisarius’ personal guard, along with 800 of his men. The

foederati

expected the guardsmen to join with them and face any further attacks, but they now received a shock: upon hearing the news of the defeat, the Guard broke and fled down the road towards Belisarius and safety.

When the fleeing troops reached Belisarius, they halted. He ordered them to reform their ranks ready for battle and then reprimanded them for their flight. Afterwards, he listened to their reports. Realising that Gelimer had halted and that a large number of Vandals had already been defeated, he believed that he outnumbered the remaining Vandal forces at Ad Decimum. With the knowledge that he had an opportunity to strike a heavy blow at the Vandals; he ordered the troops to march at full speed towards Ad Decimum.

In the meantime, Gelimer himself had a choice to make. According to Procopius, he could have either immediately pursued

the foederati

or moved on to Carthage. Either choice would have been a disaster for the Byzantines. Pursuit would have caught Belisarius unawares and Procopius believes that the Byzantines would have been overrun and completely defeated (Proc,

Wars,

III.xix.25–27). A move towards Carthage would have encountered John and his 300 men, now busily engaged in looting the bodies of dead Vandals. The Vandals would easily have been able to kill them all. In addition, Gelimer

would have been able to capture or defeat the Byzantine fleet, which had ignored its orders and advanced to within reach of the Vandal fleet in Carthage (Proc,

Wars,

III.xix.27–28). Instead, Gelimer descended from the hills at walking pace and so came upon the body of his brother Ammatus. Procopius asserts that Gelimer now began mourning for his brother and arranging for his burial, while his troops aimlessly milled around in the confined space.

The assessment is at fault. Obviously, Gelimer would want to take care of his brother’s body. Yet, unlike Belisarius and Procopius, Gelimer was ignorant of the course of events. The nearby inhabitants had chosen their sides and so did not inform Gelimer of the nature of his brother’s death. Expecting to meet his brother, instead he had found the body of Ammatus alongside those of only a few Vandals and a handful of Byzantines. He would have been at a loss to understand what had happened. Gelimer could not have foreseen that the armed forces from Carthage would be defeated by only 300 men. It would be natural to assume that the Byzantines had advanced faster than expected and either the Vandal forces had immediately fled when confronted with superior numbers, or Ammatus had ordered a retreat, himself dying as part of the rearguard. Gelimer therefore believed that the main body of the Byzantines had already passed and the troops that he had defeated had been the Byzantine rearguard. The main Byzantine force would by now be approaching Carthage.

With these conclusions, one option open to him was to advance immediately and try to attack the Byzantines from the rear in the open space around Carthage. On the clear ground he would quickly be seen and so lose the advantage of surprise. Furthermore, if he did not know already, he would guess that the enemy outnumbered his available forces. Such an attack was not a realistic option. The alternative was to wait until nightfall and send messengers into the town to gain a clearer understanding of what had happened. Then he could decide what to do; either retreat until Tzazon returned from Sardinia or mount an attack in conjunction with the forces remaining in the city. This is a more likely explanation for his delay at this vital moment in the battle. As he was arranging matters, asking for advice and deciding upon his options, disaster struck.

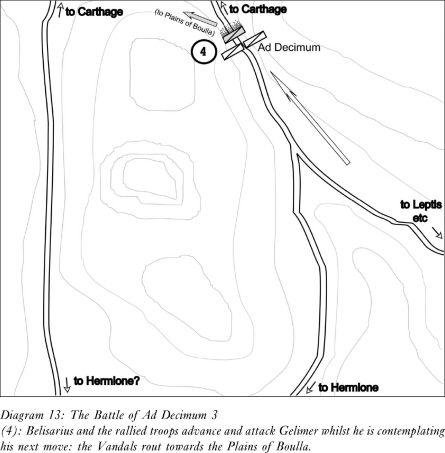

Phase IV: The Arrival of Belisarius and Defeat of Gelimer

At this point Belisarius arrived with his organised troops and swiftly attacked the disordered Vandals from an unexpected direction. Unable to withstand the assault, the Vandals fled, but not in the direction of Carthage. They were still unsure of events and it was probable that there was a substantial Byzantine force on the road to Carthage that could trap them. Instead, they fled off-road towards the relative safety of the Plains of Boulla and the road leading to Numidia. Gelimer had recently made alliances with some of the Moorish tribes in the area, so his decision was valid. This was to be a costly, though understandable, mistake. Although there was no way he could have known, his forces would easily have brushed aside John’s 300 men, who were scattered and intent on gathering plunder, and so have reinforced the garrison at Carthage.